Ancient Greece: The Greatest Show on Earth, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Ancient Greece: The Greatest Show on Earth, BBC Four

Ancient Greece: The Greatest Show on Earth, BBC Four

The history of theatre and democracy go hand in hand

Brush up your geography and dust down your history – Dr Michael Scott is investigating the sources of Greek drama and their influence on all theatre to the present day. But he isn’t going to make it easy. The opening instalment of Ancient Greece: The Greatest Show on Earth, a three-parter, was a giddying ride out of Athens to the farthest-flung regions of Google.

His opening gambit, and indeed his conclusion in this somewhat circular tour, is that theatre and democracy emerged together, each supported by the other. Tragedy drew on earlier, real events to demonstrate, instructively, the consequences of bad judgement by flawed personalities. Comedy ridiculed the decision-makers of the day – by way of illustration, Cleon, depicted by Aristophanes as a cheating servant, who is finally brought down and resorts to selling sausages outside the city wall. This play is The Knights – although you could be forgiven for thinking it was in The Nights, because The Greatest Show on Earth is lamentably short of captions, wilfully allowing ambiguities and mishearings when a few letters on screen would make Scott’s undoubted erudition so much easier to absorb.

Why is television so terrified of visual aids, despite its name? Any amount of plinky-plunk background music that adds nothing to anything is almost de rigueur. But just suppose we are not all completely on top of the drama festival called the Lenaia already, or the Battle of Hysiae – or, indeed, the Pelopennesian war all told – would it be dumbing down beyond the depths of The Only Way is Essex to flash up some of those terms?

Why is television so terrified of visual aids, despite its name? Any amount of plinky-plunk background music that adds nothing to anything is almost de rigueur. But just suppose we are not all completely on top of the drama festival called the Lenaia already, or the Battle of Hysiae – or, indeed, the Pelopennesian war all told – would it be dumbing down beyond the depths of The Only Way is Essex to flash up some of those terms?

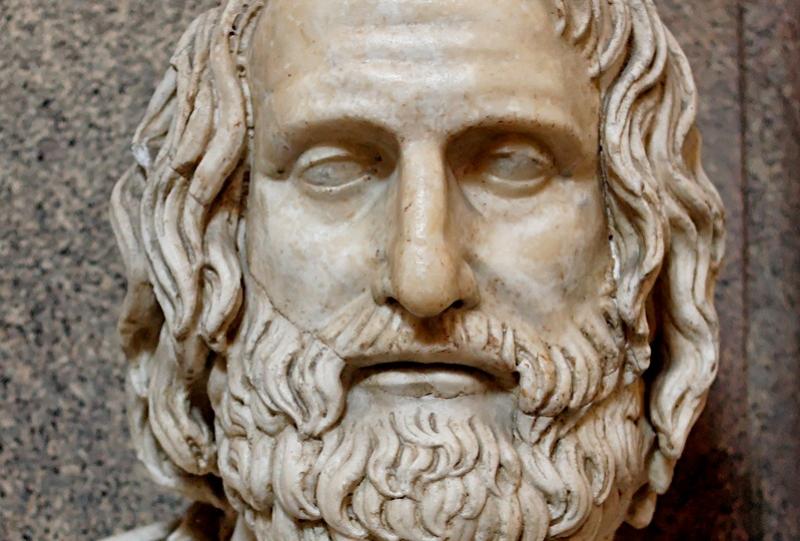

Nice for Scott to stroll through a fish market to illustrate the slithery nature of some politicians and wily Cleon’s taste for fresh-caught tuna (which was considered undemocratic, for reasons unexplained). But it is scant consolation for those of us trying to get our heads around the Ancient Greek for the targets for satire (not to be confused with the satyr plays). Komedumanoi apart, there is much to mull over here, not least the harrowing clips from Michael Cacoyannis’s 1971 film of The Trojan Women, Brian Blessed looming over Vanessa Redgrave, Katharine Hepburn looking on stonily (pictured above right), in Euripides’ still shocking depiction of the siege of Troy. Audiences in fifth-century Athens would have recognised parallels with the destruction of defiant Melos in 416 (look sharp, there's a map), the men all executed, the women and children taken captive.

Discussions with other academics take place by carefully positioned posters for modern-day productions, for example of the National Theatre’s Oedipus with Ralph Fiennes. This, presumably, to suggest that the 32 plays that survive from the 1,000 are still packing in the crowds, although there was no discussion with a director or actor from a current production, which would have made a refreshing change from Oxbridge colleagues chatting under a tree and proved that the dramas are pertinent, not museum pieces.

Discussions with other academics take place by carefully positioned posters for modern-day productions, for example of the National Theatre’s Oedipus with Ralph Fiennes. This, presumably, to suggest that the 32 plays that survive from the 1,000 are still packing in the crowds, although there was no discussion with a director or actor from a current production, which would have made a refreshing change from Oxbridge colleagues chatting under a tree and proved that the dramas are pertinent, not museum pieces.

That true democracy needs theatre and vice versa is an idea that may be explored in future episodes. It certainly stands up well at other flashpoints in history. This is a series to stick with, but have your laptop handy: if you can understand every point unaided, you’re probably in it.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Paris Has Fallen, Prime Video review - Afghan war veteran wreaks a terrible vengeance

Cynical politicians and amoral arms dealers feel the heat

Paris Has Fallen, Prime Video review - Afghan war veteran wreaks a terrible vengeance

Cynical politicians and amoral arms dealers feel the heat

Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light, BBC One review - handsome finale for Hilary Mantel adaptation

Mark Rylance is on top form as his Thomas Cromwell re-emerges after nine years

Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light, BBC One review - handsome finale for Hilary Mantel adaptation

Mark Rylance is on top form as his Thomas Cromwell re-emerges after nine years

The Day of the Jackal, Sky Atlantic review - Frederick Forsyth's assassin gets a modern-day makeover

Eddie Redmayne shoots to kill in lavish 10-part drama

The Day of the Jackal, Sky Atlantic review - Frederick Forsyth's assassin gets a modern-day makeover

Eddie Redmayne shoots to kill in lavish 10-part drama

Road Diary: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Disney+ review - the Boss grows older defiantly

Thom Zimny's film reels in 50 years of New Jersey's most famous export

Road Diary: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Disney+ review - the Boss grows older defiantly

Thom Zimny's film reels in 50 years of New Jersey's most famous export

Industry, BBC One review - bold, addictive saga about corporate culture now

Third season of the tale of investment bankers reaches a satisfying climax

Industry, BBC One review - bold, addictive saga about corporate culture now

Third season of the tale of investment bankers reaches a satisfying climax

Rivals, Disney+ review - adultery, skulduggery and political incorrectness

Back to the Eighties with Jilly Cooper's tales of the rich and infamous

Rivals, Disney+ review - adultery, skulduggery and political incorrectness

Back to the Eighties with Jilly Cooper's tales of the rich and infamous

Disclaimer, Apple TV+ review - a misfiring revenge saga from Alfonso Cuarón

Odd casting and weak scripting aren't a temptation to keep watching

Disclaimer, Apple TV+ review - a misfiring revenge saga from Alfonso Cuarón

Odd casting and weak scripting aren't a temptation to keep watching

Ludwig, BBC One review - entertaining spin on the brainy detective formula

David Mitchell is a perfect fit for this super-sleuth

Ludwig, BBC One review - entertaining spin on the brainy detective formula

David Mitchell is a perfect fit for this super-sleuth

The Hardacres, Channel 5 review - a fishy tale of upward mobility

Will everyday saga of Yorkshire folk strike a popular note?

The Hardacres, Channel 5 review - a fishy tale of upward mobility

Will everyday saga of Yorkshire folk strike a popular note?

Joan, ITV1 review - the roller-coaster career of a 1980s jewel thief

Brilliant performance by Sophie Turner as 'The Godmother'

Joan, ITV1 review - the roller-coaster career of a 1980s jewel thief

Brilliant performance by Sophie Turner as 'The Godmother'

The Penguin, Sky Atlantic review - power, corruption, lies and prosthetics

Colin Farrell makes a beast of himself in Batman spin-off

The Penguin, Sky Atlantic review - power, corruption, lies and prosthetics

Colin Farrell makes a beast of himself in Batman spin-off

Comments

I thought this was a great

I really enjoyed the