Q&A Special: Musician Lee Hazlewood | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Musician Lee Hazlewood

Q&A Special: Musician Lee Hazlewood

His boots were made for walking: exclusive archival chat with the late great songwriter

Forty-five years ago today, Nancy Sinatra’s risqué “These Boots Are Made For Walking” entered the British charts, beginning its rise to Number One. This country-slanted ode to sex and domination, sung by Frank’s daughter, hasn’t had its impact blunted by repeated exposure on nostalgia radio.

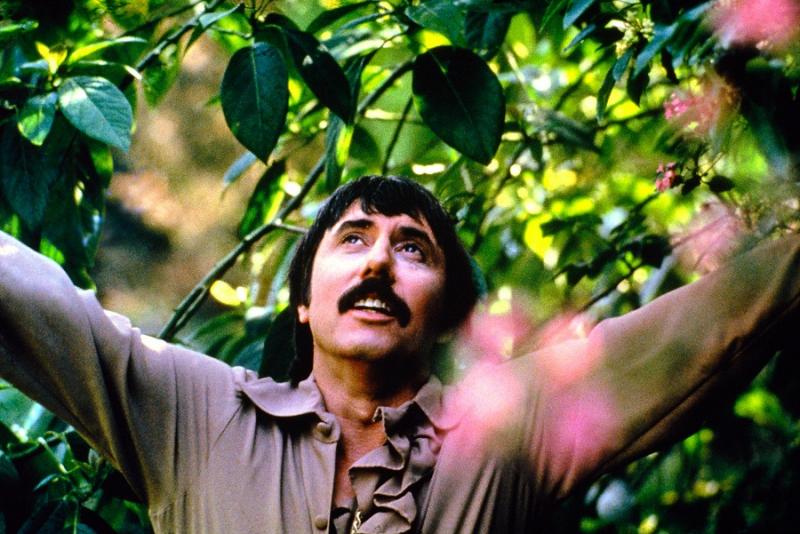

As well as Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, the likes of Phil Spector, country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons, guitar legend Duane Eddy, actress Ann-Margret and Jim Reid of The Jesus and Mary Chain crop up in his career. His records are never less than interesting and usually downright peculiar. He died in 2007. My career-spanning interviews with him – conducted in 1999 – have never previously been fully published.

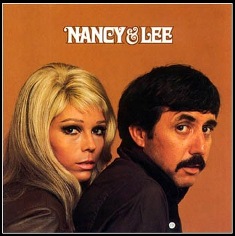

Until 1995 Lee Hazlewood was a slippery, semi-invisible figure, best known for his work with Nancy Sinatra. Their 1968 duet “Some Velvet Morning” – covered by Lydia Lunch and Roland Howard, as well as Primal Scream and Kate Moss – was stranger than “These Boots Are Made For Walking”, way stranger than most psychedelia of the period. Veering between barely cloaked smut – “Some velvet morning when I’m straight/ I’m going to open up your gate” – and a parody of the flower-power concerns of the day – “Flowers growing on a hill/ Dragon flies and daffodils/ Learn from us very much/ Look at us but do not touch/ Phaedra is my name” - the discrepancy between Hazlewood’s gravel and Sinatra’s detached child-like intonation is disorientating.

Watch Lee Hazlewood and Nancy Sinatra sing "Some Velvet Morning"

My interviews were conducted in the weeks after his live show at London’s Festival Hall as part of Nick Cave’s Meltdown Festival. He had never been interviewed at length before, so I became the test case. Despite a vast back catalogue and the fact that he had navigated his way through the mainstream, he’d remained mysterious – a marked contrast to his profile from the Fifties to the Seventies. Despite his cultivated irascibility, he loved to talk.

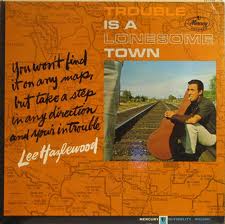

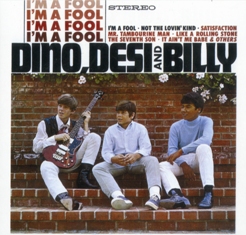

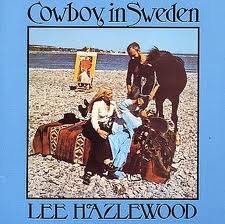

And there was a lot to talk about. In 1952, after serving 18 months in Korea, Hazlewood studied at the Spears Broadcasting School in LA. He’d begun writing songs in 1953 and then, in 1955, spent a year as a country DJ in Coolidge, Arizona. Duane Eddy, of the twangy intros, played regularly on the show. Hazlewood’s production of Sanford Clark’s “The Fool” hit the US Top 10 in 1956. Moving to LA, he steered Duane Eddy chartwards, ran a label with Spector-associate Lester Sill and released Spector’s Paris Sisters’ single “I Love How You Love Me”. Every trend became grist – folk with The Shacklefords; surf with Al Casey. His first solo album was 1963’s idiosyncratic Trouble is a Lonesome Town – each track was preceded by a spoken-word introduction telling the story of the characters living in the fictional town of Trouble.At Frank Sinatra’s Reprise Records in 1965, he wrote for Dean Martin, produced Martin’s son’s band Dino, Desi and Billy and began his partnership with the boss’s daughter Nancy. The solo releases continued and his own label, LHI (Lee Hazlewood International), issued country-rock pioneer Parsons’ debut with The International Submarine Band. Then he drifted off, moving to London, Paris and Sweden, where he released a string of bizarre albums – the most well known of which is Cowboy in Sweden – and made countless Swedish TV specials. By the Nineties he’d moved to Spain. One of his last musical collaborations was with the Icelandic band Amiina. Asked why he moved around, I was told, “So people like you can’t find me.”

He had resurfaced in 1995 on an American tour with Nancy Sinatra. Sonic Youth’s Steve Shelley began reissuing his albums while SY’s Thurston Moore dubbed Hazlewood’s music “country exotica”. A new album Farmisht, Flatulence, Origami Arf!!! and Me soon followed, along with solo shows and 2006’s Eddie Izzard-referencing Cake or Death album. He died aged 78 on 4 August, 2007 from renal cancer.

KIERON TYLER: Would you consider yourself a musician?

LEE HAZLEWOOD: I’m not a musician, I never was a musician and I don’t play anything. I hold a guitar and write songs, but on the back of my old albums I stated I wasn’t a musician, my guitar playing had increased piano sales about 10 per cent in America. All of my musician friends would agree.

How would that affect you when you’re producing records?

I’m not a musician, but I do know music and I do know what I want and I do know what’s best for the artist and what complements the artist, and if you don’t learn that you’re not much of a producer. Arrangers don’t seem to know that, because I tear up arrangements. Arrangers used to hate me - “I wrote this beautiful string line,” and I’d say, “It gets in my singer’s way, it’s out.”

Do you read music?

More than I do the paper.

What sort of music did you play on your Fifties radio shows?

Little Willie John, Howlin' Wolf, and the owner would get mad, but the ratings went up, from 15 to Number One. He said, “I hate your music but I love your ratings.” I was just a smart-ass kid who didn’t want to play Perry Como and Bing Crosby.

What was your reaction to the arrival of Elvis?

A local peace cowboy, a singer, brought me a copy of the first Elvis back to Phoenix and said, “Do you like this kind of music? This old boy's white.” I said, “I don’t care.” I’m playing music on a country station for about four months, and I didn’t know country music real well, but I got books and read about it real fast and I sounded enough like a country disc jockey. I knew the song from before, a Crudup song. Then I got a lot of my callers [accent], “Why are you playing that N's music on the good ol’ cowboy station?” I said, “He’s not, he happens to be a white boy from Memphis, and who cares if he can sing like that.” I was the only one playing it on the station, there was this wonderful lady at the big record store in Phoenix, and she called me up, I’d been playing it for about three days. “Alright Lee, this is Mavis, you been playing a record by Eavis [sic] Presley, what’s the label? I’ll have to order some, you do that all the time, you find these weird people.” About two, three weeks go by, and she says “You know what, you might be in the wrong business.” So I got a small reputation for finding a hit, but they happened to be things I like, mostly blues, black artists. In my own small way I broke some records in Phoenix.You’d been in the army before that?

Let’s see, June of 1950 I was in the army and I went to Korea and I was there for 18 months. That’s all we talk about the army. I never was an armed-forces DJ. I went to radio school afterwards to correct some of my Southern drawl, that was on GI bill. About two years [there]. I got a job the day I finished. I was in Coolidge, Arizona, about an hour outside Phoenix. One [radio station] in Coolidge for a year, one in Phoenix for about eight months, then they changed their format and then I went over to another one in Phoenix for two and a half, almost three years. I was at university before that [the army].

What did you study?

Pre-med. I already finished my pre-med, and was already accepted for SMU [Southern Methodist University] Medical School and the Korean War came along.

What made you start you first label Viv Records?

For some of the local artists that we thought were good enough to be on major labels, three or four of them I think ended up on major labels. It worked out so good, because we’d press 1000 and we’d sell 1000. That’d just about get the money of our sessions back, so we could make another record of somebody else. Most of all of the things on Viv were covered by Decca, Columbia, and then they’d call up and try and steal the publishing from us, and I’d say, “No, I don’t think so.” We had about six or eight country music distributors, we took care of the South.

I ran out of money and gave the back [the B-side] of the record to the guy who owned the studio, because I expected we’d sell another 1000 or so. But we ended up selling 800,000. That was “The Fool” by Sanford Clark. Some disc jockey called me from somewhere in Ohio, and he said, “You got a hit.” I said, “I didn’t know they played country music in Ohio,” and he said, “It’s not country, it’s pop.” I said, “I knew that” – I didn’t know that. The orders came in from everywhere, we had to lease it out to Dot.

What was the origin of the Duane Eddy guitar sound?

It was from Eddie Duchin back in the Forties playing the melody on the low keys of piano. It was low on the piano, it made it low on the guitar.

How did you hook up with Lester Sill?

I was doing some work for Dot which I hated, then I was trying to quit every week. I met Lester in that time when Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller were moving to New York, and Lester came to me and said, “I really like the way you’re writing, and I would like work with you. I’ll give you the same deal I had with Leiber and Stoller; they paid me 15 per cent.” I said that I wouldn’t want a partner that I paid less than 50 per cent, and after Lester got off the floor we started our partnership. I think we put up about $200 each, and made the first Duane Eddy record.

Phil Spector released stuff under the Spectors Three name on your label Trey.

He did The Paris Sisters’ “I Love How You Love Me” which was a pretty good-size hit. When he did it, Lester took it around to everybody to try and lease it and nobody liked it. We released it independently, and had a hit, but the follow up… Phil was interested in other things. But it was good for Phil.

Listen to The Paris Sisters’ “I Love How You Love Me”

What made you step out of the back room to make records under your own name?

There was a guy that ran the music department at [film company] AIP, and he said, “We have this really weird movie Lee, I want you to come and see it.” I said, “I don’t really like AIP movies, they’re cheapies.” “Well you’ll see this one, it’s got Debra Paget in it.” I said, “I’ll be over this afternoon” - Deborah Paget was pretty hot in those days. “It’s called The Girl on Death Row, could you write something for it?” “I’m going to Phoenix, I’ll cut you a demo, and you can get someone to do it.” I cut him the demo and they liked it, and about two days later he called and said it was a really good song. Then a couple of days after that he rang and said he’d played it to Arkoff [Sam – AIP’s boss], and he wanted to use the demo in the film. So that was the start of my illustrious singing career – except about three weeks before it was released Arkoff changed the title [of the film] to Why Must I Die?

You dipped your toe into surf music.

I didn’t care anything about surfing music, but I wrote “Surfin’ Hootenany” for Duane. But I think we had some little problems. So I said to [session guitarist and friend] Al Casey, “Do you want to record this song?” and he said it was really a dumb song. So we got the girls, Darlene Love and all of them that sang for Spector, that sang for everybody. Six great background singers that could make any corny song sound like it was Ray Charles doing it. I didn’t take it seriously, but I thought it was a good gimmick record: we get together, get our guitars and all sing together and play out of tune. “Surfin’ Hootenany” was a joke, but a good joke.

Listen to Al Casey's “Surfin’ Hootenany”

The next thing along was your solo LP Trouble is a Lonesome Town. That was a demo, because I thought I had a good idea; it was a concept album, but I didn’t know it was a concept album. I wrote a complete story of a make-believe town, and I took it to everyone I knew, and they all turned it down. Jack Tracy, the West Coast head of Mercury, a good friend, I said [to him], “Here’s something for you to listen to, but take it home, I don’t want to stand in front of you.” I got home, ready to eat my meal with my then-wife and kids, and the phone rang and it was Jack and he said, “I just played this for my wife, and Lee, this is the sharpest, brightest thing I’ve heard out of you or anyone else. Is it finished?” “As far as I’m concerned it’s a good demo,” and he said, “I think it goes out like this.” It sold a few, then I released it again later on LHI.

That was a demo, because I thought I had a good idea; it was a concept album, but I didn’t know it was a concept album. I wrote a complete story of a make-believe town, and I took it to everyone I knew, and they all turned it down. Jack Tracy, the West Coast head of Mercury, a good friend, I said [to him], “Here’s something for you to listen to, but take it home, I don’t want to stand in front of you.” I got home, ready to eat my meal with my then-wife and kids, and the phone rang and it was Jack and he said, “I just played this for my wife, and Lee, this is the sharpest, brightest thing I’ve heard out of you or anyone else. Is it finished?” “As far as I’m concerned it’s a good demo,” and he said, “I think it goes out like this.” It sold a few, then I released it again later on LHI.

After that you were on Reprise.

That was the result of [label boss] Mo Austin loving Trouble… I said it was part of a trilogy and Mo, he said, “Why don’t you do something like that for us, Lee? They [people in the business] thought it ought to be a television show, what a great idea for a television show," blah blah, blah. It’s all bullshit. Of course they wanted to bring in a bunch of idiot hack writers from New York. None of that stuff worked out, but oh boy, a lot of heavy negotiation went on. I always called Mo’s wife “the nurse”, because she always gave me aspirins at record conventions, because I couldn’t stand record conventions. There would always be some disc jockey. “I really like this one,” and I’d go, “I don’t give a fuck, I don’t care what you like.” Then Reprise almost insisted I didn’t go to those. I don’t need a bunch of critics or goddamn disc jockeys because I was one.

What was your reaction to the British Invasion?

I just stopped making records for about a year and a half, I just retired. Why make ‘em? Every lousy goddamn British group in the world was in the charts in America.

You produced Dino, Desi and Billy for Reprise. I did Dino, Desi and Billy as a favour to [producer] Jimmy Bowen, knowing that working with two 12-year-olds and a 13-year-old is gonna make you want to slit your wrists. These kids made one appearance on The Dean Martin Show, and they got 30 tons of mail, and I said that I really don’t want to do three million albums on them in that year I had them and I had a royalty that was better than theirs, and still after all that profit margin I quit at the end of the first year. They were hell to work with. They later apologised to me when they got to be young men.

I did Dino, Desi and Billy as a favour to [producer] Jimmy Bowen, knowing that working with two 12-year-olds and a 13-year-old is gonna make you want to slit your wrists. These kids made one appearance on The Dean Martin Show, and they got 30 tons of mail, and I said that I really don’t want to do three million albums on them in that year I had them and I had a royalty that was better than theirs, and still after all that profit margin I quit at the end of the first year. They were hell to work with. They later apologised to me when they got to be young men.

Watch Dino, Desi and Billy perform "I'm a Fool"

How did you end up with Nancy Sinatra?

That was Jimmy Bowen, my next-door neighbour, asking me would I record her, and I said I’m tired of second-generation artists and he kept on and on and on, and he said, "Lee, will you meet her?" and I said, “I don’t care.” So I went over to her house, and it’s hard to say no to Sinatras; they’re just good at what they do. They had several of my friends over there, and strategically placed bottles of Chivas around the room. Mama, that’s what I always called Nancy senior, had made some Italian food with a slight country taste to it, the only Italian food I ever had in my life that I liked, and Lee had a scotch or two, and you can guess who walked in the door, introduced himself and said, “I’m glad you two are working together”. So I said I’ll do one. Even though we only sold about 60,000 with “So Long Babe”, I thought this song I had written for her would sell at least three times that. A beautiful song called “The City Never Sleeps at Night”. She learned the new song, and we’re through with it, just sitting around and we started singing some suggestive Texas songs for fun and she’s just breaking up cause she’s never heard any of this stuff before, and I said, “I’ve got the greatest Texas love song you’ve ever heard in your life, I’ve only got two verses,” and I sang her “Boots”. She said, “I want to record it,” and I said, “You can’t because it’s dirty.” On the way to the date Nancy called me in the car, believe it or not I had a phone in the car, and I said, “I never did the other verse to the song!” So from my house in North Hollywood to the studio is about, on a good afternoon, seven minutes, or eight minutes tops – that’s where the middle verse to “Boots” was written. When I got there I wrote it all out real fast and gave it to her.

Even though we only sold about 60,000 with “So Long Babe”, I thought this song I had written for her would sell at least three times that. A beautiful song called “The City Never Sleeps at Night”. She learned the new song, and we’re through with it, just sitting around and we started singing some suggestive Texas songs for fun and she’s just breaking up cause she’s never heard any of this stuff before, and I said, “I’ve got the greatest Texas love song you’ve ever heard in your life, I’ve only got two verses,” and I sang her “Boots”. She said, “I want to record it,” and I said, “You can’t because it’s dirty.” On the way to the date Nancy called me in the car, believe it or not I had a phone in the car, and I said, “I never did the other verse to the song!” So from my house in North Hollywood to the studio is about, on a good afternoon, seven minutes, or eight minutes tops – that’s where the middle verse to “Boots” was written. When I got there I wrote it all out real fast and gave it to her.

Did it seem like a weird follow-up to the folk rock of “So Long Babe”?

It was weird, weird, weird anyway. The musicians would go, “What is it - a four-chord cowboy song?” It’s a four-cowboy jazz song. I always had the riff.

Watch Nancy Sinatra perform "These Boots Are Made For Walking"

The Nancy and Lee LP contains some extraordinary material, like “Some Velvet Morning”. I wanted it to go into the waltz. I had some personal problems with people telling me, “I really like the song you wrote Lee, you can really dance to it." I don’t like people dancing to my music. I was being very contrary. The next thing I sat down to write happened to be that song and I go, dance to this sons of bitches. Phaedra is of course a Greek goddess, and she had a sad ending and beginning. She became the most interesting to me in the little mythology thing I like to do. What started it to me was, every night I read to my children the Greek mythology stories - I thought they were a lot better than all those fairy tales that came from Germany that had killings and knifings. So that’s where my interest was, and there was only about seven lines about Phaedra – she had a sad middle, a sad end, and by the time she was 17 she was gone, she was a sad-assed broad. So bless her heart, she deserves some notoriety, so I’ll put her in a song. The meaning is that she's the saddest of all Greek goddesses, so little is known about her except that she was so miserable, but what a great lady.

I wanted it to go into the waltz. I had some personal problems with people telling me, “I really like the song you wrote Lee, you can really dance to it." I don’t like people dancing to my music. I was being very contrary. The next thing I sat down to write happened to be that song and I go, dance to this sons of bitches. Phaedra is of course a Greek goddess, and she had a sad ending and beginning. She became the most interesting to me in the little mythology thing I like to do. What started it to me was, every night I read to my children the Greek mythology stories - I thought they were a lot better than all those fairy tales that came from Germany that had killings and knifings. So that’s where my interest was, and there was only about seven lines about Phaedra – she had a sad middle, a sad end, and by the time she was 17 she was gone, she was a sad-assed broad. So bless her heart, she deserves some notoriety, so I’ll put her in a song. The meaning is that she's the saddest of all Greek goddesses, so little is known about her except that she was so miserable, but what a great lady.

It’s an odd LP, because on one hand you’ve got songs like that and, say, a cover of The Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feeling”.

Nancy wanted to do that.

I’m not sure about that.

You’re not sure about it, I was less sure about it and Nancy, to make me very happy, she brought [Righteous Brother] Bill Medley down to the session when I’m doing the overdubbing. That’s really wonderful, huh?

Was that a good idea?

Oh, is that the most lousy fucking idea you ever heard in your life? Bill goes, “I kinda like it Lee, its kinda different.” I said, “It really is Bill.” After they left I redid it.

But your songs on the LP, “Sand” or “Summer Wine”, have that brooding atmosphere…

Aren’t they swell?

They are swell, and quite unlike anything else...

They’re all covered up with all kinds of meanings. Everybody used to come up and go, “What does this mean?” and I'd go, “What does this mean to you?” “I think its de de de,” and I say, “You got it exactly right.” That way everybody gets a chance to know exactly what the song means - a sort of democracy for listeners. They’d say “in ‘Some Velvet Morning’ does this mean…?” and I'd tell them, “Damn, you got it right away." "Thank you. I was telling my wife that last night. I thought that meant that.” Having participated in this little bit of theatre they knew the meaning, and God knows – I maybe didn’t.

Was that a subversive or contentious move, putting songs like that on an LP by a Sinatra?

It had nothing to do with Sinatra. Her name could have been Nancy Brown. They’ve lasted haven’t they? The ones that I wrote particularly, the others I put on as favours for friends. I doesn’t bother me [cover versions] because that’s their interpretation.

You were still making solo records.

The record companies used to call you and ask you to do “writer’s albums”, they were called in those days. If you happened to have a hit or two at that time you’d throw this in. I consider them good, expensive demos paid for by major record companies. It saved me from taking stuff around to other people, they’d just get the next LP and record some of it.

Who chose “Something Stupid”?

Frank Sinatra, he found it. It took him one day to find it, and three days to find me. He played it for me and he says, “You’ve been wanting me to do something with the kid,” and I said "I like it." Frank wanted me to produce it, but I said, “No I can’t, Jimmy Bowen produces you, so we’ll both have to do it.” It wasn’t very difficult, I didn’t pay attention to Jimmy and he didn’t pay attention to me. We brought in our rhythm section - Hal Blaine, Don Randi, Al Casey, Donnie Owens and on and on – and got rid of his [Frank’s] and we were the last hour of the Jobim album that he was doing. Nobody mentioned a follow up.

Listen to Frank and Nancy Sinatra's "Something Stupid"

How successful was LHI records?

Not at all. I did run it but I had way too much to do. I think a lot of the stuff was produced and I just bought it.

How did you end up with Gram Parsons' International Submarine Band?

Suzi Jane Hokem [who co-ran the label with him] found them; they weren’t lost, but she found them. They were just on my label.

What about Ann-Margret?

Her managers called me one time and asked me to do something with her. We met, got along alright and we put out an album that wasn’t too successful.

You mention money quite a lot, is it a great motivator for you?

Absolutely, you’re damn right it is. Anybody who goes into this business and doesn’t believe that, there’s something wrong with them. If you don’t go into the music business to make money there’s something wrong, ‘cause it’s there to make money. I was very hungry from the beginning, and it was a lot easier to do than other things I’ve had to do in life.

When did you move to Sweden?

I started coming in 1969, moved in the Seventies. Sweden has left me alone, and consequently I love them for that.

Watch an extract from Swedish TV's Cowboy in Sweden Lee Hazlewood spectacular

Were you bothered that records released in Sweden didn’t come out in America?

No, not at all, I didn’t care about it. I cared about the records, but I cared about them for Europe, not America. My records never did any good in America anyway. Most of the stuff was written around TV shows, not necessarily to be in them. I ended up being in a lot of them, but I didn’t plan on that. I just wanted to write them.

No, not at all, I didn’t care about it. I cared about the records, but I cared about them for Europe, not America. My records never did any good in America anyway. Most of the stuff was written around TV shows, not necessarily to be in them. I ended up being in a lot of them, but I didn’t plan on that. I just wanted to write them.

Requiem For an Almost Lady is a very tough LP.

Yeah it is. There’s a lady or two who think it’s about them, but it’s not. It’s written about a lot of people.

What was your reaction to the 1973 New Musical Express single-word review of Poet, Fool or Bum? (by Charles Shaar Murray, who wrote “Bum”)

I’d love to meet him some time. That was one of my good albums, and he’s absolute living proof that all horse’s asses in the world are not on horses. I don’t care about reviews, but clever things don’t astound me at all.

What do you make of your sound-alikes?

I feel kinda sorry for them. They could have picked somebody else better to sound like. If they want to, that’s fine. They’re all young people, and I enjoy young people.

What happened to you working with The Jesus and Mary Chain?

Their manager screwed that up. I was all ready to work with them. The boys and I had it all set in our minds what we wanted to do. I like the boys fine, I was going to do a couple of things on their album.

How come you toured with Nancy Sinatra in 1995?

I was living in Spain, and she called me and asked me to do it. Every year I move so you people can’t find me. Also I like to live places where nobody has heard of me. I’m not wanted, there’s no outstanding contracts on me.

You must travel light.

Very light, I lease everything. When the time comes to go, you go.

It seems that you have become a genre rather than an artist.

I’m glad you said it and I didn’t.

What sort of music do you listen to at home?

I listen to talk radio a lot, and I listen to an alternative music station a couple of hours a day just to see what we would have called in the old days the "garage bands" are doing. I have a 20-year-old daughter who’s more a Sonic Youth fiend than I am.

What favourites do you have from your career?

“If It’s Monday Morning” is one of my favourites that I like to do. “Dolly Parton’s Guitar” is one of my least favourites, but nobody understands that song until you explain it to them. Now some of the songs have value, they weren’t noticed, they weren’t played, and now they are. Not the hits, I’m talking about the obscure ones; it takes a while sometimes. The thing that interests me is to look out in the audience and see the age of the people that’s out there. That’s very interesting, it makes me happy. Not very much makes me happy, but that makes me happy.

Watch the video for Lee Hazlewood and Amiina's "Hilli"

- Find Lee Hazlewood on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Viagra Boys - Viagr Aboys

Louder, weirder and all the way in

Album: Viagra Boys - Viagr Aboys

Louder, weirder and all the way in

Music Reissues Weekly: 1001 Est Crémazie

Privately pressed Canadian jazz album resurfaces for its 50th anniversary

Music Reissues Weekly: 1001 Est Crémazie

Privately pressed Canadian jazz album resurfaces for its 50th anniversary

Album: Maria Somerville - Luster

Irish musical impressionist embraces shoegazing

Album: Maria Somerville - Luster

Irish musical impressionist embraces shoegazing

Album: Ronny Graupe's Szelest - Newfoundland Tristesse

A deep, subtle and constantly engaging album

Album: Ronny Graupe's Szelest - Newfoundland Tristesse

A deep, subtle and constantly engaging album

Album: Gigspanner Big Band - Turnstone

Third album from British folk’s biggest big band

Album: Gigspanner Big Band - Turnstone

Third album from British folk’s biggest big band

Album: Mark Morton - Without the Pain

Second solo album from Lamb of God guitarist lays down hefty southern boogie

Album: Mark Morton - Without the Pain

Second solo album from Lamb of God guitarist lays down hefty southern boogie

Manic Street Preachers, Barrowland, Glasgow review - elder statesmen deliver melody and sing-a-longs

The trio ran through new songs, obscure oldies and big hits in a career spanning set

Manic Street Preachers, Barrowland, Glasgow review - elder statesmen deliver melody and sing-a-longs

The trio ran through new songs, obscure oldies and big hits in a career spanning set

Album: Rhiannon Giddens & Justin Robinson - What Did the Blackbird Say to the Crow

Finger-picking good

Album: Rhiannon Giddens & Justin Robinson - What Did the Blackbird Say to the Crow

Finger-picking good

Music Reissues Weekly: Motor City Is Burning - A Michigan Anthology 1965-1972

Wide-ranging overview of the US state accommodating Detroit, the ‘rock city’

Music Reissues Weekly: Motor City Is Burning - A Michigan Anthology 1965-1972

Wide-ranging overview of the US state accommodating Detroit, the ‘rock city’

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2025

What Record Store Day exclusives are available this year?

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2025

What Record Store Day exclusives are available this year?

Album: Joe Lovano - Homage

Free-flowing spontaneity

Album: Joe Lovano - Homage

Free-flowing spontaneity

Album: Bon Iver - SABLE ƒABLE

An album of exquisite wonder

Album: Bon Iver - SABLE ƒABLE

An album of exquisite wonder

Comments

...

...

...