The Spy Who Went Into the Cold, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

The Spy Who Went Into the Cold, BBC Four

The Spy Who Went Into the Cold, BBC Four

Atmospheric Storyville documentary on Kim Philby chases shadows

How much time does anyone want to spend in the company of Kim Philby? BBC Four’s Storyville allotted him 75 minutes, which isn’t much to tell the story of a third man with two paymasters and four wives. And yet this portrait somehow contrived to outstay its welcome. This is not to come over all huffy Heffer about betrayal. It’s just that hunting for the real Philby is like wandering around a maze uncertain if you’re looking for the entrance or the exit.

A dense construct of false fronts and double lives, raffishly charming and impeccably English, Philby amounted in The Spy Who Went into the Cold to a slippery nullity. A line-up of white-haired buffers had a go at outlining some memories. These included journalists, biographers, diplomats, historians and other assorted spook fanciers such as Phillip Knightley and the splendid Chapman Pincher, all of them emitting a faintly preposterous whiff of Empire starch and Establishment dust. None could quite put their finger on him, let alone land a glove. But then exactly how do you describe a void?

The facts of Philby’s career as a traitor were swiftly ticked off. The war was done and dusted within 10 minutes, and Philby was off from 1949 in Washington DC until Burgess and Maclean defected two years later, resulting in his own precautionary dismissal from the service. George Carey’s film was mostly interested in the long decade in which Philby, officially in the clear, and fixed up as a journalist in Beirut by friends on the edges of MI6, drank away the afternoons and waited to be exposed. This was the seedy period the likes of John Julius Norwich recalled with a cut-glass glint of nostalgic longing.

The film trowelled on the atmos by wandering about the rackety old streets of Beirut, even retracing Philby’s footsteps as far as the flat in Moscow his cheerful widow Rufina still shares with his old copies of Dick Francis and PG Wodehouse. Carey was also properly interrogative about the whats and whens and hows of Philby’s eventual flit from under the quivering nostrils of MI6. In an eccentric sleuthing trip to the Royal Botanical Gardens, he established that Anthony Blunt’s arrival in Lebanon to look for a frog orchid must have been a cover, because frog orchids don’t grow there.

The film trowelled on the atmos by wandering about the rackety old streets of Beirut, even retracing Philby’s footsteps as far as the flat in Moscow his cheerful widow Rufina still shares with his old copies of Dick Francis and PG Wodehouse. Carey was also properly interrogative about the whats and whens and hows of Philby’s eventual flit from under the quivering nostrils of MI6. In an eccentric sleuthing trip to the Royal Botanical Gardens, he established that Anthony Blunt’s arrival in Lebanon to look for a frog orchid must have been a cover, because frog orchids don’t grow there.

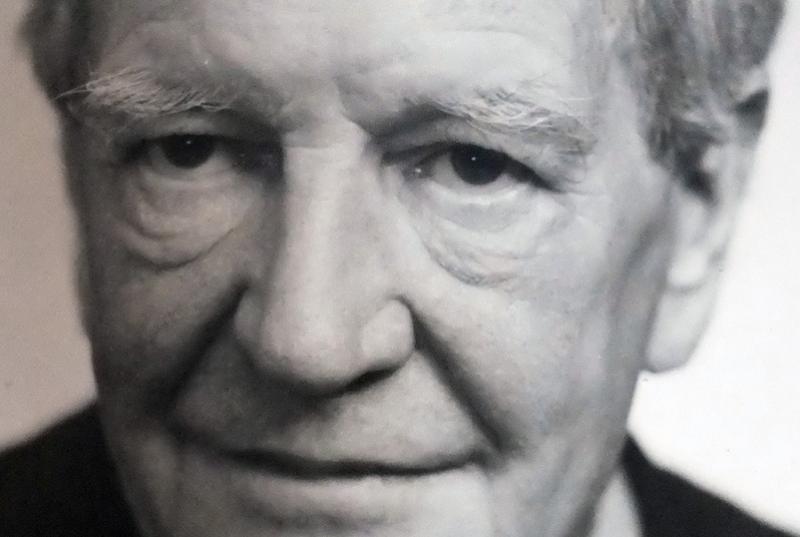

But other questions went unasked, mostly about the sheer selfishness and inhumanity necessary for the double life. Philby privatised betrayal in his first three marriages, leaving a succession of women to suffer the consequences of his ideological commitment. He makes Henry VIII looked like a shining light of uxoriousness. The last Mrs Philby (pictured above) recalled a pathetically insecure old man who hated to let her out of his sight: the traitor fearing betrayal, perhaps. Philby’s adoring daughter Josephine, whose lined face bears the distinctive imprint of her father’s suave features, seemed not to know much about him beyond the shadow of his absence. “Dad was all over the place,” she recalled. “We never really knew what he was doing.” You craved more on this, and yet it’s clear why this couldn’t be a longer film. With Kim Philby, more would be only less.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Your Friends & Neighbors, Apple TV+ review - in every dream home a heartache

Jon Hamm finds his best role since 'Mad Men'

Your Friends & Neighbors, Apple TV+ review - in every dream home a heartache

Jon Hamm finds his best role since 'Mad Men'

MobLand, Paramount+ review - more guns, goons and gangsters from Guy Ritchie

High-powered cast impersonates the larcenous Harrigan dynasty

MobLand, Paramount+ review - more guns, goons and gangsters from Guy Ritchie

High-powered cast impersonates the larcenous Harrigan dynasty

This City is Ours, BBC One review - civil war rocks family cocaine racket

Terrific cast powers Stephen Butchard's Liverpool drug-ring saga

This City is Ours, BBC One review - civil war rocks family cocaine racket

Terrific cast powers Stephen Butchard's Liverpool drug-ring saga

The Potato Lab, Netflix review - a K-drama with heart and wit

Love among Korean potato-researchers is surprisingly funny and ideal for Janeites

The Potato Lab, Netflix review - a K-drama with heart and wit

Love among Korean potato-researchers is surprisingly funny and ideal for Janeites

Adolescence, Netflix review - Stephen Graham battles the phantom menace of the internet

How antisocial networks lead to real-life tragedy

Adolescence, Netflix review - Stephen Graham battles the phantom menace of the internet

How antisocial networks lead to real-life tragedy

Drive to Survive, Season 7, Netflix review - speed, scandal and skulduggery in the pitlane

The F1 documentary series is back on the pace

Drive to Survive, Season 7, Netflix review - speed, scandal and skulduggery in the pitlane

The F1 documentary series is back on the pace

A Cruel Love: The Ruth Ellis Story, ITV1 review - powerful dramatisation of the 1955 case that shocked the public

Lucy Boynton excels as the last woman to be executed in Britain

A Cruel Love: The Ruth Ellis Story, ITV1 review - powerful dramatisation of the 1955 case that shocked the public

Lucy Boynton excels as the last woman to be executed in Britain

Towards Zero, BBC One review - more entertaining parlour game than crime thriller

The latest Agatha Christie adaptation is well cast and lavishly done but a tad too sedate

Towards Zero, BBC One review - more entertaining parlour game than crime thriller

The latest Agatha Christie adaptation is well cast and lavishly done but a tad too sedate

Bergerac, U&Drama review - the Jersey 'tec is born again after 34 years

Damien Molony boldly follows in the hallowed footsteps of John Nettles

Bergerac, U&Drama review - the Jersey 'tec is born again after 34 years

Damien Molony boldly follows in the hallowed footsteps of John Nettles

A Thousand Blows, Disney+ review - Peaky Blinders comes to Ripper Street?

The prolific Steven Knight takes us back to a squalid Victorian London

A Thousand Blows, Disney+ review - Peaky Blinders comes to Ripper Street?

The prolific Steven Knight takes us back to a squalid Victorian London

Zero Day, Netflix review - can ex-President Robert De Niro save the Land of the Free?

Panic and paranoia run amok as cyber-hackers wreak havoc

Zero Day, Netflix review - can ex-President Robert De Niro save the Land of the Free?

Panic and paranoia run amok as cyber-hackers wreak havoc

The White Lotus, Series 3, Sky Atlantic review - hit formula with few surprises but a new bewitching soundtrack

Thailand hosts the latest bout of Mike White's satirical takedown of the rich and privileged

The White Lotus, Series 3, Sky Atlantic review - hit formula with few surprises but a new bewitching soundtrack

Thailand hosts the latest bout of Mike White's satirical takedown of the rich and privileged

Add comment