Written on Skin, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Written on Skin, Barbican

Written on Skin, Barbican

An operatic story still etched as deeply as ever

You learn a lot about an opera in concert. Free from directorial and design intervention, the music can and must do it all. What is good is amplified, and what’s weak exposed. When that score is as psychologically rich and texturally varied as George Benjamin’s Written on Skin, the clarity of a concert performance can actually feel like a gain rather than a loss.

Which isn’t to belittle either Katie Mitchell’s original staging for the Aix Festival, or the work at the Barbican last night of director Benjamin Davis, who creates an allusive semi-staging within the significant restrictions of the Barbican Hall. But Benjamin’s score is so self-sufficient that it needs no help to etch its story deep into its audience.

It's Purves you can’t take your eyes off. The subtle rhetoric of his delivery is a marvel

The story has the same fable-like simplicity that gives Benjamin’s Into the Little Hill its elegant architecture. A love triangle sets a woman between two men – her husband, The Protector, and The Boy, an artist invited into their home. Control and authority clash with passion and anarchic freedom, and the results are brutal. A trio of angels (Victoria Simmonds, the excellent Robert Murray, and Tim Mead) watch the action play out with dispassionate interest.

Benjamin’s large orchestra dwarfs his cast of just five, but it’s a balance that reflects the dramatic responsibility of the instrumental music – poured into the spaces between Martin Crimp’s pared-back poetry. So when The Protector wheedles and needles The Boy into making him a book it’s the cellos that whine; when Benjamin reaches for an equal and opposite sound to the reedy purity of a countertenor he produces a bass viol; when he looks for a sonority to denature the romance of the harp he finds a guitar, and when Agnès finds herself driven to the brink of madness by her husband’s scheming it’s a glass harmonica, with its eerie echoes of Lucia, that flutters like the pulse at her temple.

Benjamin shifts the orchestra’s centre of gravity, setting it unusually low. The music is heavy with violas, and added to the prominence of low woodwind and brass this anchors even the flightiest shrieks of high strings and flutes, giving an apparently slight tale roots that go deep. This textural stability allows the composer to play more freely, shifting between the harmonic certainty of The Protector's early phrases and the ambiguity of The Boy’s, with their fluid relationship to harmony and tonality.

Benjamin shifts the orchestra’s centre of gravity, setting it unusually low. The music is heavy with violas, and added to the prominence of low woodwind and brass this anchors even the flightiest shrieks of high strings and flutes, giving an apparently slight tale roots that go deep. This textural stability allows the composer to play more freely, shifting between the harmonic certainty of The Protector's early phrases and the ambiguity of The Boy’s, with their fluid relationship to harmony and tonality.

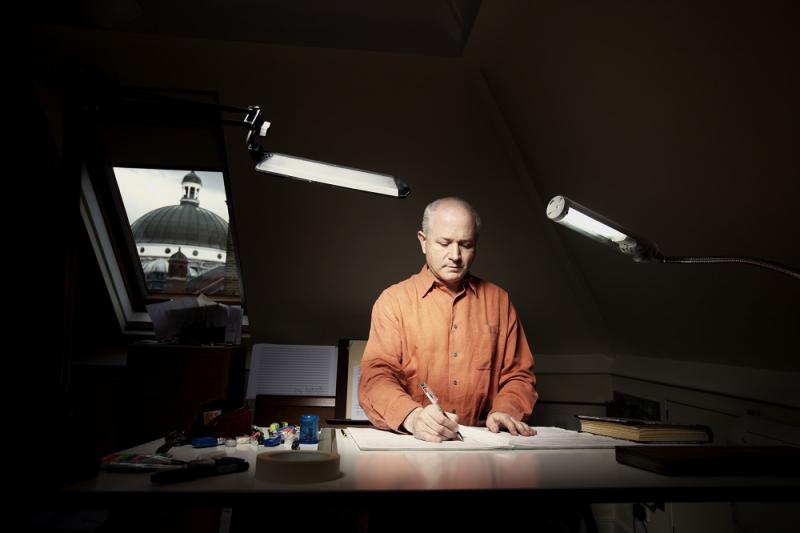

Benjamin himself (pictured below, at a Madrid performance ©Javier del Real, Teatro Real) conducted the Mahler Chamber Orchestra at the work’s 2012 premiere, and they return here alongside original cast members Barbara Hannigan and Christopher Purves (pictured above right). With an extended international tour of the opera already many months underway, last night’s performance was built on deep foundations. This is music that has been lived in, and it shows in the emotional and musical risks taken.

The central trio of Purves, Hannigan and Tim Mead as The Boy are all but unimprovable. Mead makes a chilly seducer, magnetic but horribly impassive. It’s a physical performance that’s the twin of his vocal delivery, which brings both Brittenish purity and Baroque power to bear on music that’s tainted even as it is exquisite. His duets with Hannigan are indecently sensual, sparking harmonics that ripple back through the orchestra. Hannigan herself is the perfect woman-child, by turns obstinate and ecstatic, bringing a muscularity to Benjamin’s high-lying writing that refuses to melt into bland beauty.

But it is Purves you can’t take your eyes off. The subtle rhetoric of his delivery is a marvel. The notes are just the start of expressive details and shading that render this tyrant disquietingly human. It is he who leads the orchestra into its sudden, cataclysmic flares of sound – moments where Benjamin treats his whole ensemble as a percussion section, striking and shaking them – and matches them in the heft of his anger, his violence.

But it is Purves you can’t take your eyes off. The subtle rhetoric of his delivery is a marvel. The notes are just the start of expressive details and shading that render this tyrant disquietingly human. It is he who leads the orchestra into its sudden, cataclysmic flares of sound – moments where Benjamin treats his whole ensemble as a percussion section, striking and shaking them – and matches them in the heft of his anger, his violence.

Benjamin has always been a miniaturist by instinct, working in detail but not necessarily in scope. In Written on Skin he retains all his concision, his immaculate restraint, but adds an emotional thrust that, even four years on from the premiere, still startles. He and Crimp return with a brand-new work for the Royal Opera House in 2018, and it’s hard not to be very excited about what that might bring.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

Mary, Queen of Scots, English National Opera review - heroic effort for an overcooked history lesson

Heidi Stober delivers as beleaguered regent, but Thea Musgrave's opera is limiting

Mary, Queen of Scots, English National Opera review - heroic effort for an overcooked history lesson

Heidi Stober delivers as beleaguered regent, but Thea Musgrave's opera is limiting

Festen, Royal Opera review - firing on every front

No slack in Mark-Anthony Turnage's operatic treatment of the visceral first Dogme film

Festen, Royal Opera review - firing on every front

No slack in Mark-Anthony Turnage's operatic treatment of the visceral first Dogme film

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera review - no concessions and no holds barred

Compelling revival, punches, placards and all

The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera review - no concessions and no holds barred

Compelling revival, punches, placards and all

Add comment