The Art of Gothic: Britain's Midnight Hour, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

The Art of Gothic: Britain's Midnight Hour, BBC Four

The Art of Gothic: Britain's Midnight Hour, BBC Four

Andrew Graham-Dixon's Gothic is a collective bad dream waiting to be psychoanalysed

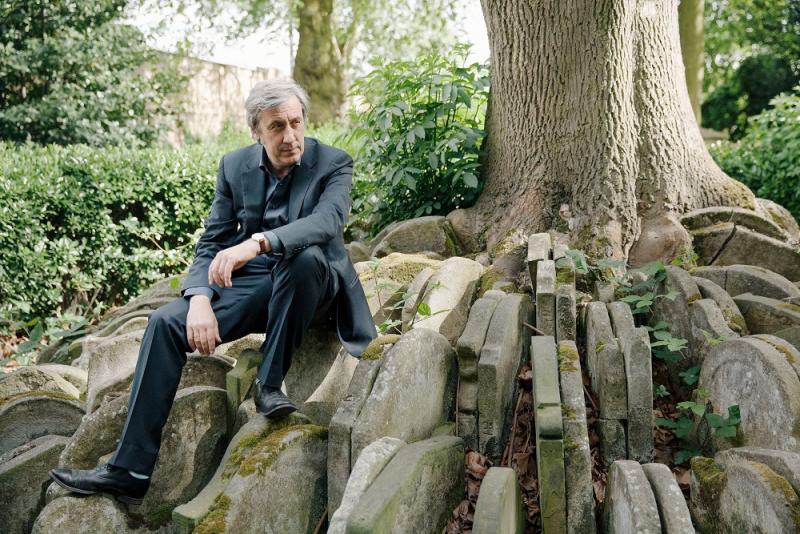

Andrew Graham-Dixon’s villainous alter ego got a second airing tonight in his exploration of 19th-century Britain’s love of all things Gothic. Last week we saw him hanging about in decaying graveyards, or appearing, wraithlike in a dank corner of a Gothic ruin, while ravens circled portentously overhead (main picture).

The great thing about Graham-Dixon’s exuberantly hammed-up delivery is that it is entirely in keeping with the subject. Throughout the series so far, he has switched between razor-sharp insight and Hammer Horror-style kitsch that emphasises not just his own enjoyment of Gothic but the endlessly malleable and enduring entertainment it represents. The Gothic sensibility is one of conflicting impulses and it moves constantly between moralising and titillation, conjuring nightmarish visions of the future and idealistic reimaginings of the past.

Characterising the 19th century as a time of suppressed emotions and barely articulated fears is hardly new, but the scope of tonight’s episode extended far beyond sensational Gothic novels to find the Gothic lurking in the most unlikely places. Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting, Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768 (pictured right), shows a family gathered around to watch as a travelling scientist slowly suffocates a bird in a jar, and it tends to be broadly interpreted as a celebration of science, a rebuttal to those who worried that the age of enlightenment might also usher in an age of unprecedented uncertainty.

Characterising the 19th century as a time of suppressed emotions and barely articulated fears is hardly new, but the scope of tonight’s episode extended far beyond sensational Gothic novels to find the Gothic lurking in the most unlikely places. Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting, Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768 (pictured right), shows a family gathered around to watch as a travelling scientist slowly suffocates a bird in a jar, and it tends to be broadly interpreted as a celebration of science, a rebuttal to those who worried that the age of enlightenment might also usher in an age of unprecedented uncertainty.

To Graham-Dixon, the extreme lighting that makes this scene such a compelling piece of drama is not the benevolent light of scientific progress, but the eery flash of a lightning strike, or perhaps something else entirely. The moon, glimpsed through the window, is a shorthand for the kind of haunted house so essential to Gothic novels while the wild-haired scientist, hardly the image of a man of reason, is recast as a magus or sorcerer from an ancient age of magic and superstition.

The painting is suddenly ambivalent, no longer cheerleading for scientific advancement but giving vent to the anxieties that accompanied it. Was God, like the dying bird, being killed by science? And if so, what would fill the vacuum?

The painting is suddenly ambivalent, no longer cheerleading for scientific advancement but giving vent to the anxieties that accompanied it. Was God, like the dying bird, being killed by science? And if so, what would fill the vacuum?

Such concerns about the Pandora’s box that science might open were nowhere more strenuously articulated than in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; even today Frankenstein is synonymous with irresponsible scientists, concerned more with the realisation of their ambitions than the moral obligations that come with scientific discovery.

Despite the dark turn taken by Gothic in the 19th century, it retained a brighter side that found expression though architecture. While the many Gothic ruins dotted across the landscape were a constant reminder of an ancient, lost Britain, their gargoyles and decaying masonry powerfully evocative of a primitive, superstitious past, for many, Gothic was a comforting reminder of a better time.

For AWN Pugin, so superior was the architecture of the Gothic that it presented the means by which salvation could be achieved. Hopelessly idealistic, Pugin believed that by recreating medieval cities and towns, where communities were built around churches, and life was quieter, more predictable and more ordered, modern civilisation could be saved from the self-destruction assured by the momentous changes of the Industrial Revolution.

Of his most famous project, the Houses of Parliament, “Pugin dreamed that this benevolent, conservative, feudal image of the past would stamp a moral vision on those who ran the country.” Instead, Graham-Dixon astutely observed, in its evocation of a glorious past, the architecture, “breeds a kind of soporific indifference to the problems of the present.” The natural reaction, in this building devoted to the affairs of the nation, is simply to fall asleep.

As Graham-Dixon wove a fascinating and cogent narrative about the collective psyche of Victorian Britain, as revealed by the use of Gothic in public buildings, from lunatic asylums to the Albert Memorial, I barely noticed that he was back in a graveyard, often a cue, it turns out, for some sort of Gothic role play (pictured above left). I’m afraid to say I almost jumped off the chair when he turned round, growling horribly, sporting a set of plastic fangs. I think it’s his way of saying that next week, he’ll be talking about Dracula.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Your Friends & Neighbors, Apple TV+ review - in every dream home a heartache

Jon Hamm finds his best role since 'Mad Men'

Your Friends & Neighbors, Apple TV+ review - in every dream home a heartache

Jon Hamm finds his best role since 'Mad Men'

MobLand, Paramount+ review - more guns, goons and gangsters from Guy Ritchie

High-powered cast impersonates the larcenous Harrigan dynasty

MobLand, Paramount+ review - more guns, goons and gangsters from Guy Ritchie

High-powered cast impersonates the larcenous Harrigan dynasty

This City is Ours, BBC One review - civil war rocks family cocaine racket

Terrific cast powers Stephen Butchard's Liverpool drug-ring saga

This City is Ours, BBC One review - civil war rocks family cocaine racket

Terrific cast powers Stephen Butchard's Liverpool drug-ring saga

The Potato Lab, Netflix review - a K-drama with heart and wit

Love among Korean potato-researchers is surprisingly funny and ideal for Janeites

The Potato Lab, Netflix review - a K-drama with heart and wit

Love among Korean potato-researchers is surprisingly funny and ideal for Janeites

Adolescence, Netflix review - Stephen Graham battles the phantom menace of the internet

How antisocial networks lead to real-life tragedy

Adolescence, Netflix review - Stephen Graham battles the phantom menace of the internet

How antisocial networks lead to real-life tragedy

Drive to Survive, Season 7, Netflix review - speed, scandal and skulduggery in the pitlane

The F1 documentary series is back on the pace

Drive to Survive, Season 7, Netflix review - speed, scandal and skulduggery in the pitlane

The F1 documentary series is back on the pace

A Cruel Love: The Ruth Ellis Story, ITV1 review - powerful dramatisation of the 1955 case that shocked the public

Lucy Boynton excels as the last woman to be executed in Britain

A Cruel Love: The Ruth Ellis Story, ITV1 review - powerful dramatisation of the 1955 case that shocked the public

Lucy Boynton excels as the last woman to be executed in Britain

Towards Zero, BBC One review - more entertaining parlour game than crime thriller

The latest Agatha Christie adaptation is well cast and lavishly done but a tad too sedate

Towards Zero, BBC One review - more entertaining parlour game than crime thriller

The latest Agatha Christie adaptation is well cast and lavishly done but a tad too sedate

Bergerac, U&Drama review - the Jersey 'tec is born again after 34 years

Damien Molony boldly follows in the hallowed footsteps of John Nettles

Bergerac, U&Drama review - the Jersey 'tec is born again after 34 years

Damien Molony boldly follows in the hallowed footsteps of John Nettles

A Thousand Blows, Disney+ review - Peaky Blinders comes to Ripper Street?

The prolific Steven Knight takes us back to a squalid Victorian London

A Thousand Blows, Disney+ review - Peaky Blinders comes to Ripper Street?

The prolific Steven Knight takes us back to a squalid Victorian London

Zero Day, Netflix review - can ex-President Robert De Niro save the Land of the Free?

Panic and paranoia run amok as cyber-hackers wreak havoc

Zero Day, Netflix review - can ex-President Robert De Niro save the Land of the Free?

Panic and paranoia run amok as cyber-hackers wreak havoc

The White Lotus, Series 3, Sky Atlantic review - hit formula with few surprises but a new bewitching soundtrack

Thailand hosts the latest bout of Mike White's satirical takedown of the rich and privileged

The White Lotus, Series 3, Sky Atlantic review - hit formula with few surprises but a new bewitching soundtrack

Thailand hosts the latest bout of Mike White's satirical takedown of the rich and privileged

Add comment