theartsdesk at the Istanbul Music Festival: classics alla Turca | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Istanbul Music Festival: classics alla Turca

theartsdesk at the Istanbul Music Festival: classics alla Turca

A top Turkish orchestra and a legendary native pianist do their great city proud

Flashback to 1981, when the Bolshoy Ballet danced Swan Lake Act Two to a tinny Melodiya recording in Istanbul's Open-Air Theatre (seats were cheap for Interrailing students). Turkey was friends with the Soviet Union then. It hadn't been in the 1950s, when Turkish pianist and citoyenne du monde İdil Biret was advised not to play a Prokofiev sonata in her motherland.

Strong enough in recent years to have split off from the jazz and theatre the city has also been able to celebrate so well (I remember Oscar Peterson too from that student holiday), the 44th Music Festival was able to focus on Turkish artists during its opening days. Visitors promised for future concerts, including Murray Perahia, Maxim Vengerov, Isabel van Keulen and Angel Blue, would confirm its international status, but there was no need for any of the musicians I heard in five of the concerts to fear comparisons with their western counterparts.

You could question why no Turkish classical music, following a distinct, melancholy-tinged Beethoven/Rossini line from the Ottomans in the mid 19th century onwards, was on the programme, nor anything from the traditional sanat (a native word for "classical") repertoire. But these are very hard times under Erdoğan, when ties with the rest of Europe need to be asserted, and who could blame the loyal audiences for wanting to hear the very best?

The reassuring start in the state-of-the-art Lütfi Kurdar Concert Hall - the auditorium on Taksim Square where I heard Midori on my first visit to the festival has long been closed for renovation - proved that though the Borusan players may have gone quiet to our ears in the three years since they gave an archetypal and winning Prom programme, they have not been idle. Music Director Sascha Goetzel, a Viennese import, has brought them up to international level in the eight years he's been here, playing his own violin and bringing in his father, a longer-term Vienna Philharmonic player, to show the strings how to create a certain sound while treasuring what's distinctive, especially about the woodwind.

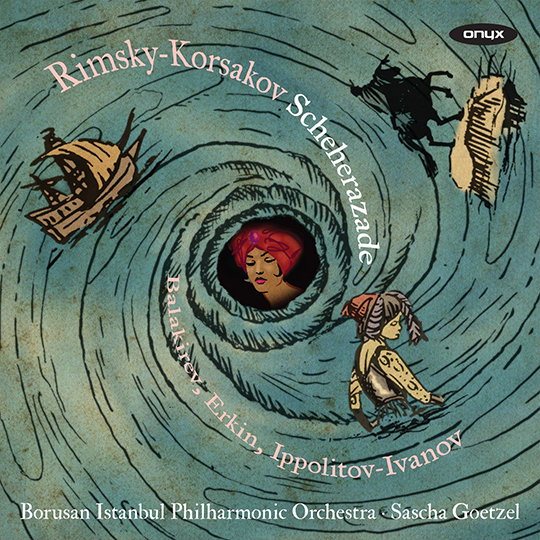

Sophistication has combined, as we know from three CDs already, with a passionate Turkish intensity to reclaim what Edward Said might have dismissed as "orientalist" music as its own (try the peerless CD of Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, much admired by Graham Rickson on theartsdesk, with oud and kanun joining harp in some of the sultana's "recitatives"). We had another taste of it in the Wednesday night encore, the riotous Bacchanal from Saint-Saëns' Samson et Dalila, where the belly-dancing tune, one of three sizzlers in the piece, transformed into something fierce and proud from the principal oboe and later the collective violins.

Sophistication has combined, as we know from three CDs already, with a passionate Turkish intensity to reclaim what Edward Said might have dismissed as "orientalist" music as its own (try the peerless CD of Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, much admired by Graham Rickson on theartsdesk, with oud and kanun joining harp in some of the sultana's "recitatives"). We had another taste of it in the Wednesday night encore, the riotous Bacchanal from Saint-Saëns' Samson et Dalila, where the belly-dancing tune, one of three sizzlers in the piece, transformed into something fierce and proud from the principal oboe and later the collective violins.

A firm showpiece identity established, the orchestra has gone on under Goetzel to give very fresh and vivid interpretations of Beethoven and Mozart. Their part in Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto was thoughtfully phrased and delicately balanced, as expected, but there wasn't much Goetzel could do to establish a rapport with Masleev, locked in his own world and, despite some nice largesse in the phrasing, too much the conventional prizewinner to find that dialogue with orchestra and conductor which makes any concerto performance worthwhile.

There was no doubt about the focus and fire in the first festival nod to Shakespeare 400, Shostakovich's incidental music to Kozintsev's 1964 Hamlet, one of the greatest Shakespeare films alongside the same partnership's later King Lear and producing a more substantial score than Shostakovich's circus-ring antics for a 1932 staging. Oddly, we tend to hear that more often and this was the first time I've encountered the whiplash terror of Shostakovich's Hamlet 2 in concert. The individual numbers join up to create a dark parallel to the greatest of the later symphonies, the Eighth, Tenth and Thirteenth. Borusan strings responded vividly to Goetzel's urging in raw, exposed unisons, brass reined in raw power and there's nothing anywhere else in the composer's output quite like the ticking, creeping music for the poisoning of the king in the play-within-a-play.

Uncompromising 20th century stature was also the keynote for the first of İdil Biret's three Istanbul Festival recitals in her 75th year (pictured above). Given her recent recording career with Naxos, it's easy to forget that she's not just one of the most prolific but also one of the greatest living pianists – still very much at heart the questing phenomenon whom Nadia Boulanger, Wilhelm Kempff and Alfred Cortot offered to teach without payment for their devotion.

The programme I heard launching the series unhyperbolically titled "The Piano Marathon of a Virtuoso" took place in the Albert Long Hall of the Bosphorus University's green and smart waterside campus. Biret amply justified the instantaneous standing ovation when she walked on to the platform. Some items in the blockbuster recital of Fauré, Bartók, Stravinsky, Ravel and Prokofiev – with Liszt's transcription of Schubert's "Auf dem Wasser zu singen" as a perfect pearl of an encore – worked better than others. The Three Pieces from Petrushka seemed a stretch too far in places, the bitonality of "Petrushka's Room" extending presumably unintentionally into what ought to be diatonic dances around it. But the power remains astonishing, as the second of Bartók's Two Elegies drove atmospherically home, and the delicacy, too; the rippling treble accompaniment of Ravel's "Ondine" in a mesmerising Gaspard de la Nuit emphasised the unique layering of which she is always capable.

Overwhelmed by what I’d been missing in concert over all these years, I managed to be granted an interview with the great lady on my final afternoon in Istanbul, courtesy of her charming husband Şefik Büyükyüksel, who, having retired from a high-flying job, now manages her career. They still have an apartment in the now chic Moda district on the Asian side of the Bosphorus, overlooking the Princes' Islands (always a keen swimmer, Biret remembers bathing in the waters of the bay when she was young – it's not clean enough now). The results of those two hours we spent together will appear in a Q&A for theartsdesk to coincide with the 75th birthday in November, but suffice it to say that I’ve never met a happier, more inquisitive or more grounded musician (she would say “optimistic”).

Around that meeting the day offered an embarrassment of riches. The previous evening’s Mendelssohn concert had been most remarkable for the charisma and grace of the great Turkish actress Tilbe Saran (pictured above with David Curtis and the Orchestra of the Swan), connecting every snippet and chunk of Mendelssohn’s complete incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Kudos to Ms Saran, too, for standing throughout the Overture and Scherzo and reacting so vividly to what she heard. In the diffuse acoustics of imposing Haghia Eirene in the grounds of the Topkapi Palace, the rest was less easy to judge, though Tamsin Waley-Cohen seemed to form an eloquent and charismatic partnership with David Curtis and the Orchestra of the Swan in Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, and her Bach encore was sheer heaven.

Venue and performance were perfectly blended in the four concerts I caught of the next day’s “Music Route”, a brilliantly manoeuvred excursion around churches off the main drag of the European Pera/Galata district, İstiklal Caddesi, achieved in two "shifts". The street, for all its chicification, somehow maintains much of the character, and many of the kind of characters, I remember from three previous visits, and the Christian communities as well as the consulates which were embassies centuries ago still keep going under unpromising present circumstances.

First up at 11am was young cellist Cansin Kara, looking heavenwards for inspiration which flowed easily in Bach’s Fourth Cello Suite, above all in a heavenly Sarabande, at the curtained altar of the Armenians’ Surp Yerrotutyun Church next to the famous Çiçek Pasajı (Flower Arcade). Five minutes’ walk brought us to the most elaborately decorated of the venues, the Greek Orthodox Church of Panayia Isodion (1804), appropriately spangled by the harp of Meriç Dönük alongside exquisite flautist Zeynep Keleşoğlu and viola-player Günsu Özkarar (pictured above).

Thunder rumbled and rain beat on the roof as the Viennese Auner Quartet turned in a perfectly modulated Schubert “Rosamunde” Quartet beneath the relatively recently decorated dome of Catholic Saint Anthony’s Lower Church, where a Chaldaean community hold services in Aramaic, the language of the Bible (I attended several in the south-eastern Turkish town of Mardin during the mid 1980s).

A reputedly elevating recital of Handel and Scarlatti from Daria van den Bercken in the Chapel of the Dutch Consulate had to be skipped in favour of lunch with Father Ian Sherwood, the remarkable Anglican vicar who in his 28 years in Istanbul has kept the Crimea Memorial Church from demolition and who hosts Pakistani and other Christian refugees in the district. His building, designed by the same architect responsible for London’s Law Courts, witnessed an electrifying mid-afernoon programme of Bach concertos from violinists Emre Engin – a major talent – and Camze Erengönül with the Istanbul Chamber Orchestra conducted by the obviously inspirational Hakan Şensoy (pictured below). This ensemble's ability to dance and to go even deeper towards the ends of movements might well be envied by countless counterparts.

There was further profound, more easily predicted enlightenment that evening in the art deco Süreyya Opera House, opened in 1927 in emulation of Paris's Théâtre des Champs-Élysées and a delicious ferry journey trip across the Bosphorus. Beneath a frieze of naked ladies on whom Turkey's religious conservatives must surely frown, pianist Maria João Pires and cellist Antonio Meneses (pictured below) gave an epic programme to mirror Biret's.

While Meneses was the easy grand master, effortless throughout the range if somehow going less directly to the heart than Cara in another Bach Cello Suite, Pires had revelations to offer in Beethoven’s Op 111 Piano Sonata. Not so much in the titanic first movement, which is a bit of a stretch for her in a way I suspect it still wouldn’t be for Biret, as in the conjunction of the famous proto-boogie-woogie variation of the Arietta, in which she engaged her entire body, with its heavenly successor, a voice from another planet.

It’s encouraging to know that in addition to housing the Istanbul State Opera, this beautifully restored venue also has a programme of Monday chamber recitals which has built a whole new audience for this most difficult of genres. Biret was playing Schubert and Liszt there in her second recital on the Sunday evening following my afternoon departure, but there was no cause for more than indulgent regrets; I’d had my visions.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Rajakesar, Selaocoe, The Hermes Experiment, Wigmore Hall review - a joyful, fascinating laboratory of noise

Celebrating the avant-garde through different cultures

Rajakesar, Selaocoe, The Hermes Experiment, Wigmore Hall review - a joyful, fascinating laboratory of noise

Celebrating the avant-garde through different cultures

Classical CDs: Vitamins, kings and magic spells

A neglected ballet score, romantic piano concertos and contemporary British music

Classical CDs: Vitamins, kings and magic spells

A neglected ballet score, romantic piano concertos and contemporary British music

Kavakos, Philharmonia, Blomstedt, RFH review - a supreme valediction forbidding mourning

Nonagenarian conductor provides the flow, his players the passion, in Mahler's Ninth

Kavakos, Philharmonia, Blomstedt, RFH review - a supreme valediction forbidding mourning

Nonagenarian conductor provides the flow, his players the passion, in Mahler's Ninth

Perianes, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Payare, Barbican review - elegance and drama but not enough bite

Often dynamic Venezuelan conductor misses the darkness of the 'Symphonie fantastique'

Perianes, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Payare, Barbican review - elegance and drama but not enough bite

Often dynamic Venezuelan conductor misses the darkness of the 'Symphonie fantastique'

La Serenissima, Wigmore Hall review - an Italian menu to savour

Tasty Baroque discoveries, tastefully delivered

La Serenissima, Wigmore Hall review - an Italian menu to savour

Tasty Baroque discoveries, tastefully delivered

Roman Rabinovich, Wigmore Hall review - full tone in four styles

Fascinating Haydn, Debussy and Schumann, odd Beethoven

Roman Rabinovich, Wigmore Hall review - full tone in four styles

Fascinating Haydn, Debussy and Schumann, odd Beethoven

Wyn, Dwyer, McAteer, RSNO & Choirs, Diakun, Usher Hall, Edinburgh review - ebullient but bitty

‘Carmina Burana’ is fun in parts, but Langer’s ‘Dong’ doesn’t flow

Wyn, Dwyer, McAteer, RSNO & Choirs, Diakun, Usher Hall, Edinburgh review - ebullient but bitty

‘Carmina Burana’ is fun in parts, but Langer’s ‘Dong’ doesn’t flow

Gerhardt, BBC Philharmonic, Chauhan, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - from grief to peace

Anna Clyne, Shostakovich and Richard Strauss tell us about loss, struggle and healing

Gerhardt, BBC Philharmonic, Chauhan, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - from grief to peace

Anna Clyne, Shostakovich and Richard Strauss tell us about loss, struggle and healing

First Person: Alec Frank-Gemmill on reasons for another recording of the Mozart horn concertos

On ignoring the composer's 'Basta, basta!' above the part for the original soloist

First Person: Alec Frank-Gemmill on reasons for another recording of the Mozart horn concertos

On ignoring the composer's 'Basta, basta!' above the part for the original soloist

Mailley-Smith, Piccadilly Sinfonietta, St Mary-le-Strand review - music in a resurgent venue

Neglected London church now the home of a vibrant concert series

Mailley-Smith, Piccadilly Sinfonietta, St Mary-le-Strand review - music in a resurgent venue

Neglected London church now the home of a vibrant concert series

Add comment