theartsdesk Q&A: Shirley Collins - 'There was no way I could ever sing to be popular' | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Shirley Collins - 'There was no way I could ever sing to be popular'

theartsdesk Q&A: Shirley Collins - 'There was no way I could ever sing to be popular'

Ahead of next week’s Roundhouse concert, the voice of traditional English music reveals some unexpected musical likes and much more

When Shirley Collins appears at The Roundhouse next week, it will be 50 years since she last played there. On 30 May 1969, she and her sister Dolly were on a bill promoting their then label Harvest Records. When she plays there on 31 January, she is the main event.

Lodestar was released 37 years after her last full-length album, 1979’s Shirley & Dolly Collins set For as Many as Will. The – as she puts it – “long layoff” was forced upon her after she developed hysterical dysphonia in the wake of the collapse of her marriage to Fairport Convention’s Ashley Hutchings. The consuming sadness meant she, literally, could not sing.

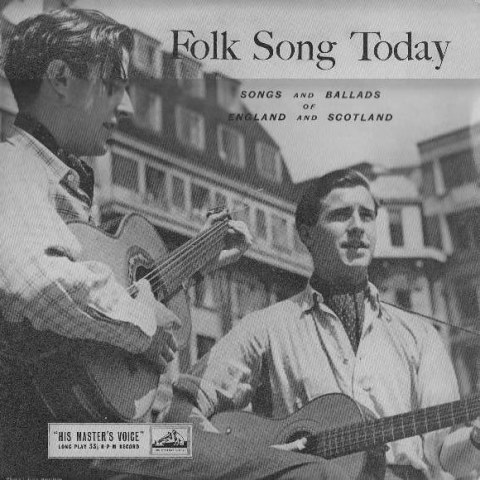

Shirley’s lengthy involvement in the music she loves is stressed by knowing her first appearance on record was in 1955, when she sang “Dabbling in the Dew” on the compilation album Folksong Today. Its liner notes declared “Shirley, who works in a London coffee bar, learnt most of her songs at home in Sussex. She is a young girl with a modern approach to folk music, laying an automatic zither across her knee and pressing buttons to select accompanying chords.” This first recording came after her burning desire to sing impelled her to write a letter to the BBC which resulted in a visit to her family’s Hastings home by local singer and song collector Bob Copper.

Shirley’s lengthy involvement in the music she loves is stressed by knowing her first appearance on record was in 1955, when she sang “Dabbling in the Dew” on the compilation album Folksong Today. Its liner notes declared “Shirley, who works in a London coffee bar, learnt most of her songs at home in Sussex. She is a young girl with a modern approach to folk music, laying an automatic zither across her knee and pressing buttons to select accompanying chords.” This first recording came after her burning desire to sing impelled her to write a letter to the BBC which resulted in a visit to her family’s Hastings home by local singer and song collector Bob Copper.

By the end of the Fifties, she was in a relationship with the American though London-resident folklorist and song collector Alan Lomax. She accompanied him to America on a song collecting expedition which became the subject of her 2004 book America Over the Water. Her fundamental contributions to Lomax’s own 1960 book Folk Songs of North America ensured she was also integral to America’s understanding of its traditional music.

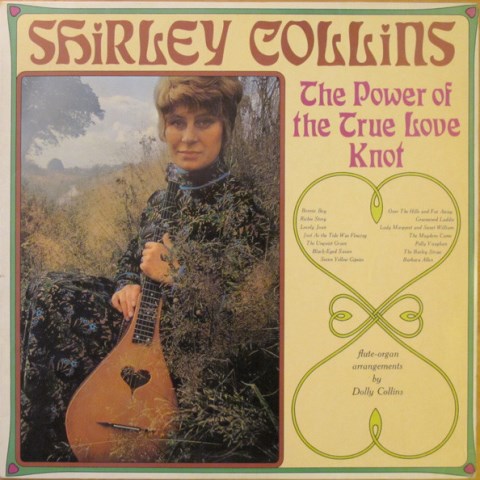

She has issued a string of landmark albums: among them The Sweet Primeroses and The Power of the True Love Knot in 1967; Anthems in Eden in 1969 and Love, Death & the Lady in 1970. Her sister Dolly was never far. In 1970, Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band’s No Roses was released: she and Hutchings formed the Albion Band. In 2007, she was awarded an MBE for services to music.

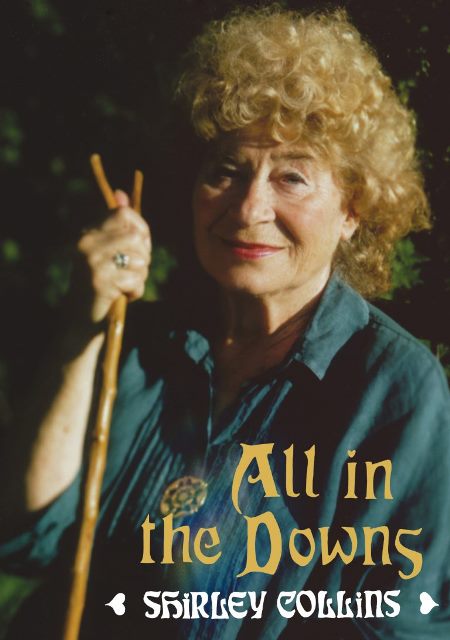

A return from the “long layoff” was hinted at in 1996 when she sang on The Starres are Marching Sadly Home album by Current 93, the outfit led by her long-time supporter David Tibet. He then talked her into taking a stage for the first time for three decades – she sang two songs in an unannounced solo spot at a Current 93 Union Chapel show on 10 February 2014. Since then, there have been Lodestar, the biographical film The Ballad of Shirley Collins and last year's publication of her absorbing autobiography All in the Downs. And next week, on 31 January, Shirley Collins & the Lodestar Band play The Roundhouse.

A return from the “long layoff” was hinted at in 1996 when she sang on The Starres are Marching Sadly Home album by Current 93, the outfit led by her long-time supporter David Tibet. He then talked her into taking a stage for the first time for three decades – she sang two songs in an unannounced solo spot at a Current 93 Union Chapel show on 10 February 2014. Since then, there have been Lodestar, the biographical film The Ballad of Shirley Collins and last year's publication of her absorbing autobiography All in the Downs. And next week, on 31 January, Shirley Collins & the Lodestar Band play The Roundhouse.

In the run-up to the show, Shirley took time to talk at her Sussex home. She was born on 5 July 1935 but nothing about her suggests she is in her eighties. As will be seen, she has engagingly robust views which are expressed without hubris. She is hugely charming. Funny as well. There is no flim-flam with Shirley Collins. Read on to discover some of her rather surprising musical favourites.

KIERON TYLER: You last played the Roundhouse in 1969, what can we expect this time?

SHIRLEY COLLINS: I’m still working with the Lodestar band who accompanied me on the album a couple of years ago after such an a long break from recording. There will be lots of new material as well – new material I haven’t recorded before or even sung before. It’s still traditional songs or ballads but they’re new to me and, so I imagine, the audience. The only thing I remember about the evening in 1969 is Dolly and I getting heckled when we started up. We were so totally different from anything else that was on. I was spirited enough to have a go back [at the heckling] and it all calmed down, and they seemed to quite like us after that. Whoever was shouting didn’t want us to continue playing English traditional music on a flute organ. My memory is us winning through and having an enjoyable evening.

Your major on-stage comeback was at the Barbican in February 2017 after Lodestar was released.

At the Barbican, at that time, I wasn’t sure whether people would come to see me after that long layoff. So we invited these other singers, friends and lovely musicians to play as well. I’d done talks at various places, but it was a long layoff and a couple of generations had grown up in that time and wouldn’t necessarily know who I was or what I did. I knew I had some support from older people but what turned out to be quite remarkable about the concerts we’ve done later is that they are full of young people. At Supersonic Festival in Birmingham – the least likely sounding festival for me to do where it’s [musical] cacophony! So very urban as well. There were girls there shouting “Shirley, Shirley.”

Your layoff ended following your first encounter with David Tibet. Did you think his interest was odd? What with his background in psychic TV and being in Current 93 ...

Your layoff ended following your first encounter with David Tibet. Did you think his interest was odd? What with his background in psychic TV and being in Current 93 ...

I thought it was extremely odd, especially since he said I was one of his two favourite singers and the other singer was Tiny Tim. It made me think "blimey, who is this?" Then he played me his music and I didn’t understand it, and I still don’t really. It’s not my sort of thing yet the person, David himself – we got on like a house on fire and it’s an enduring friendship. He asked me do The Union Chapel and I stepped on stage as a singer for the first time in so long. We did it. Ian Kearey accompanied me and there was dear old Tibet egging me on. Tibet had asked for about 20 years to do a gig for him and I’d said no for about the first five or 10 years. He kept pestering me. Then I backed down a bit and said “perhaps.” Finally, at The Union Chapel I said yes and did it. (pictured right: Shirley with David Tibet, 1992)

Were you terrified beforehand?

Yes. And during. David asked me to sing “All the Pretty Little Horses” which is not something I would really choose to sing but “Death and the Lady” I knew I could sing, especially with Ian Kearey’s slide guitar arrangement which was so wonderful to sing against. But I was scared all the way through and I couldn’t control my voice and breath. At least I had done it. A little confidence started seeping in.

Had you considered voice training to help recover your singing voice?

Had you considered voice training to help recover your singing voice?

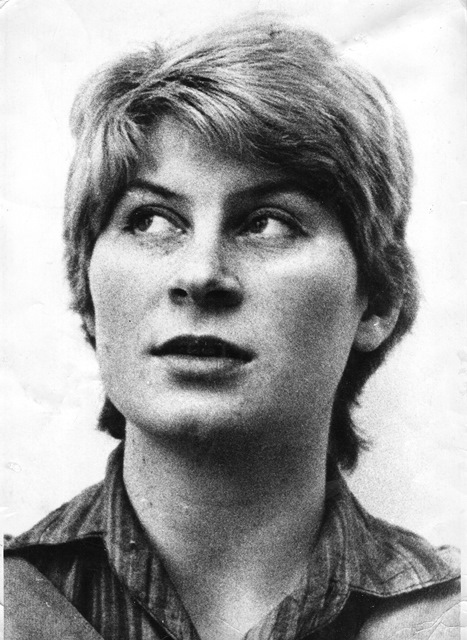

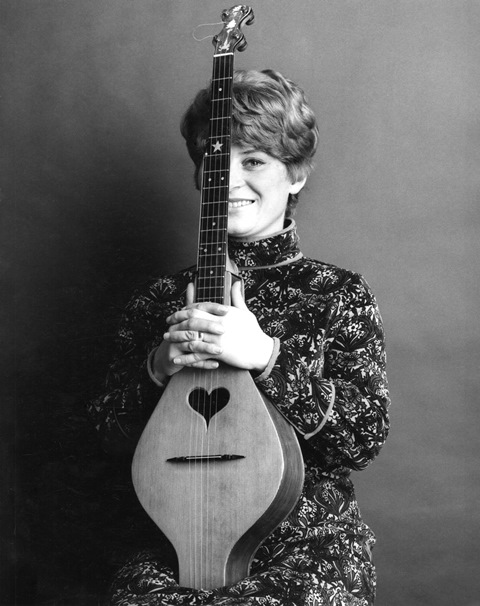

I’d gone though all that malarkey. Visited all sorts of quacks and proper doctors. Somebody at the National Theatre gave me some tuition but it was still too close to the time I was heartbroken. Later on, I tried a singing teacher. What I mostly got from that was being told that my accent wasn’t right for singing. When you listen to classically trained singers, the way the words are sung, I think it’s ghastly unless they’re singing in Italian. I don’t like the way trained singers sing in English. My voice has got better since Lodestar. Now I can sing out because I’m used to singing in front of larger audiences. In the folk club days I could sing louder and clearer. You had to sing out like that in the days before it was felt suitable for folk singers to have microphones. (pictured left: Shirley, 1963. Photo by David Sim)

When you were unable to sing, what came out when you tried?

Nothing. I would try a couple of notes and oh God... I was absolutely horrible. I was happy to talk in public, but not to sing. I couldn’t even join in a chorus in a folk club if I wanted to sing along. But I was still listening to music while I was not singing and songs were sinking in.

You were driven to sing from when you were very young and a letter you wrote generated a visit from Bob Copper. What was your reaction when he turned up at your family home?

I was thrilled to bits and a bit scared as well of course. It was thrilling as I’d heard of this man and he was so lovely, very avuncular, a warm person. But Dolly and I blew it. We tried to impress him. Instead of singing one of the family songs like my Aunt Grace’s “Just as the Tide Was Flowing” we had learned some songs off the radio. We sang “The Bonnie Earl o' Moray” in the best Scots accents we could summon. I was 15 then. Bob later gave me his worksheet [for that day: he was working for the BBC, finding traditional singers to record] and it said “Shirley Collins. Occupation: schoolgirl.”

Aren't you being hard on yourself? You didn't blow it - you were first on a record in 1955, and more followed shortly after that.

Aren't you being hard on yourself? You didn't blow it - you were first on a record in 1955, and more followed shortly after that.

It’s easier to be hard on yourself. You get in first in case other people are going to. That’s something I hadn’t thought of before. I think I come from a family who turn the joke against themselves. I don’t think I was being hard on myself, it was amusing what we had done and that we didn’t ruin the chance. Bob must have seen something there. He went in to speak to Granny and Granddad and they got on very well. They lived two doors away from us. I had this burning desire to sing and by 18 I was up in London. It was in me, the Englishness, the way the melodies were and I loved them. (pictured right: The 1955 compilation album Folk Song Today, the first album on which Shirley appeared)

When you got to London and were at Cecil Sharp House, the home of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, you've said the library was locked and it was hard to see the collections. Did the people there think you were a bit of a pest?

I’m sure they did. It was frightfully upper class people. The people who after all had the wherewithal – the leisure time – to study this. The librarian was really fierce. Why they wouldn’t let anyone who was obviously interested? It’s almost criminal.

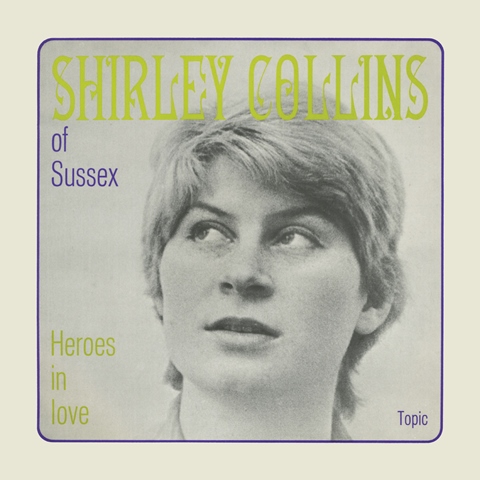

For the Topic EP from 1963 you are "Shirley Collins of Sussex". Then there is 1959's "English Songs" EP. Was linking your name with a place a conscious branding?

For the Topic EP from 1963 you are "Shirley Collins of Sussex". Then there is 1959's "English Songs" EP. Was linking your name with a place a conscious branding?

It was always essential to me that I was known as an English singer. Even today when people ask I always say I’m an “English Singer.” The English tradition is so rich, so unique. Glimpses of Irish and Scottish of course because of all the intermingling, swapping songs. There is an English quality to the songs I love. There was so much American stuff going on at the time, you really had to dig your heels in. But I was also so fascinated by the Appalachian stuff where there were still strong attachments [in the songs] to home. I didn’t want to sing the American stuff everyone sang. (pictured left: the 1963 EP credited to "Shirley Collins of Sussex")

For Alan Lomax's book The Folk Songs of North America, you're credited as "editorial assistant" and acknowledged in his introduction. What did you actually do for the book? Did you get paid?

Peggy Seeger did all the tunes, she notated all the tunes. I was basically a typist. I typed all the words, everything that Alan wrote. I don’t remember having any editorial duties – thoughts about the writing itself, though I was talking things over with Alan. He liked to talk about what he was doing. All these things were going in as I was typing. I didn’t get paid – I lived in [laughs uproariously]. In a way, I got paid in as much as before Alan went back to America he and Peter Kennedy recorded two whole LPs [her first two albums: Sweet England, issued in 1959, and False True Lovers, issued in 1960]. That was Alan’s way of saying “goodbye, sorry I’m not taking you with me.” It was sad time when he went.

Your involvement with the songs of America and of England mean your feet are on both sides of the Atlantic. The Folk Songs of North America was a touchstone for Roger McGuinn of The Byrds, and for Bob Dylan, too. You have had an influence in America.

Your involvement with the songs of America and of England mean your feet are on both sides of the Atlantic. The Folk Songs of North America was a touchstone for Roger McGuinn of The Byrds, and for Bob Dylan, too. You have had an influence in America.

It sounds vain, but I think I’ve got a better understanding for the Appalachian music and the English music than anyone else. Just because I’ve been at it for so long, so totally enamoured of it and fascinated by it. It’s a devotion. That sounds so serious but it’s been wonderful to be the person I am and know this stuff. (pictured right: Shirley, 1967. Photo by Brian Shuel)

In about 1965 or 1966, when The Byrds did their version of "The Bells of Rhymney", what did you think of that sort of thing getting into the charts?

I wasn’t listening to stuff like that. I grew up at a time there was no pop music on the radio and I was so immersed in traditional music. I listened occasionally to The Beatles when someone played it, but I didn’t listen to pop music. It’s not music for me, or sung for me.

Skiffle?

[Laughs even harder than before] That was so wicked of Lonnie Donegan to claim Leadbelly’s songs. Billy Bragg thinks skiffle was an important staging in working class music.

Should people know the source of what they're covering or perhaps mangling?

If they’re mangling it, I don’t suppose there’s much point in them knowing. But I think people ought to know the source, where it’s coming from. A strong point I always try to make is that not knowing is denying the people who kept the music going – people from England who are not really acknowledged by the people who have profited from it.

Did you ever have a yen to be popular as such?

Did you ever have a yen to be popular as such?

There was no way I could ever sing to be popular because of the material I was doing and the way I sang. I was coming through at a time when Shirley Abicair, the Australian zither player, was on television a lot. She was very pretty and sang songs that weren’t too difficult for people to understand. Then Julie Felix came in, who was equally lovely and played guitar and had long hair and played on all the television programmes. She would appear on David Frost singing Pete Seeger’s “let’s go to the zoo, zoo. zoo…” I couldn’t demean myself to do stuff like that. It’s not what I wanted to do. I had this great music to sing. I don’t think I ever saw myself in terms of a career. (pictured left: Shirley, 1967. Photo by David Montgomery)

In All in the Downs it's very funny when you recount being mistaken for Judy Collins.

Her voice was everywhere and a lot of people in the clubs were singing her songs and Joan Baez songs, and that’s what they thought folk music was.

You're very robust about jazz in All in the Downs.

That makes me feel ill when I hear it. I don’t like the way it sounds. I hate watching people play it. I can’t help it.

Isn't that sweeping?

Of course [more untrammelled laughter]. I really can’t help it and perhaps I ought to listen to it more. But you weren’t married to a man who played Miles Davis and Chet Baker at home all the time and went to jazz clubs and brought jazz musicians home who would leach on us. He was playing jazz and I just couldn’t get to it. It is sweeping. I’m allowed.

But your then-husband also brought Jimi Hendrix home.

But your then-husband also brought Jimi Hendrix home.

Jimi Hendrix is the most wonderful person you could have met. Dolly and I were on the same festival with him. Watching him play was the most thrilling thing, one of the best things I ever saw. Him and Muddy Waters were my most favourite musicians to watch. There was sweetness about Jimi, he was a lovely person and his music was sensational. There wasn’t another Jimi Hendrix was there? (pictured right: Shirley with her sister Dolly and a ram at Woburn Festival, 6 July 1968. Photo by Brian Shuel)

You were brushing close to the British underground music scene. You've talked about produced Joe Boyd trying to turn you into another Sandy Denny and, a little later, you and Dolly were on Harvest.

Harvest were quite happy to let us be what we were. When we made The Power of the True Love Knot [in 1967, pictured below left], Joe Boyd didn’t know quite what to do with me. Sandy was his great find. Obviously, Sandy was so special and wonderful – why wouldn’t somebody be looking for another Sandy Denny? Sandy was the beacon for everybody. Sandy could sing “A Sailor’s Life”, “The Banks of the Nile” wonderfully, beautifully. It moves you and thrills you at the same time. Who could resist Liege & Lief? Joe tried to make me sing in a way that was less straightforward, with more zing and expression. I think that’s why he brought the Incredible String Band into The Power of the True Love Knot, to make it more fun. The Incredible String Band were so lovely and fresh and captivating. I saw them live and you fell under their spell, so fey and beautiful and they said poignant and meaningful things in their lyrics. But I didn’t get out to concerts much then as I was at home with the kids.

What was your reaction when Anne Briggs started making records that were more singer-songwriter albums than traditional music?

What was your reaction when Anne Briggs started making records that were more singer-songwriter albums than traditional music?

I thought it was a really sad moment as she was a beautiful singer. I thought “get back to what you’re really good at.” Her “Willie o'Winsbury” is one of the loveliest things you’ll ever hear. She had a great voice. She was a wild child, yet she allowed that wildness to dissipate into a stew of semi-pop stuff.

It was surprising you worked on the video for sigur rós's "Ekki Muk".

My daughter had played me some sigur rós. The quality of the voice is just extraordinary. It’s fascinating, rather beautiful music.

That makes me wonder about you as a relatively dispassionate judge of what makes some music stand out.

Yes, why not? An example is that I love The Band. “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” is one of the greatest songs ever. But only when sung by Levon Helm. If it’s Joan Baez, forget it. When sung by them, it’s just extraordinary, really powerful. It’s not as if I don’t like any pop music or don't listen to any. I absolutely love “King of Wishful Thinking” by Go West, from the Pretty Woman film. Absolutely thrilling, knocks my sock off. Just gorgeous, so sexy. I like Mark Knopfler. He plays and composes beautifully. I know it’s not fashionable to [like him]. R.E.M., “Everybody Hurts” is one of my favourites. There’s some pop songs which almost mean as much as traditional songs, they just grab hold of you.

Someone who writes a song with an acoustic guitar and then sings it - are they a folk singer?

They’re not, are they? It’s one of the things which drives me mad that everyone seems to think anything goes with folk music. If you have lived it as long as I have, you know what real folk music is. Singer-songwriters are just not folk music. They are singer-songwriters. If you sing folk songs, you could call yourself a folk singer – but there’s a tad more to it than that.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

Add comment