La Fanciulla del West, Grange Park Opera | reviews, news & interviews

La Fanciulla del West, Grange Park Opera

La Fanciulla del West, Grange Park Opera

Puccini's gold rush melodrama is well sung but cramped by small theatre

Though composed after and based on a play by the same author, Puccini’s spaghetti western is in no way a sequel to Madama Butterfly, his whisky-sour eastern. Fanciulla is Butterfly’s opposite in almost every respect, and to tell the truth it isn’t much at home in a small theatre like the one at Grange Park.

Stephen Medcalf’s eight-year-old production, revived by Peter Relton, captures something of the work’s roughness and emotional crudity, but is often defeated by its episodic, stop-start discourse. Fanciulla is longer and more drawn-out than the best Puccini, and the seams aren’t always that well concealed. Its first quarter-hour or so of scene-setting, though some of the best music, could be sliced out without much damage to the plot. But this is also one of the best bits of the production, the various minor characters sharply drawn, finely sung, and smartly directed.

It’s quite like old times, and none the worse for that

Maybe it’s partly Puccini’s fault that the actual drama works so fitfully. The relationship between the bar-owner Minnie (Clare Rutter) and the disguised bandit Dick Johnson (Lorenzo Decaro), and everything to do with his unmasking, near-lynching and final rescue by Minnie herself (on a horse, according to Puccini’s super-elaborate stage directions, and with a pistol between her teeth), is so implausible that the production is sometimes reduced to presenting it more or less openly as a concert for soprano and tenor with the odd baritone intervention. At the end, with Minnie and Johnson riding off into the sunset waved goodbye by the miners who were just now hanging him from a tree, even these directors take refuge in parody, with the departing (horseless) lovers outlined against a huge, lurid rising sun while the weeping miners resume their homesick chorus from the first act.

This is, at any rate, a staging that for the most part respects Puccini’s clear mental picture of what his work is all about. The designer, Francis O’Connor, gives us a believable gold-rush bar, albeit with rather well-dressed miners, and a clever divided set for Minnie’s hut, which then slides away to leave us with the winter forest ready for the lynching. Snow falls, perhaps rather too obviously on cue. It’s really quite like old times, and none the worse for that, in a work of so obviously a genre character.

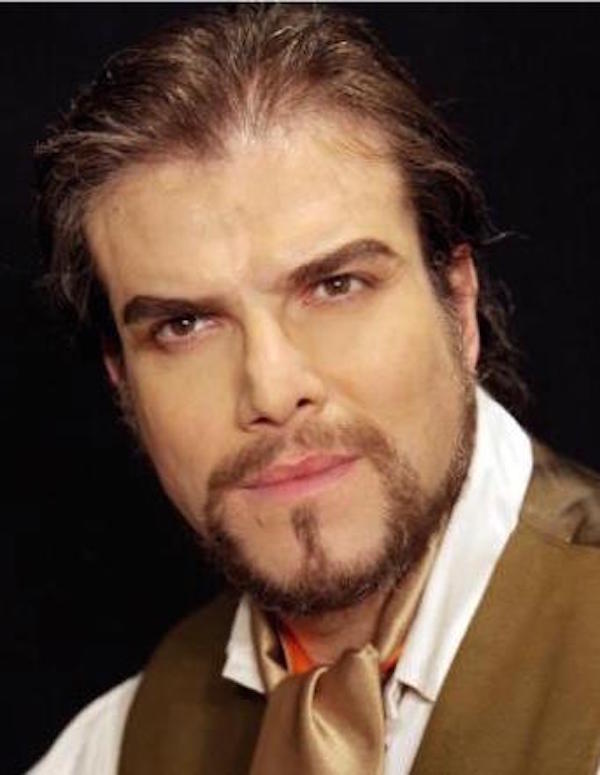

Musically, the star of the show is Decaro (pictured right), a tenor previously unknown to me, but a fine, uninhibited performer who blows into Minnie’s bar like the wind that later menaces her hut. One sometimes feels he needs La Scala to give due space to his ringing tones, but it’s a problem one can live with. Rutter is somewhat upstaged by her lover: a nice, stylish performer, but without the vivid stage presence that would go with her commanding position in the lives of these otherwise womanless outcasts. More interesting is Stephen Gadd’s portrait of the ambivalent figure of the sheriff, Jack Rance, driven to villainy by thwarted love, and certainly no instinctive Iago. His “Minnie, dalla mia casa” in the first act, about his loveless childhood, is touchingly, warmly sung.

Musically, the star of the show is Decaro (pictured right), a tenor previously unknown to me, but a fine, uninhibited performer who blows into Minnie’s bar like the wind that later menaces her hut. One sometimes feels he needs La Scala to give due space to his ringing tones, but it’s a problem one can live with. Rutter is somewhat upstaged by her lover: a nice, stylish performer, but without the vivid stage presence that would go with her commanding position in the lives of these otherwise womanless outcasts. More interesting is Stephen Gadd’s portrait of the ambivalent figure of the sheriff, Jack Rance, driven to villainy by thwarted love, and certainly no instinctive Iago. His “Minnie, dalla mia casa” in the first act, about his loveless childhood, is touchingly, warmly sung.

For the rest, this is a company show, with excellent individual contributions too numerous to list. Especially notable: Jihoon Kim’s deep-voiced Ashby (the Wells Fargo agent), Hanna-Liisa Kirchin’s touching vignette of the squaw Wowkle, Michel de Souza’s sonorous Sonora, and Thomas Humphreys’s brief glory as the camp minstrel Jake Wallace. Stephen Barlow conducts the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra tidily, if with big moments that sometimes swamp both stage and auditorium. But then Puccini wrote it that way, and for once his soft touch is largely absent.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment