Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, Victoria & Albert Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, Victoria & Albert Museum

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, Victoria & Albert Museum

A romantic 'hero-artist' or just a designer with a melancholic imagination?

Alexander McQueen designed some dresses to die for. Dominating a wood-panelled room dedicated to Romantic Nationalism, in acknowledgement of his Scottish origins, is a crimson cape worn over a simple white dress. The high collar, puffed sleeves and long train lend the shimmering red taffeta a baronial splendour perfect for dramatic entrances.

Nearby is a white tulle dress whose bodice is encrusted with tiny red beads, worn beneath a red silk taffeta jacket layered into exaggerated folds reminiscent of coral. One could imagine sporting these garments with great pleasure, knowing that they made you look a million dollars.

Visual impact often took precedence over wearability, though, and most of McQueen’s creations are closer to theatrical costumes or props than to clothing. Take for example his dress and cap made of red feathers, whose frothy white underside is revealed only at the back. Reminiscent of a tutu, it could be a costume for a far-out performance of Swan Lake.

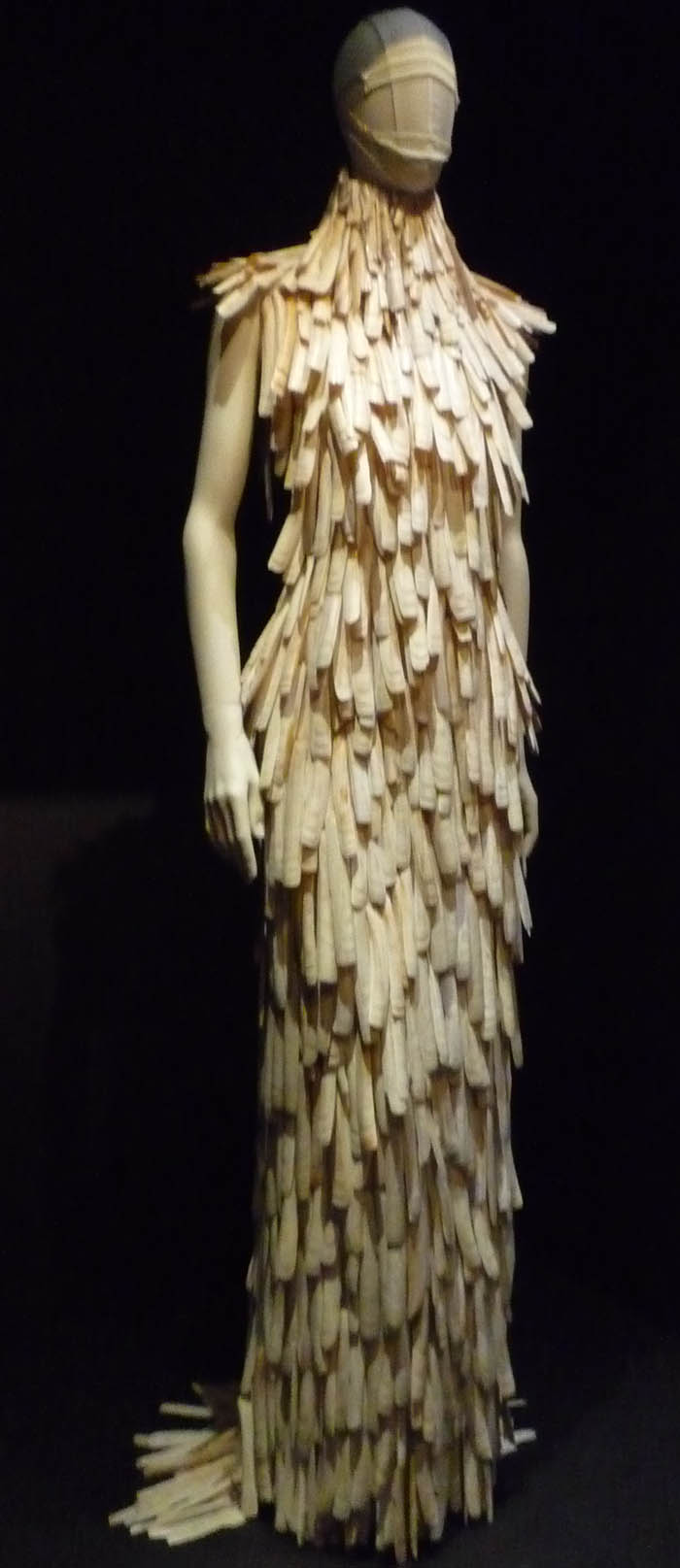

In 1999 he designed a skirt and winged jacket from perforated plywood. Named after a Yoruba deity, his Eshu collection of 2000 included a black coat made of rope-like coils of synthetic hair that engulfed the wearer like a monstrous wig. The following year, the Voss collection featured a slender sheath of razor clam shells (pictured left) and a full skirt made from polished oyster shells.

In 1999 he designed a skirt and winged jacket from perforated plywood. Named after a Yoruba deity, his Eshu collection of 2000 included a black coat made of rope-like coils of synthetic hair that engulfed the wearer like a monstrous wig. The following year, the Voss collection featured a slender sheath of razor clam shells (pictured left) and a full skirt made from polished oyster shells.

What makes these garments such fun, of course, is their implausibility. Rather than enhancing the wearer’s appearance or experience, they are meant to be admired in and for themselves; models become little more than mobile coat hangers whose function is to display goods that are more desirable as objects than as clothing.

How, then, to think of McQueen? He described himself as a “romantic schizophrenic” and the introductory spiel proclaims him a “hero-artist” on a par with the poets and painters of the Romantic Movement. “Evoking the sensations of shock and awe associated with the sublime,” we are told, “his dark imaginings elicited an uneasy pleasure that merged wonder and terror, incredulity and revulsion. Like an artist of the Romantic Movement, unfettered emotionalism sustained his profound appreciation of beauty.”

Why does such absurdly overblown rhetoric accrue around fashion design? Had McQueen been a costume or set designer would such exaggerated claims be made on his behalf? I doubt it. And it encourages cynicism, which is a shame, since he was wonderfully inventive and the exhibition is extremely enjoyable, despite the hype.

McQueen approached his catwalk shows as performances. In Its Only a Game 2005, models enacted a game of chess on a giant board; in Voss (2001), they were incarcerated in a mirrored cube; Joan (1998) climaxed with a model encircled by a ring of fire; No 13 (1999) ends with two robots spray-painting the white dress worn by ballerina Shalom Harlow (pictured below), while The Widows of Culloden (2006) ended with a smoke-and-mirrors image of Kate Moss floating like a spectre in a layered dress of frothy white tulle. Captured on video, most are displayed in the central space as The Cabinet of Curiosities, while in a large glass box nearby, Kate Moss hovers theatrically, like the ghost of Miss Havisham.

McQueen was an insatiable scavenger, borrowing ideas from as far afield as India, China, Russia, America and Africa, not to mention Tudor England, and mixing them in unlikely combinations. One outfit for It's Only a Game consists of a kimono-style sash worn over embroidered shorts with a fibreglass helmet and epaulettes, like those worn by American footballers. The clash of East meets West doesn’t quite gel, but the chutzpah is refreshing nonetheless.

McQueen was an insatiable scavenger, borrowing ideas from as far afield as India, China, Russia, America and Africa, not to mention Tudor England, and mixing them in unlikely combinations. One outfit for It's Only a Game consists of a kimono-style sash worn over embroidered shorts with a fibreglass helmet and epaulettes, like those worn by American footballers. The clash of East meets West doesn’t quite gel, but the chutzpah is refreshing nonetheless.

The accessories are the most inventive aspects of the designs, though. Most were created in collaboration with milliner Philip Treacy or jewellery designer Shaun Leane. Among the most outlandish are headdresses consisting, variously, of a set of antlers and Thomson’s gazelle horns, a bird skull adorned with bird of paradise feathers, a silver bird’s nest full of jewelled eggs beneath outspread mallard wings and a butterfly headdress made from turkey feathers painted to resemble a swarm of red admirals (pictured above right).

The metal jewellery often resembles instruments of torture, whether it be a twisted spine supported by aluminium ribs, a nest of spikes enfolding a face, or a collar of silver branches bearing “grapes” of Tahitian pearls (pictured left). The shoes look downright dangerous. The platforms that gave Chinese emperors added height and raised Elizabethan dignitaries above the filth of London’s streets were an ongoing source of inspiration. Those worn by McQueen’s Aliens in 2010 were 3D printed in white resin with elaborate furls reminiscent of baroque sculpture. Refusing to wear his infamous Armadillo shoes, three models quit his 2010 runway show, which was to be the last before McQueen's suicide at only 40. Looking more like hooves than shoes, they tip the wearer’s balance unnaturally forwards.

The metal jewellery often resembles instruments of torture, whether it be a twisted spine supported by aluminium ribs, a nest of spikes enfolding a face, or a collar of silver branches bearing “grapes” of Tahitian pearls (pictured left). The shoes look downright dangerous. The platforms that gave Chinese emperors added height and raised Elizabethan dignitaries above the filth of London’s streets were an ongoing source of inspiration. Those worn by McQueen’s Aliens in 2010 were 3D printed in white resin with elaborate furls reminiscent of baroque sculpture. Refusing to wear his infamous Armadillo shoes, three models quit his 2010 runway show, which was to be the last before McQueen's suicide at only 40. Looking more like hooves than shoes, they tip the wearer’s balance unnaturally forwards.

"I find beauty in the grotesque," claimed McQueen. “There has to be a sinister aspect whether it's melancholy or sadomasochistic... like a masquerade.” Catwalk fashion is often excused as harmless fantasy and McQueen’s designs frequently resemble carnival dress or theatrical costumes. But watching a bunch of teenage girls at the weekend tottering over cobblestones in five-inch heels, I couldn’t help pondering the trickle-down effect of these spectacles. The implicit sadomasochism of many of McQueen’s designs reinforces the equation between glamour and pain; the wearer is subservient to the design, rather than the other way round. Women are designated as fashion victims rather than conquerors, which makes me deeply ambivalent about his ideas. His designs are great fun, provided you ignore their implications.

Overleaf: watch a video of McQueen's runway shows and the exhibition display

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Comments

Interesting you mention