The Exterminating Angel, Die Liebe der Danae, Salzburg Festival | reviews, news & interviews

The Exterminating Angel, Die Liebe der Danae, Salzburg Festival

The Exterminating Angel, Die Liebe der Danae, Salzburg Festival

Brilliant ensemble in Adès's new opera trumps a meaningless Strauss staging

"Because the world has outlived its own downfall, it nevertheless needs art." Paul Celan's words stand alongside Anselm Kiefer's Jacob's Dream, part of a stunning Surrealism-centric exhibition in the foyer of Salzburg's second and more amenable festival venue, the Haus für Mozart. What a meaningful motto it turned out to be for both of this year's major festival offerings, good and bad.

That downfall must have seemed final to the 80-year-old Richard Strauss as bombing curtailed the world premiere of his penultimate opera, Die Liebe der Danae, in 1944. Yet this far from shallow "cheerful mythology" returned to Salzburg for its coronation in 1952, then in 2002, and now in an expensive charade by design-obsessed Alvis Hermanis. The festival audience, surely more showy and predominantly less cultured than in Strauss's time but otherwise presumably not much altered, seemed to lap it up. Thank heaven or hell, then, for this year's premiere, a production of Thomas Adès's The Exterminating Angel (****) which actually had something to say about the hermetic world of the Salzburg Festival today.

Luis Buñuel's subversive 1962 film and Adès's opera, long in the making, hold up a mirror to this kind of well-heeled milieu and smash it. The bourgeoisie and aristocrats under examination are a group of elegant ladies and gentlemen unable to leave after a strange dinner party, even though the door to the outside world remains open. The subterranean stream of consciousness which Buñuel achieved solely through images and derailing dinner-party dialogue seems to cry out for music, and Adès - orchestrally, at least - has responded brilliantly to the phantasmagoria.

His response is typically eclectic, avoiding one dominant sound-world for this dream-play in favour of dramatic lurches and characteristic pastiches distorting music familiar - Strauss waltzes and a grinding climax based on Bach's "Sheep may safely graze" - as well as more arcane, homages to the Spanish context in dance-numbers and to outsider figures in the Hebrew poetry which director-librettist Tom Cairns has incorporated into a much-adapted treatment of the screenplay. There is depth to the sound, the favouring of low, grumbling instruments, but not, I think, on a first hearing - and I should willingly undergo a second and third - to the substance. As conducted by the composer, it sounds like the overheated, dense polar opposite to the chill refinement of George Benjamin's Written on Skin. Adès's work is closer to masterpiece status, if not quite there, and a good deal more entertaining.

That has to be in large measure due to a superlative cast working within Hildegard Bechtler's stupendous sets and costumes - again, a mirror to Salzburg if not necessarily to the varied audience which received the work so ecstatically in the more human of the festival venues. Adès and Cairns have reduced Buñuel's main dramatis personae of Big Brother House participants from 19 to a mere 15, which with bit parts for the servants and outsiders makes this an expensive number to maintain in the repertoire.

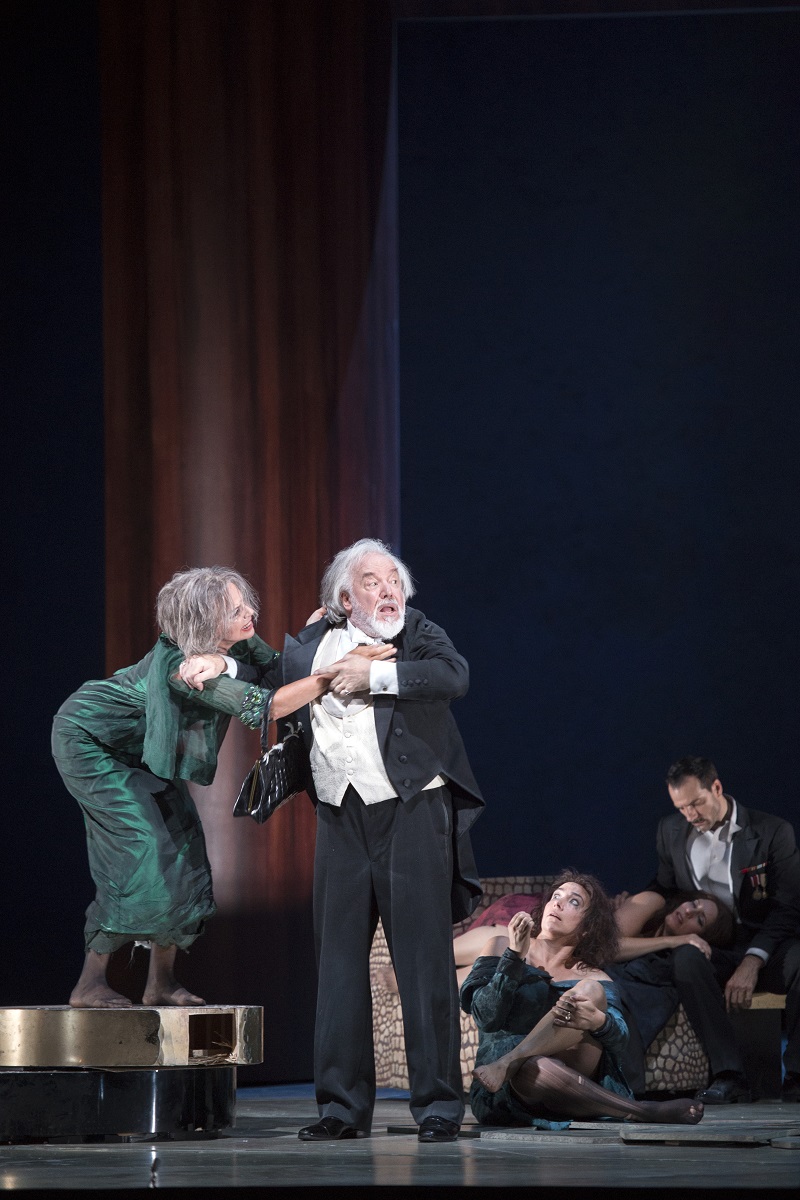

Act One is a confusion of ensembles - the greater precision of a Richard Jones as director would have pinpointed who's who more deftly, and probably been funnier - but eventually Adès gives ariettas and duets to personalities he wants to highlight. Making the most memorable impression are one of our greatest mezzos, Christine Rice, as the pianist Blanca Delgado, who sings a setting of Chaim Bialik's "Over the Sea"; countertenor Iestyn Davies as the neurotic, sibling-obsessed aristocrat Francisco de Ávila with his little number - quoting or pastiching what? - about inappropriate teaspoons for coffee; and Anne Sofie von Otter, back on top form after some dubious excursions, as a dying woman who gets a mad scene straitjacketed by guitar accompaniment (pictured above with John Tomlinson, Christine Rice and Frédéric Antoun).

Act One is a confusion of ensembles - the greater precision of a Richard Jones as director would have pinpointed who's who more deftly, and probably been funnier - but eventually Adès gives ariettas and duets to personalities he wants to highlight. Making the most memorable impression are one of our greatest mezzos, Christine Rice, as the pianist Blanca Delgado, who sings a setting of Chaim Bialik's "Over the Sea"; countertenor Iestyn Davies as the neurotic, sibling-obsessed aristocrat Francisco de Ávila with his little number - quoting or pastiching what? - about inappropriate teaspoons for coffee; and Anne Sofie von Otter, back on top form after some dubious excursions, as a dying woman who gets a mad scene straitjacketed by guitar accompaniment (pictured above with John Tomlinson, Christine Rice and Frédéric Antoun).

If there's a main character, it might be the diva and "virgin savage Walküre" Leticia Maynar. Since she's supposed to have just performed Lucia di Lammermoor, Ades gives Audrey Luna (pictured below standing with glass; also featured - Amanda Echalaz, Iestyn Davies and Sally Matthews) more of the insane stratospheric writing of Ariel in The Tempest - Luna sang the role at the Met - and lets her lead the final Chaconne to a tentative freedom. There is haunting music for the love-death infatuation of the betrothed couple Beatriz (Sophie Bevan) and Edmondo (Ed Lyon). But everyone else makes a mark. Impossible to credit them all, but let’s settle for Sally Matthews as the overloved sister, Amanda Echalaz as the flamboyant if word-cloudy hostess, John Tomlinson's overbearing Doctor and Thomas Allen making the most of his few lines as conductor Alberto Roc.

Such personalities help to paper over the chief drawback of Adès's operatic work: the often square, ungainly vocal writing. The awkwardness doesn't seem to be as pointed as Gerald Barry's much sparer and more differentiated stylisations, and the sopranos come off worst. When he's not pastiching, Adès doesn't quite hit the heights he aims for, least of all in the big final climax, though the orchestra interlude before it - the Bach distortion as the sheep the hostess had ordered for an unrealised diversion reappear for slaughter - duly stuns. Summoned by bells, ritual repetitions bind it all together, and the odd sound of the ondes martenot (Cynthia Millar, another welcome star "vocalist") suggest the invisible angel of the alluring title; but the musical screw doesn’t turn as inexorably as it might.

Still, it's all never less than gripping. What a relief the Salzburg management decided against the original idea of putting it on in the impossible Festspielhaus, that great barn with its wide stage. A saving grace of Hermanis's attempt to present Die Liebe der Danae (**) is his thrusting of all the action forward in front of a tiled wall. But there is no attempt at getting the singers to interact meaningfully, to bring out what's surely there in Strauss's late, often playful homage to the main theme of Wagner's Ring - true love versus power in the shape of gold.

How that might have resounded in a Bechtler-style reflection of the audience. Instead principals and chorus become flailing mannequins - in costumes opulently designed by Juozas Statkevičius - for a slightly dodgy recreation of Bakst/Diaghilev-style orientalism (pictured above:Jupiter disguised as Midas arrived on a white elephant), with chadored women in the last act mirroring heroine Danae's choice of a simple life in a way that verges on the insulting. It's as if Edward Said never wrote his study on Orientalism. There was never any point, anyway, in searching for depth. Not long in to the tedium of the first-act staging, bells began to ring: several years back, John Tomlinson made an on-the-record protest about a director who told the singers he didn't want them in a Salzburg staging of Birtwistle's Gawain, compelling him to block the action from memories of the Royal Opera production. That was Hermanis. And they asked him back?

Pity the principals, waving their arms ineffectually. Wince at the insistent movement by telly-spectacular choreographer Alla Sigalova for what looks like a group of schoolgirls whose teacher has asked if they can participate. And feel very sorry, if you know and love the score as I do, that there's no hint of the pathos in Jupiter's final meeting with his "last love" (Jupiters Letzte Liebe would have been a better title, one Strauss considered as he came to equate the god's farewell to earth with his own). If only the image pictured left could have been brought into focus and not overwhelmed by peripheral business..

Pity the principals, waving their arms ineffectually. Wince at the insistent movement by telly-spectacular choreographer Alla Sigalova for what looks like a group of schoolgirls whose teacher has asked if they can participate. And feel very sorry, if you know and love the score as I do, that there's no hint of the pathos in Jupiter's final meeting with his "last love" (Jupiters Letzte Liebe would have been a better title, one Strauss considered as he came to equate the god's farewell to earth with his own). If only the image pictured left could have been brought into focus and not overwhelmed by peripheral business..

Tomasz Konieczny is not quite right for Jupiter. He’s a robust bass-baritone in his prime, not a Hotter or a Norman Bailey close to the end of their careers. It's an insane sing, though, and very high at times; Koniecny only falls at the final hurdle. There's no competition from the man Danae really loves, Midas of the golden touch. I'd thought of Gerhard Siegel exclusively as character tenor. He turns out to have the stamina for Midas but not the vocal or physical glamour. Maybe the tenor singing the small role of Mercury, Norbert Ernst, might have made a better job; but then the demands are huge, and Siegel meets them.

Best is the glorious Krassimira Stoyanova (pictured below with dancers) as a lovely heroine. I knew her as a gracious and giving performer, but not that one in a thousand, the true Strauss lyric-dramatic soprano who can soar and swoop, working miracles on phrases that never stop coming. How she negotiated the highest of them all, late in the final scene, would be worth the high cost of admission alone.

Franz Welser-Möst, never an ideal Strauss conductor, can't match Stoyanova's generosity. He rushes too much of the music, above all the profundity of the great Act Three interlude, Four Last Songs territory: didn't he notice something wrong when the gruppetti or turns couldn't be articulated at that speed? The best that can be said is that the Vienna Philharmonic sound is right for this most sophisticated of scores and that Welser-Möst achieves an elegance in the lighter passages.

Most of these belong to the delectable quartet of Jupiter's discarded loves and the stories they bring with them, musically illustrated with diverting gorgeousness. The four ladies work well together, but the standouts are Maria Celeng as high-line Semele - an ideal Strauss light lyric soprano, as Regine Hangler's maid Xanthe is certainly not - and Jennifer Johnston, crystal-clear of diction and with all the stonking low notes Leda needs. She seemed to be having fun, but would have had more in David Fielding's super-inventive Garsington production, where the queens and their consorts were ballroom dancers.

Danae awaits a home-grown production at the Royal Opera. You can see why it doesn't get done often; to work at the highest level it needs the luxury musical resources - and presumably the rehearsal time - Salzburg wields. Yet if Covent Garden can host the difficulties of Adès, as it’s due to do next spring, it has an equal duty to serve the rarer, most sophisticated Strauss. Come on, Royal Opera, it's high time. But please, choose your director with care.

- Further performances of The Exterminating Angel and Die Liebe der Danae at the Salzburg Festival until 15 August

- Read more opera reviews on theartsdesk

- The Exterminating Angel arrives at the Royal Opera in April 2017

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Peter Grimes, Welsh National Opera review - febrile energy and rage

In every sense a tour de force

Peter Grimes, Welsh National Opera review - febrile energy and rage

In every sense a tour de force

Owen Wingrave, RNCM, Manchester review - battle of a pacifist

Orpha Phelan brings on the big guns for Britten’s charge against war

Owen Wingrave, RNCM, Manchester review - battle of a pacifist

Orpha Phelan brings on the big guns for Britten’s charge against war

Tales of Apollo and Hercules, London Handel Festival review - compelling elements, but a failed experiment

Conceptually the two cantatas just don't work together

Tales of Apollo and Hercules, London Handel Festival review - compelling elements, but a failed experiment

Conceptually the two cantatas just don't work together

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

Mary, Queen of Scots, English National Opera review - heroic effort for an overcooked history lesson

Heidi Stober delivers as beleaguered regent, but Thea Musgrave's opera is limiting

Mary, Queen of Scots, English National Opera review - heroic effort for an overcooked history lesson

Heidi Stober delivers as beleaguered regent, but Thea Musgrave's opera is limiting

Comments

Great read, David. I felt I

Great read, David. I felt I was there. So very informative.

Liam