Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery

Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery

A rich survey of the Berlin Dada artist may also make you recoil over some of its imagery

What once appeared daring and transgressive will often barely raise an eyebrow given time. This much is obvious – or at least up to a point, since much avant-garde art continues to challenge and/or bemuse well into the 21st century. But the reverse can also be true. What was once produced as a work typical of its time can now make us feel very uncomfortable.

Hannah Höch was a member of Berlin Dada in the years immediately following the First World War. These were the Weimar years in which artists who were later denounced as degenerate by the Nazi regime produced scabrous attacks on bourgeois values and the political elite who had been guilty of so much destruction. Along with John Heartfield and Kurt Schwitters, Höch helped establish the art of photomontage and collage as a serious art form. Schwitters, she later said, was one of only two male artists to take her seriously as a woman; the other was Hans Arp. She also painted and made woodcuts throughout her long life (she died aged 88 in 1978). But it’s for her cut-and-paste work of the Twenties and Thirties for which she is best remembered.

The piece feels at best ambivalent or, rather, simply confused

As a Dada artist living through the aftermath of war and in a climate of alarming hyper-inflation, she, like her peers, attacked the usual suspects: financiers and politicians. But, conscious of her sex and no doubt her bisexuality (in photographs, she looks the very model of the New Woman and one can imagine her painted by Otto Dix, in the style of his Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden), Höch additionally confronted issues of gender.

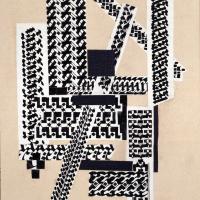

She produced hybrid male/female caricatures: middle-aged male heads appear on female bodies with ballerina legs or stiletto-clad feet. And she delights in switching traditional gender roles. In The Father, 1920, a male head is stuck on a female body cradling a baby. Framing the father/mother figure, which is itself set against a vortex of modernist forms and typography, are athletic female bodies in mid-movement. But one athletic figure is set apart from the rest – a brawny male boxer is planting a well-aimed fist at the swaddled infant’s face. The infant’s enlarged eye may or may not be the result of impact.

In fact, enlarged eyes are a favoured motif, creating a comic sense of bathos, such as we find in The Melancholic, 1925, or the theatrical The Tragedienne, 1924, in which a huge disembodied hand mimics a melodramatic clasp of the breast. And so too are those female legs, athletic as well as balletic, a nod to the era’s new-found fascination with the classical streamlined body and whose inclusion also adds a formal rhythmic dynamism to the work.

Racial identities are also mined for visual impact, and there are arresting images of hybrid ethnicities (a cut-and-paste miscegenation as white European and African features redraw the map of the racially pure face). But this is where the avant-garde transgression comes back to haunt us. How should we really read a work such as Peasant Couple, 1931, in which we find two heads, a black man in a hat (a German colonial hat?) and an ape in blonde plaits. The two heads float above truncated legs affixed to no body, so they are doubly freakish – boots and jodhpurs for the man, dolly shoes and white ankle socks for the grotesque apparition of the ape “woman”. It surely shocks us more today than it ever did when it was made, and the piece feels at best ambivalent or, rather, simply confused. It would feel like an embarrassed hush not to note the problematic nature of this image (unfortunately, I'm barred from using the image in association with this exhibition - you can view it here in black and white).

Some of this, incidentally, might also be said for Love in the Bush, 1925, in which a black boy attempts to embrace a white women with long swinging arms and huge white-gloved "black minstrel" hands, but, in fact, she treats the white woman similiarly, or at least the woman has one of those strange, long arms.

I think one may confidently say that Höch was not a particularly sophisticated, or always coherent, agit-prop artist. She didn't have that sharply defined and incisive vision that make the images of her fellow photomontage pioneer John Heartfield such powerful and enduring satires. That was never her strong suit. Her interests lay primarily in form, and this was sometimes, not always successfully, aligned to political matters. The irony is, these are the works that interest us most. Just read the publicity material for the exhibition. This is what is pushed to the forefront, as if she were a kind of visual Bertolt Brecht. (That said, her most famous, and one of her most visually successful collages in this vein, the 1919 Cut with the Kitchen Knife: Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, is actually not in the exhibition.) Furthermore, I’m not entirely convinced that the sole reason she was apparently neglected by art history was on the grounds she was a woman, which is a line I keep reading, and is always the same kneejerk line with any forgotten female artist. Whether she was sidelined at the time (though by all acounts her work was a critical hit at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920) she was certainly rediscovered before she died, with major exhibitions in Paris and Berlin, as well as being featured in many exhibitions during her lifetime, including a Dada and Surrealism exhibition at MOMA in 1936. Her friend Schwitters was the Berlin Dadaist who died in obscurity (though here I would say Höch is the greater talent). And how many now have heard of her former lover Raoul Hausmann, who was at the centre of Berlin Dada and whose portrait of Höch can be found in this exhibition?

Furthermore, I’m not entirely convinced that the sole reason she was apparently neglected by art history was on the grounds she was a woman, which is a line I keep reading, and is always the same kneejerk line with any forgotten female artist. Whether she was sidelined at the time (though by all acounts her work was a critical hit at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920) she was certainly rediscovered before she died, with major exhibitions in Paris and Berlin, as well as being featured in many exhibitions during her lifetime, including a Dada and Surrealism exhibition at MOMA in 1936. Her friend Schwitters was the Berlin Dadaist who died in obscurity (though here I would say Höch is the greater talent). And how many now have heard of her former lover Raoul Hausmann, who was at the centre of Berlin Dada and whose portrait of Höch can be found in this exhibition?

In art nearly everyone is forgotten but the few, including those who may have had great acclaim during their active years. What's more, Höch lived a very quiet life on the outskirts of Berlin for many years from the Thirties, with the rise of the Nazies, until her death. Gender is only one of many factors that come into play, though you often wouldn't think so. And if she was neglected for being a woman, there are always those who will argue she is only being given renewed attention for being one, too. In the end one has only the work to go on, and her best work still speaks to us with vigour and relevance. (Picture above right: Fashion Show, 1925-35 [detail]; Landesmuseum of Modern Art)

This exhibition spans the length of Höch’s career, with over 100 works (though only a very tiny selection of paintings). We see that she eventually forgoes figurative collage with their nod to identity politics and moves into abstraction, though figurative motifs continue, on and off, to inform her work. These may not always be as interesting to us today but perhaps, having begun her career as a brilliant textile designer, this is where she always felt more at ease as an artist.

Gallery: Click image below to enter gallery

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Add comment