Warren Mitchell - ‘If you could be Welsh and Jewish you really couldn’t miss’ | reviews, news & interviews

Warren Mitchell - ‘If you could be Welsh and Jewish you really couldn’t miss’

Warren Mitchell - ‘If you could be Welsh and Jewish you really couldn’t miss’

The creator of Alf Garnett, and Arthur Miller’s favourite British actor, remembered

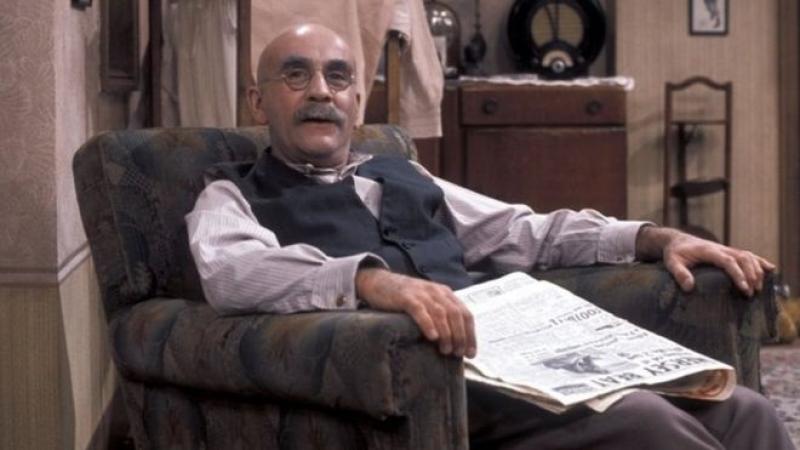

“He has been in poor health for some time, but was cracking jokes to the last,” read the statement from Warren Mitchell’s family following news of his death today, at the age of 89. That will come as no surprise for those who remember the actor primarily as Alf Garnett, first in Till Death Do Us Part (on the BBC, 1965-75), and later In Sickness and In Health (1985-1992).

But, as I discovered when interviewing Mitchell in 2002 on the eve of his playing the lead in Arthur Miller’s The Price, there was much more to him than the Cockney dock-worker. He was Miller’s favourite British actor, and won Olivier Awards in 1979 for Death of a Salesman and 2004 for The Price.

WOULD WARREN MITCHELL be taken more seriously as an actor if he’d kept his original name? The name his grandparents brought over from the Russian shtetl nearly 100 years ago was Misell (pronounced my-zell).

“The little work I had, they never pronounced it right, they never spelt it right,” he says. “Then I went to Radio Luxembourg as a disc jockey as a relief for Pete Murray.

“They said, ‘You can’t have a name like that, nobody’s ever going to write in their request to Warren Misell.’ So I changed it to Mitchell. When I came home, I went back to Misell. Then I was doing cabaret and we were introduced by a gorgeous lady in rhyming couplets and she couldn’t find a rhyme for Misell. So I went back to Mitchell.” (Below, with Dandy Nichols as Alf's long-suffering wife Else.)

It’s the Warren Misell in him, you suspect, that makes Mitchell Arthur Miller’s favourite British actor. He has played Willy Loman from Death of a Salesman no fewer than four times, twice here, twice in Australia. He is now having his second stab at Solomon Gregory, a Methuselah-like furniture dealer who finds himself at the centre of another family’s private war in The Price. When Mr Peter’s Confessions had its world premiere at the Almeida, Miller wanted Mitchell to play the lead.

It’s the Warren Misell in him, you suspect, that makes Mitchell Arthur Miller’s favourite British actor. He has played Willy Loman from Death of a Salesman no fewer than four times, twice here, twice in Australia. He is now having his second stab at Solomon Gregory, a Methuselah-like furniture dealer who finds himself at the centre of another family’s private war in The Price. When Mr Peter’s Confessions had its world premiere at the Almeida, Miller wanted Mitchell to play the lead.

“It was a strange piece. When Miller himself asks for you, you think, I can’t fuck about with Arthur, but I couldn’t understand it, so I turned it down.” Then, when Miller was recently given the freedom of Norwich, it was Mitchell who was invited to give the address.

“I told this anecdote about when I was doing Death of a Salesman at the National. I was laying some paving stones in the garden and this stonemason leaned across the fence and said, ‘Oi, Alf, you’re doin’ that all wrong.’ He came over and showed me how to do it. In the mood of bringing culture to the masses, I said, ‘Would you like to be my guest at this play?’ He said, ‘Oh yeah, whassat, Alf? We like to go out Friday night, we go out the dogs normally.’ After the show, I met him in the green room and for 10 minutes he didn’t mention the play. We spoke about darts, football, politics, everything. He finally leant across the table and said, ‘It’s a bit ‘ard on the bum, innit.’ ‘You see, Arthur,’ I said, ‘you thought you wrote a masterpiece. Not for this geezer you didn’t.’”

America’s greatest living playwright, you suspect, is barely aware of Alf Garnett, the wellspring of Mitchell’s celebrity. Mitchell recalls Miller coming to talk to the Salesman cast at the National: “He said, ‘You know when we went on tour with the play, the management wanted to change the title. They said, it’s death, it really is death to have the word death in the title. They came up with all sorts of other suggestions.’ Then he asked us, ‘What would you think would be an alternative title?’ And somebody in the cast said, ‘What about Till Death Us Do Part?’” Miller didn’t know why everyone was laughing. (Mitchell as Willy Loman at the National Theatre, 1980, by Reg Wilson.)

America’s greatest living playwright, you suspect, is barely aware of Alf Garnett, the wellspring of Mitchell’s celebrity. Mitchell recalls Miller coming to talk to the Salesman cast at the National: “He said, ‘You know when we went on tour with the play, the management wanted to change the title. They said, it’s death, it really is death to have the word death in the title. They came up with all sorts of other suggestions.’ Then he asked us, ‘What would you think would be an alternative title?’ And somebody in the cast said, ‘What about Till Death Us Do Part?’” Miller didn’t know why everyone was laughing. (Mitchell as Willy Loman at the National Theatre, 1980, by Reg Wilson.)

Mitchell, at 76, is not as busy as he used to be. “When you get to 76, your phone doesn’t ring that much. The dear Roy Kinnear said, ‘You don’t retire in our business, you just notice the phone hasn’t rung for 10 years.’ I had an agent many years ago who said, ‘When you’re out of work, Warren, it’s better to walk up and down Piccadilly than sit in your garden. You may meet somebody who may think of you for a play.’” Sure enough, Mitchell had been a bit low when he went to see a play at the Tricycle last winter. The day after, the theatre’s artistic director phoned Mitchell’s agent and offered him The Price.

Miller wrote a sweet letter back saying, ‘I’m glad to see you’re big in Kirribilli, Warren’

He first played Solomon Gregory last year in the Ensemble Theatre in Sydney, which has become a second home professionally. In that production, his son Daniel played one of the estranged brothers flogging off an old houseful of bric-a-brac. “I sent Arthur the notices from Sydney, which were raves. He wrote a sweet letter back saying, ‘I’m glad to see you’re big in Kirribilli, Warren.’” He’s now an Australian citizen. “I’ve sort of fallen in love with the place. I’d love to live there, but my wife is not so keen, because of the dog.”

Miller wrote the play in 1968 to memorialise a Russian-Jewish version of English speech that even then was dying. “It doesn’t exist any more,” says Mitchell, “like my Jewish grandmother spoke. She started a fish and chip shop in Stoke Newington High Road. ‘When business is good, Warren, people eat fish and chips. When business is bad, people eat fish and chips. Start a fish and chip shop, never go hungry.’ That’s the sound of this play.”

Mitchell does a bewildering array of Jewish accents, and a beautiful Welsh one. He was partly inspired to become an actor by meeting Richard Burton when they were both RAF cadets at Oxford in the war. He even did a Welsh character for his Rada audition. “I always thought if you could be Welsh and Jewish you really couldn’t miss. We all thought Richard should have been the governor. He should have been the new Olivier. He had that talent and he was absolute magic. But he wanted the dosh and the birds, and he got them both.” He also acted with the young Mel Gibson in the Sydney incarnation of Death of a Salesman. I ask him for a comparison between the two film stars. “There is no comparison,” he says.

Mitchell first played Alf Garnett in 1965, after Peter Sellers, Lionel Jeffries and Leo McKern had turned it down. His agent thought he shouldn’t do more than one series. These days he still wheels him out for his one-man show and he hasn’t entirely given up hope that some enterprising young buck will get Johnny Speight’s final Garnett script off the ground, in which the Right-wing Alf discovers that his long-lost grandson is the Labour Prime Minister.

Mitchell first played Alf Garnett in 1965, after Peter Sellers, Lionel Jeffries and Leo McKern had turned it down. His agent thought he shouldn’t do more than one series. These days he still wheels him out for his one-man show and he hasn’t entirely given up hope that some enterprising young buck will get Johnny Speight’s final Garnett script off the ground, in which the Right-wing Alf discovers that his long-lost grandson is the Labour Prime Minister.

Any resemblance to Tony Booth, who played Alf’s son-in-law, and his relationship with his own son-in-law is entirely uncoincidental. “Tony and I didn’t get on all that well in the series. We had arguments. But you get together and forget the past. Una [Stubbs] and Tony would be very happy to come back and play their old parts. There is a lot of mileage there. In the script, the Tories are deliberately giving Alf functions to go to in order to embarrass the Labour government.” (Above, with Una Stubbs as daughter Rita and Tony Booth as son-in-law Mike.)

I ask Mitchell if there is a corollary between the actor who never retires and old Solomon who, at 89, still can’t resist the cut and thrust of the deal. “Very much so, yes. Absolutely,” he says. “I don’t enjoy the prospect of retirement. I’m not very good at anything else. I do gardening, I do sailing, I do fathering and grandfathering, but I don’t do them particularly well. I’ve been married for 51 years to the same lady. And I’m not very good at it.”

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

MobLand, Paramount+ review - more guns, goons and gangsters from Guy Ritchie

High-powered cast impersonates the larcenous Harrigan dynasty

MobLand, Paramount+ review - more guns, goons and gangsters from Guy Ritchie

High-powered cast impersonates the larcenous Harrigan dynasty

This City is Ours, BBC One review - civil war rocks family cocaine racket

Terrific cast powers Stephen Butchard's Liverpool drug-ring saga

This City is Ours, BBC One review - civil war rocks family cocaine racket

Terrific cast powers Stephen Butchard's Liverpool drug-ring saga

The Potato Lab, Netflix review - a K-drama with heart and wit

Love among Korean potato-researchers is surprisingly funny and ideal for Janeites

The Potato Lab, Netflix review - a K-drama with heart and wit

Love among Korean potato-researchers is surprisingly funny and ideal for Janeites

Adolescence, Netflix review - Stephen Graham battles the phantom menace of the internet

How antisocial networks lead to real-life tragedy

Adolescence, Netflix review - Stephen Graham battles the phantom menace of the internet

How antisocial networks lead to real-life tragedy

Drive to Survive, Season 7, Netflix review - speed, scandal and skulduggery in the pitlane

The F1 documentary series is back on the pace

Drive to Survive, Season 7, Netflix review - speed, scandal and skulduggery in the pitlane

The F1 documentary series is back on the pace

A Cruel Love: The Ruth Ellis Story, ITV1 review - powerful dramatisation of the 1955 case that shocked the public

Lucy Boynton excels as the last woman to be executed in Britain

A Cruel Love: The Ruth Ellis Story, ITV1 review - powerful dramatisation of the 1955 case that shocked the public

Lucy Boynton excels as the last woman to be executed in Britain

Towards Zero, BBC One review - more entertaining parlour game than crime thriller

The latest Agatha Christie adaptation is well cast and lavishly done but a tad too sedate

Towards Zero, BBC One review - more entertaining parlour game than crime thriller

The latest Agatha Christie adaptation is well cast and lavishly done but a tad too sedate

Bergerac, U&Drama review - the Jersey 'tec is born again after 34 years

Damien Molony boldly follows in the hallowed footsteps of John Nettles

Bergerac, U&Drama review - the Jersey 'tec is born again after 34 years

Damien Molony boldly follows in the hallowed footsteps of John Nettles

A Thousand Blows, Disney+ review - Peaky Blinders comes to Ripper Street?

The prolific Steven Knight takes us back to a squalid Victorian London

A Thousand Blows, Disney+ review - Peaky Blinders comes to Ripper Street?

The prolific Steven Knight takes us back to a squalid Victorian London

Zero Day, Netflix review - can ex-President Robert De Niro save the Land of the Free?

Panic and paranoia run amok as cyber-hackers wreak havoc

Zero Day, Netflix review - can ex-President Robert De Niro save the Land of the Free?

Panic and paranoia run amok as cyber-hackers wreak havoc

The White Lotus, Series 3, Sky Atlantic review - hit formula with few surprises but a new bewitching soundtrack

Thailand hosts the latest bout of Mike White's satirical takedown of the rich and privileged

The White Lotus, Series 3, Sky Atlantic review - hit formula with few surprises but a new bewitching soundtrack

Thailand hosts the latest bout of Mike White's satirical takedown of the rich and privileged

Hacks, Season 3, NOW review - acerbic showbiz comedy keeps up the good work

Jean Smart's portrayal of Deborah Vance is an all-time classic

Hacks, Season 3, NOW review - acerbic showbiz comedy keeps up the good work

Jean Smart's portrayal of Deborah Vance is an all-time classic

Add comment