I’m stood in the dusk in front of the tomb of Sheikh Hamid al-Nil as the sun sets on Khartoum, reddening in the exhaust-filled air as it deflates over a receding jumble of low-rise blocks spreading down the banks of the Nile and out towards Tuti Island, where the waters of the Blue and White Nile meet. This is no quaint, picturesque view, though you do feel you're in some ancient theatre of humanity when you land in Khartoum.

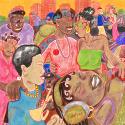

The voice of a Koranic singer billows and froths from the PA and speakers studded around the conical cream-and-green tower of the mosque, and a crowd of several hundred Sufi worshippers circle a square of bare burnt ochre earth where dancers sweep up and down in a line through the middle, while others circle the square or just stand there at the edges, rocking back and forth until - as if they have stepped through some invisible gate - they begin to turn, faster then faster again.

The Sufi dancers are a regular spectacle in Khartoum (see video below). You will find them here every Friday at sunset, just as you can see the Nubian wrestlers grappling at sundown every Sunday. Night comes quickly this far south, the Dog Star high in the sky as I turn from the Sheikh’s tomb towards the burial ground between here and the distant road. Sudani locals flicker by in the deepening gloaming.

Watch the Sufi dancers perform

By now, the jagged voice from the PA has gone silent; behind me, the dervishes swirling in the dust and brazier smoke in front of the Sheikh’s tomb in the hour before sunset have fallen to their knees, facing east. I pick my way along the indented path, careful to avoid the makeshift-looking graves scattered either side of me as haphazardly as the city traffic surges beyond the gates onto the road ahead.

In these Muslim burial grounds, lorry tyres are put in place of gravestones, and dusty piles of gravel are heaped in small, irregular mounds amid clumps of wild pale long grasses. Down to earth doesn’t begin to describe this land of the dead. The land of the living is marked by the pails of water left on the street outside its gates for anyone to slake their thirst. It’s a simple, effective charity for a people who have seen and been through much. Their country’s President, who forcibly took office in 1989 and still can’t see the exit signs, may have dragged Sudan to the status of pariah and an economic basket case to boot, but along with the crumbling infrastructure or the goat herders on the airport road, you can’t fail to miss the high level of civilisation, interaction and discourse that passes up and down its sun-dried streets each day.

In these Muslim burial grounds, lorry tyres are put in place of gravestones, and dusty piles of gravel are heaped in small, irregular mounds amid clumps of wild pale long grasses. Down to earth doesn’t begin to describe this land of the dead. The land of the living is marked by the pails of water left on the street outside its gates for anyone to slake their thirst. It’s a simple, effective charity for a people who have seen and been through much. Their country’s President, who forcibly took office in 1989 and still can’t see the exit signs, may have dragged Sudan to the status of pariah and an economic basket case to boot, but along with the crumbling infrastructure or the goat herders on the airport road, you can’t fail to miss the high level of civilisation, interaction and discourse that passes up and down its sun-dried streets each day.

I’m in Khartoum with Sam Lee, a young English traditional singer with a fine baritone and a head stuffed with the oldest and richest songs still surviving in Britain, learnt first-hand from the traveller and gypsy singers who have kept them alive and circulating, like antibodies in the national bloodstream, for generation after generation. They are singers with whom he has lived and studied over the past decade. Families such as the Robertsons and Stuarts of Scotland, the Penfolds of Sussex, the Leggs of Devon.

He was musical advisor on the Travellers Got Talent competition that features in Sky’s new series, A Gypsy Life for Me, and as well as a singer with a debut album due in 2012. He runs the BBC Folk Award-winning Magpie's Nest club, a movable feast of folk traditions that ranges from English folk duos to Transylvanian fiddle bands and crops up at venues across London.

Sam Lee and Friends - (his seven-piece band, pictured below) - have been brought here to perform and workshop with local musicians by the British Council in Khartoum. The Council has worked intensively over the last few years on cultural programmes that not only bring British artists from a range of disciplines here, but fosters among local Sudanese the kinds of skills and knowledge necessary to be able to mount and market music events with a mentoring programme and what started in 2009 as WAPI – Words And Pictures.

WAPI was based on the notion that music and art is as much a safety valve for war-damaged Sudan as it is for anyone else in the world, and that intensive, on-the-ground schemes to promote art and music in both North and South Sudan – both became “new” countries in July 2011 – would help foster the values, cultural exchange, development and openness that the British Council represents worldwide.

WAPI was based on the notion that music and art is as much a safety valve for war-damaged Sudan as it is for anyone else in the world, and that intensive, on-the-ground schemes to promote art and music in both North and South Sudan – both became “new” countries in July 2011 – would help foster the values, cultural exchange, development and openness that the British Council represents worldwide.

WAPI was a big success – from the first intimate concerts in the garden of the British Council compound to public gatherings of more than 3,000. Following that came the Creative Coalition, between the British Council and their French, Spanish and German counterparts in the city, and with the newly appointed Minister of Culture, Alsamaweel Khalafala, the fruit of which was to revive Khartoum’s International Festival of Music, started in 1989, and stopped by hard-liners after its ninth edition in 1997. Since that time, says Tilal Salih, a young cultural development officer at the British Council in Khartoum, “there has been no platform, really none, for Sudanese music”.

For the time being, it remains a shaky one. The festival’s generous budget held good until harsh economic realities stepped in. With inflation souring, foreign reserves plummeting and the economy tanking as a result of oil revenues being directed to the newly created South Sudan, the festival budget was stuck at zero. “All the artists from Sudan are doing it for free,” explains Salih. “There is no budget. So the artists need to decide whether they can do it for free or work so they can feed their kids. That is the dynamic here.”

It was the British Council that flew in Sam Lee and Friends with violin, cello, brass, percussion, and what multi-instrumentalist Saul Eisenberg calls “A Pentatonic Tank in E” – a refashioned gas cylinder – to perform with musicians including the mighty singer Omar Ihsas from Darfur, one of the few internationally known Sudanese artists, and one who has continued to perform in Darfur throughout the civil war; and Dr Al-Fateh Hassan, a demon guitarist with a hand of gold and a tone that West African giants such as Orchestra Boabab’s Bartholemy Atisso would love.

It was the British Council that flew in Sam Lee and Friends with violin, cello, brass, percussion, and what multi-instrumentalist Saul Eisenberg calls “A Pentatonic Tank in E” – a refashioned gas cylinder – to perform with musicians including the mighty singer Omar Ihsas from Darfur, one of the few internationally known Sudanese artists, and one who has continued to perform in Darfur throughout the civil war; and Dr Al-Fateh Hassan, a demon guitarist with a hand of gold and a tone that West African giants such as Orchestra Boabab’s Bartholemy Atisso would love.

Rehearsing at the run-down but homely Musicians Union (“Everyone joins, nobody pays,” smiles Salih) and The Traditional House of Arts, a small theatre in downtown Khartoum, the Anglo-Sudanese musical summit tackled Child Ballads such as "George Collins", a chilling tale of a supernaturally seductive woman – a water-sprite, in fact - snaring a doomed young man who meets his death with a poisoned kiss when he leaves her for another. It’s the kind of song that drips with collective archetypes that communicate across cultures as effectively as any mobile network.

With the strings, rhythm section and brass from Dr Al Fateh’s band merging together with their counterparts in Sam Lee’s band, the musicians break the songs down to their separate body parts, and bring them back to ruddy life on stage the following night. Folk traditions are full of such resurrections, and hapless "George Collins" gets a hugely positive reaction from the Sudanese audience – helped in part by Lee’s decision to inveigle a translator to introduce the stories and themes behind the songs.

The three of them improvised a stunning and heartfelt performance of a hare-coursing song that met midway between Sudanese and British folk traditions

The canny curators at the British Council knew what they were doing when they booked a young, contemporary folk group like Sam Lee and Friends. English folk belongs to that wider ocean of song that laps one tradition against another so you barely see the joins, and Lee’s band approach it from a fresh angle that’s inclusive of outside influences and foreign bodies – gas tanks included – which helped the collaboration work some real onstage magic.

But perhaps the most powerful magic came during a break in the garden of The Traditional House of Arts, Lee sat with Ihsas and Dr Manal Eldin, a pharmacist by profession, and a singer with the most clear and beautiful voice, and the three of them improvised a stunning and heartfelt performance of a hare-coursing song that met midway between Sudanese and British folk traditions, with Saul Eisenberg on his gas canister (see video below) and the three singers trading verses in different languages and on the same melody. They'd repeat it on stage the following night, to close the set before Ihsas's own band swept on to deliver an energetic, powerful performance drawn from the folk and country music of his native Darfur.

Watch Sam Lee, Omar Ihsas and Dr Manal Eldin improvising

The following day, Sam Lee and co are roaming separately through the vast Ouderman souk after sunset (pictured below right), the arc lights and naked bulbs ablaze over a warren of stalls of everyday produce – cooking pots, shoes and sandals; seemingly millions of them – caves of garish fabric, of baskets filled with ginger, garlic, figs and dried okra; great pyramids of turmeric, tea and cinnamon; kid goats skinned and forked on a steel hook in front of the butcher stalls; the koranic singer on the communal radio with a voice like folded silk. It’s easy to fall into a kind of spell here. Aside from aid workers, there are few Western visitors, and even fewer who appear on national TV, and it’s easy, too, to be drawn into conversation.

You get a measure of the festival’s impact – it has received widespread television coverage – when Lee is stopped in the middle of the souk, which is the largest in Sudan, by a distinguished-looking Sudanese elder in traditional costume, who berates him sternly for dancing on stage. Such things remain taboo here. “It is very bad,” he is told. Though there were instances of Sudani teens climbing up to throw some shapes – and amazing movers and shakers they proved to be – the younger Sudanese singers, pretty boys with great voices honed by chanting koranic verses, barely moved at all. During the instrumental breaks, they’d stand stock still, tapping a microphone into the palm of their hand, staring into mid-distance as if contemplating breakfast or mortality, or George Collins... It makes for a most peculiar stage tension, as if they’ve been reducted from within. US R&B singers should give it a try.

You get a measure of the festival’s impact – it has received widespread television coverage – when Lee is stopped in the middle of the souk, which is the largest in Sudan, by a distinguished-looking Sudanese elder in traditional costume, who berates him sternly for dancing on stage. Such things remain taboo here. “It is very bad,” he is told. Though there were instances of Sudani teens climbing up to throw some shapes – and amazing movers and shakers they proved to be – the younger Sudanese singers, pretty boys with great voices honed by chanting koranic verses, barely moved at all. During the instrumental breaks, they’d stand stock still, tapping a microphone into the palm of their hand, staring into mid-distance as if contemplating breakfast or mortality, or George Collins... It makes for a most peculiar stage tension, as if they’ve been reducted from within. US R&B singers should give it a try.

Nevertheless, held at a microphone’s length in those young singers’ body tension is a glimpse of how the new Sudan may be able to sing and talk itself open and engage with the outside world instead of swinging its doors shut, once again, and bringing the curtain down on the small freedoms and loosening of strictures the Sudanese in Khartoum, at least, have enjoyed in the last two years - women able to wear trousers without punishment, a burgeoning press allowed larger freedoms, bands and DJs actually able to perform in public without being arrested.

Economics may bite hard in the coming months but there is something in the air, and what the 10th International Festival of Music has done, against heavy odds, is to foster an exchange of cultures, modes, of artistry. And Sam Lee and his band’s performance may have helped, just a little, to fan it to a nationwide audience in Sudan. With another festival planned for next January in Port Sudan, where the temperature sits at a bucolic 26 degrees all year round, and the ambitious mayor has plans to turn it into the Red Sea’s newest tourist resort, Lee and friends are eager to come back and pick up the tempo where they left it, and see if they can encourage a few more dancers.

Add comment