Basquiat: Rage to Riches review, BBC Two – death rides an equine skeleton | reviews, news & interviews

Basquiat: Rage to Riches review, BBC Two – death rides an equine skeleton

Basquiat: Rage to Riches review, BBC Two – death rides an equine skeleton

How the poor boy from Brooklyn became an art world supernova

An irresistible tragedy: young man of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, from Brooklyn, multilingual, brilliantly precocious, who left his middle class home to turn to street life in Manhattan, metamorphosing into a mesmerising graffiti artist. SAMO© was his response to "how are you?" Same old shit...

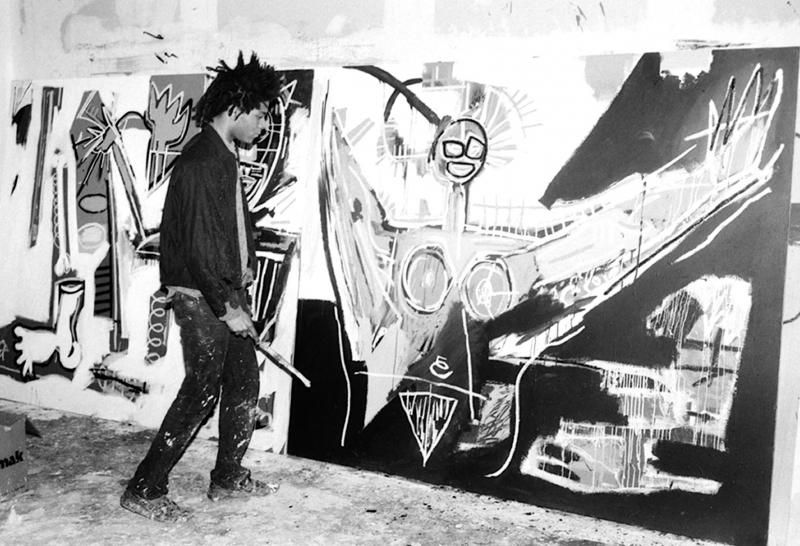

Living in the blitzed Lower East Side in the late 1970s and early 1980s when New York was nearly bankrupt and deserted by the conventional middle class was a moment of creative explosion; living was cheap and artists poured into the city. The East Village and north of Houston (Noho) and south of Houston St (Soho) were colonised by a growing community whose energies fed off each other, working every which way to make ends meet and to make their work. Jean-Michel Basquiat (pictured below) was so poor he raided burnt-out buildings for old doors to paint on.

Suzanne Mallock of Palestinian and English ancestry had come to New York when a teenager, from Canada. She thought her own mixed heritage helped her to understand Basquiat’s feelings of being an outsider and worked as a waitress, supporting Basquiat – they were barely 20 – while they lived together for a couple of years. He was incredibly prolific, creating something like 250 paintings and 500 drawings during that time. By his early 20s, through a combination of his surprising confidence and sheer audacity and nerve in putting himself forward and his hugely visible and original talent, he was showing in galleries and selling so much there were stashes of cash in his tiny apartment – and drugs. He was dead from a seemingly accidental overdose aged 27.

Suzanne Mallock of Palestinian and English ancestry had come to New York when a teenager, from Canada. She thought her own mixed heritage helped her to understand Basquiat’s feelings of being an outsider and worked as a waitress, supporting Basquiat – they were barely 20 – while they lived together for a couple of years. He was incredibly prolific, creating something like 250 paintings and 500 drawings during that time. By his early 20s, through a combination of his surprising confidence and sheer audacity and nerve in putting himself forward and his hugely visible and original talent, he was showing in galleries and selling so much there were stashes of cash in his tiny apartment – and drugs. He was dead from a seemingly accidental overdose aged 27.

This blazing, doomed trajectory was charted in this BBC documentary. Basquiat’s posthumous fame means significant exhibitions – there's an outstanding show currently at the Barbican – and even more for the headlines. An auction record for his painting Untitled was set this past May of $110 million, naturally sold to a Japanese entrepreneur, and – gasp – it was the sixth most expensive painting, and most expensive American painting, ever sold at auction. Naturally this financial milestone was the climax of the programme.

The dollar signs distort the story, which was certainly dramatic enough. Basquiat lived dirt poor partly by choice, having pranked so much at school that his disciplinarian father threw him out. But success changed things and near the end of his life, he and his collaborator and mentor Andy Warhol came home to Brooklyn for dinner.

There was a telling assortment of vintage photographs and film of the artist, where Basquiat’s laconic answers or just plain refusal to answer anything at all made his public personality enigmatic, although it was obvious too that he was both social and a party animal when he wished. We glimpsed the basement studio under the Anina Nosei gallery which the gallery owner lent him for work, and where clients could also interact. There were interviews with his main dealers: Bruno Bishopsberger of Zurich, Anina Nosei who gave Basquiat his first New York show until Basquiat, growing slightly paranoid and convinced she was selling unfinished work, left her for another leading light, Mary Boone; and the ubiquitous Larry Gagosian (pictured below with a Basquiat painting), currently the art world colossus of today, who showed Basquiat in Los Angeles. Others were fellow artists and curators, djs and musicians.

His sisters described how he had been run over by a car when playing in the street, when only 7 or so; while in hospital his mother had given him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, which became a treasured possession and an inspiration. He went early and incessantly to museums, learning by looking, as he never had a formal art education. He was immensely knowledgeable about the art of the past and present, from Caravaggio to Jackson Pollock, and had been obsessed by drawing. His father had played music from classical to jazz: music was important to the artists and Basquiat had a band called Gray. Later on black music – bebop and jazz – was influential on the rhythm of his work.

The star though of this absorbing and thoughtful film was appropriately the work: montages of words, numbers, and figures cascading through space. Being black – and the looming spectre of death – underlie much of the work even when all dressed up in vibrant colour. There was a compelling portrait of Basquiat and Warhol, with whom he was later to collaborate, that he did in an hour or so the day they met in Warhol’s studio, and took back to give to Andy when still wet. But Basquiat was profoundly distressed when a critic called him Andy’s mascot.

The star though of this absorbing and thoughtful film was appropriately the work: montages of words, numbers, and figures cascading through space. Being black – and the looming spectre of death – underlie much of the work even when all dressed up in vibrant colour. There was a compelling portrait of Basquiat and Warhol, with whom he was later to collaborate, that he did in an hour or so the day they met in Warhol’s studio, and took back to give to Andy when still wet. But Basquiat was profoundly distressed when a critic called him Andy’s mascot.

There were the motifs of portraits and skulls, and a terrifying image of death riding a fragmented equine skeleton. Through it all ran a technicolour rage at the way blacks were treated, marginalised, persecuted, enslaved; and a dependence on a white audience for success. Gagosian referred several times to a racist edge in the way Basquiat was treated, giving the film an edgy contemporary relevance. The posthumous triumph is not enough.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Add comment