The Devil Inside, Peacock Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

The Devil Inside, Peacock Theatre

The Devil Inside, Peacock Theatre

Compelling new Faustian-pact opera is small in scale but big on ideas

"I wish I had money," exclaims the weak-willed hero of Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress and, hey presto, the devil appears to strike a deal. Auden and Kallman didn't have the last word on Faustian-pact librettos.

The Devil Inside has a gripping plot - especially if, like me, you hadn't read either story or synopsis in advance - and is flawlessly presented by a small team, shared between Scottish Opera in Glasgow, where the opera recently had its premiere, and Music Theatre Wales. Four singers, 14 instrumentalists and a conductor power ahead on all fronts.

First question, if this touring production is to have a longer life: does the music fit the subject-matter? Absolutely. Fidgety and spangled from the start, the superb small orchestra under Michael Rafferty punches above its nominal weight, as in the chamber operas of Britten. The colours are often bewitching, especially in the eerie music for harp and the deflating chromatic descents of lower instruments, and McRae has more than a few hockety ideas as catchy as Britten's.

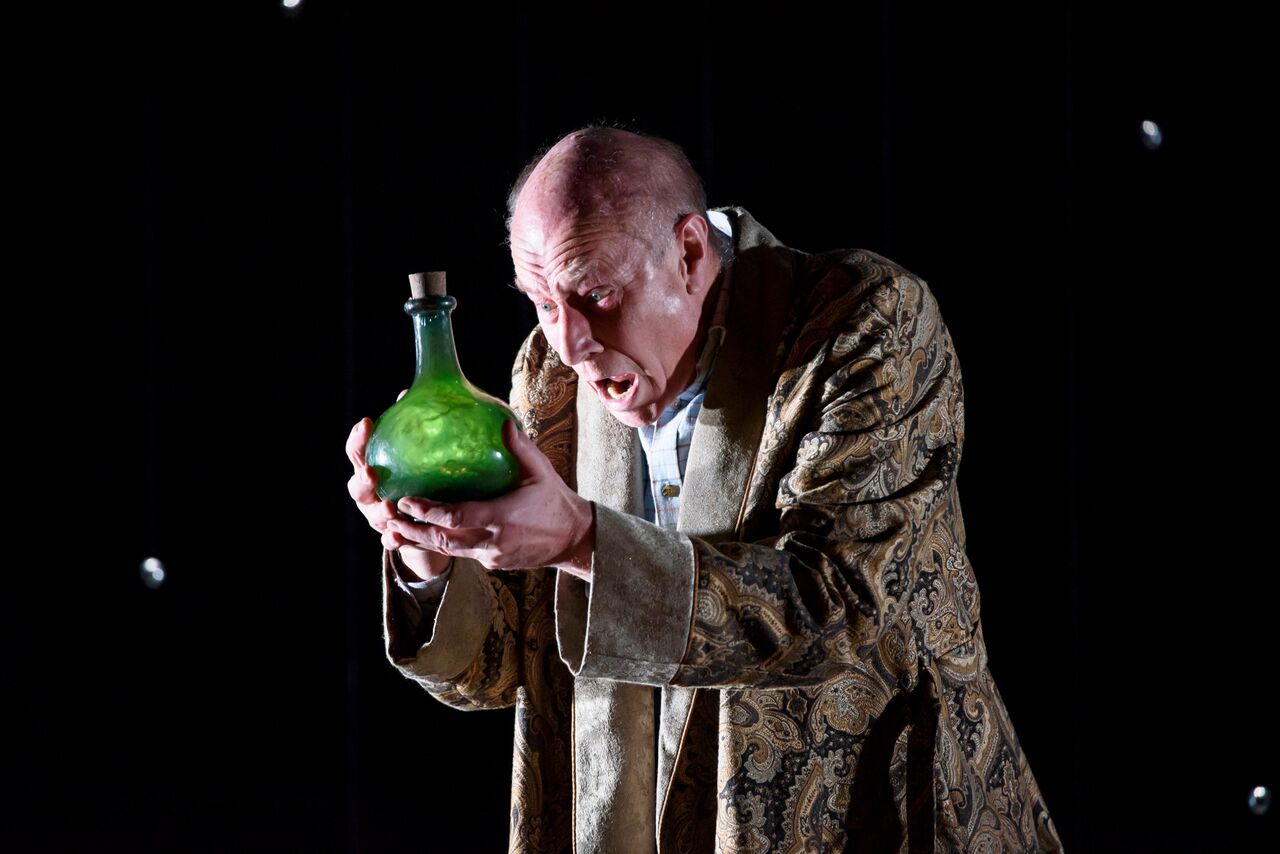

It has to be said that they're more often in the orchestra than in the voices; the singers have to grapple hard with writing that isn't exactly angular, but doesn't always fit the pithy text like a glove. The relatively few lyric moments are welcome but can feel contrived. Nicholas Sharratt as Richard, one of two lost hikers kicking off all the trouble in the mansion of a weird old man - Steven Page, commanding as ever (pictured above) - who wants to flog his green-glowing bottle complete with wish-granting imp inside for fifty dollars, has an arietta about what he'd do with the money rather too obviously flagged up. Baritone Ben McAteer's James gets big moments in the rich-financier scene, which came to a halt last night as the lights went off in the pit. Professional to a tee, Rafferty stopped cleanly, made an announcement while Sherratt quipped, and with illumination quickly restored. took the score back to the trumpet-capped interlude before the beginning of the scene.

It has to be said that they're more often in the orchestra than in the voices; the singers have to grapple hard with writing that isn't exactly angular, but doesn't always fit the pithy text like a glove. The relatively few lyric moments are welcome but can feel contrived. Nicholas Sharratt as Richard, one of two lost hikers kicking off all the trouble in the mansion of a weird old man - Steven Page, commanding as ever (pictured above) - who wants to flog his green-glowing bottle complete with wish-granting imp inside for fifty dollars, has an arietta about what he'd do with the money rather too obviously flagged up. Baritone Ben McAteer's James gets big moments in the rich-financier scene, which came to a halt last night as the lights went off in the pit. Professional to a tee, Rafferty stopped cleanly, made an announcement while Sherratt quipped, and with illumination quickly restored. took the score back to the trumpet-capped interlude before the beginning of the scene.

When James, who's sold the bottle on to his friend having accumulated wealth but not happiness, finds a wife, cue music of love and intimacy which temporarily seems to lose the dynamic thread. Were it not for the warmth and conviction of Rachel Kelly (pictured below with McAteer), already a superlative mezzo fresh out of the Royal Opera's Jette Parker Young Artists Programme, as love-interest Catherine, the action would falter before the interval. It probably wouldn't have needed one if the action had been shorn by a quarter of an hour, though there's enough ingenuity to keep it all afloat in Matthew Richardson's production and Samal Blak's designs, joining with Ace McCarron's spot-on lighting to make a virtue of economy in a way that puts the expensive complications of the sets for The Master Builder, which I saw the previous night, to shame. Stars light up the creepy mansion; curtains and double bed become stained with a dark, evil-butterfly design and black finally seeps downwards in a threat to kill off the light. Repetitions, like the two plane journeys, point up the symmetry of the dramatic shape.

It probably wouldn't have needed one if the action had been shorn by a quarter of an hour, though there's enough ingenuity to keep it all afloat in Matthew Richardson's production and Samal Blak's designs, joining with Ace McCarron's spot-on lighting to make a virtue of economy in a way that puts the expensive complications of the sets for The Master Builder, which I saw the previous night, to shame. Stars light up the creepy mansion; curtains and double bed become stained with a dark, evil-butterfly design and black finally seeps downwards in a threat to kill off the light. Repetitions, like the two plane journeys, point up the symmetry of the dramatic shape.

The screw truly begins to turn, musically speaking, in the second act. The ingenuity of Stevenson's devilish scheme is that the bottle can bring everything the owner desires, but it has to be sold on at a lower price if said owner is to avoid damnation. The threat of hell is possibly a bit of a snag in a secular 21st century context; as Tove Jansson's grandmother tells her granddaughter in The Summer Book, "You can see for yourself that life is hard enough without being punished for it afterwards". But it's music's task to make the supernatural seem real.

Admittedly with the pressure of Richard's drug-fuelled obsession and the desperate need to sell the bottle on for centimes comes an instrumental and vocal density that could also do with a bit of trimming. But the final twist, brilliantly devised by Walsh and MacRae, brings an ambiguous lightness. We could be witnessing the radiant beginnings of a new life, or the prequel to Rosemary's Baby. That's one of many ideas to mull over in this thought-provoking take on a myth with a difference, and even if it's not quite a masterwork, I sincerely hope The Devil Inside will be doing the rounds for years to come.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Simon Boccanegra, Opera North review - ‘dramatic staging’ proves its worth

Verdi’s political tragedy - and plea for peace - has impact in a grand Yorkshire setting

Simon Boccanegra, Opera North review - ‘dramatic staging’ proves its worth

Verdi’s political tragedy - and plea for peace - has impact in a grand Yorkshire setting

Peter Grimes, Welsh National Opera review - febrile energy and rage

In every sense a tour de force

Peter Grimes, Welsh National Opera review - febrile energy and rage

In every sense a tour de force

Owen Wingrave, RNCM, Manchester review - battle of a pacifist

Orpha Phelan brings on the big guns for Britten’s charge against war

Owen Wingrave, RNCM, Manchester review - battle of a pacifist

Orpha Phelan brings on the big guns for Britten’s charge against war

Tales of Apollo and Hercules, London Handel Festival review - compelling elements, but a failed experiment

Conceptually the two cantatas just don't work together

Tales of Apollo and Hercules, London Handel Festival review - compelling elements, but a failed experiment

Conceptually the two cantatas just don't work together

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

Add comment