On An August Bank Holiday for a Lark | reviews, news & interviews

On An August Bank Holiday for a Lark

On An August Bank Holiday for a Lark

Playwright Deborah McAndrew introduces her new play inspired by World War One for Northern Broadsides

Shall I let you into a secret? Barrie Rutter isn’t always right. I’ve enjoyed a creative and rewarding professional relationship and personal friendship with Barrie for almost 20 years now, and I think I can say that without fear of him falling out with me. He isn’t always right – but he often is, and one of the things he’s right about is that a tragedy isn’t a tragedy until it’s a tragedy.

What does he mean? Well - notwithstanding the fact that outside the theatre in the mid-1590s Romeo and Juliet was advertised as a "Tragedy" and the Prologue tells us that the play will end with the deaths of the lovers, I can’t imagine that the play was presented with portentous misery from the off. It certainly isn’t written like that. Surely the highest achievement for a production of Romeo and Juliet even today is to draw the audience so fully into the moment that they can’t help daring to hope that, just this once, she’ll wake up in time?

Nobody foresaw what was round this blind corner in history

This is the challenge in writing a play about World War One. Even with a fictional narrative, a set of completely new characters, a different angle, everybody knows how it ends. A hundred years on, and despite Michael Gove having read a book to the contrary, the general consensus is that it was a catastrophic waste of young lives and, for those who survived, a trauma from which recovery was virtually impossible.

When Barrie (Rutter pictured below with the cast in rehearsal) asked me for a play to mark the centenary, he gave me the title – An August Bank Holiday Lark, taken from Philip Larkin’s poem "MCMXIV" - and the stipulation that the play be about folk dancing. Perhaps this sounds a little left-field, but for me it was a gift - a place to start that wasn’t full of darkness already.

I found my first "August Lark" quite quickly in the Rushcart traditions of the North West. This very practical custom of bearing rushes to the church as floor covering for the winter evolved into elaborate art in parts of Lancashire and West Yorkshire. The event involved teams of Morris dancers and was a feature of wakes weeks in the more rural towns and villages across the region throughout the 19th century.

I found my first "August Lark" quite quickly in the Rushcart traditions of the North West. This very practical custom of bearing rushes to the church as floor covering for the winter evolved into elaborate art in parts of Lancashire and West Yorkshire. The event involved teams of Morris dancers and was a feature of wakes weeks in the more rural towns and villages across the region throughout the 19th century.

The Rushcart has been successfully revived, most famously in Saddleworth - a weekend in August to which Morris men flock from all over the country, and which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. Like many folk traditions it’s a blend of pagan and Christian, joy and solemnity. It’s truly marvellous, a little bit mysterious and, to the outsider, completely bonkers. The Saddleworth Morris men have been a great help during my research and very generous with their knowledge and traditions.

The Rushcart gave me sunshine and flowers. It also gave me the social context for my play – the mill. Not in a city, but a small town, positioned above the urban sprawl and beneath the wide moorland skies, that would still have traditions rooted in a rural past. Helmshore in north-east Lancashire was the perfect model, and the excellent industrial museum there was my second source of research.

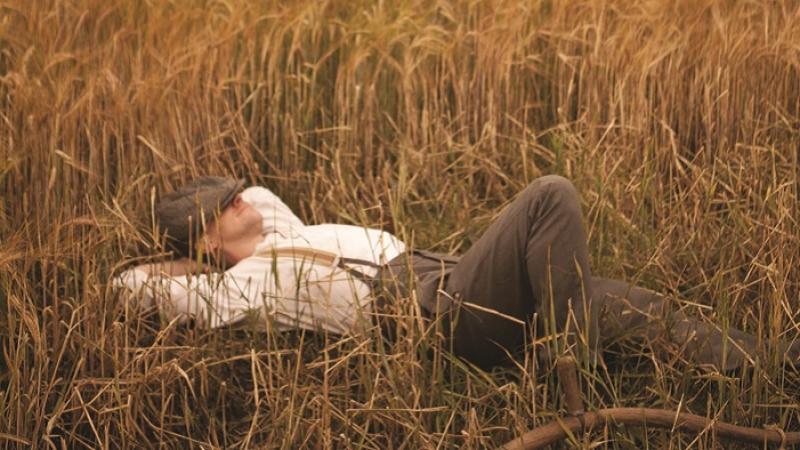

I was convinced that my play should remain at home, and never go into battle, as it were. I also felt that the Western Front had been covered very well in other plays – I’ve been in a production of Peter Whelan’s brilliant The Accrington Pals (Deborah McAndrew pictured left). I was also looking for a campaign that would chime ironically with my title. The August Offensive of 1915 was the last desperate attempt by the Allies to gain control of the Dardanelles. Most people associate the disastrous Gallipoli campaign with the ANZAC forces, but Ted Hughes’s father was a veteran and I knew that there were Yorkshire and Lancashire lads buried under the Turkish soil.

I was convinced that my play should remain at home, and never go into battle, as it were. I also felt that the Western Front had been covered very well in other plays – I’ve been in a production of Peter Whelan’s brilliant The Accrington Pals (Deborah McAndrew pictured left). I was also looking for a campaign that would chime ironically with my title. The August Offensive of 1915 was the last desperate attempt by the Allies to gain control of the Dardanelles. Most people associate the disastrous Gallipoli campaign with the ANZAC forces, but Ted Hughes’s father was a veteran and I knew that there were Yorkshire and Lancashire lads buried under the Turkish soil.

So I turned to the Regimental Museum at Fulwood Barracks in Preston and found what I was looking for – the 6th Battalion Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, and a real life story through which I could weave my fiction. There comes a point when a writer must leave the research and write, but this was a much more continuous process, with one informing the other - and all the time I kept returning to Larkin’s poem – a touchstone of innocence to keep my characters from becoming too knowing or self-conscious.

A play then in which people laughed and squabbled, courted and danced right up the moment when they didn’t any more. Nobody foresaw what was round this blind corner in history – and in the case of the Great War it wasn’t just loss of life, it was loss of trust. And nowhere is this expressed more eloquently than in the mournful last line of Larkin’s great poem - "never such innocence again".

more Theatre

Two Strangers (Carry A Cake Across New York), Criterion Theatre review - rueful and funny musical gets West End upgrade

A Brit and a New Yorker struggle to find common ground in lively new British musical

Two Strangers (Carry A Cake Across New York), Criterion Theatre review - rueful and funny musical gets West End upgrade

A Brit and a New Yorker struggle to find common ground in lively new British musical

Testmatch, Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Testmatch, Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Add comment