John Deakin and the Lure of Soho, Photographers' Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

John Deakin and the Lure of Soho, Photographers' Gallery

John Deakin and the Lure of Soho, Photographers' Gallery

The chronicler of bohemian London is revealed as a mass of contradictions

John Deakin was lukewarm about his career as a photographer because his heart wasn’t in it. Really, he wanted to be a painter, and so it was in spite of himself that he became a staff photographer at Vogue in 1947, acquiring a reputation for innovative portraiture and fashion work.

The tension between Deakin’s life as a talented, salaried photographer, and his role at the heart of London’s bohemian underbelly is the premise of this exhibition, which brings together his photographs of Soho streetlife, portraits of his friends, and examples of his fashion work and paintings.

Like many truly great fashion shots, it is about so much more than clothes

Deakin’s pictures of tradesmen and other Soho faces have the assuredness that comes from operating on one’s own turf, and they hover somewhere between formal portraiture and reportage. Tony Abbro, Abbro and Varriano, newsagents, Dean Street, Soho, 1961, is of a man clearly resistant to having his picture taken, yet Deakin has coaxed him outside to pose with his racks of newspapers and magazines. In his shot of an ice seller, Deakin has allowed his subject’s head to almost fill the frame, emphasising the size of the great rock of ice he has on his shoulder, and injecting energy and movement. The man’s glance to the camera suggests that Deakin would have gone unnoticed altogether had his subject not had to squeeze past him through the shop door. A more contemplative mood imbues the portrait of writer Eileen Bigland, sitting alone at a table in the still after hours.

Frankly, these Soho portraits are a puzzle. They are often thoughtful, sympathetic even, suggesting a photographer of substance and subtlety, at odds with Deakin’s reputation as unpleasant to the point of demonic. The exhibition rather revels in tales of his nastiness, and several well-worn anecdotes are recounted, including heiress Barbara Hutton’s comment that Deakin was the “second nastiest little man I have ever met”, apparently leaving his Soho acquaintances wondering who on earth could have been nastier.

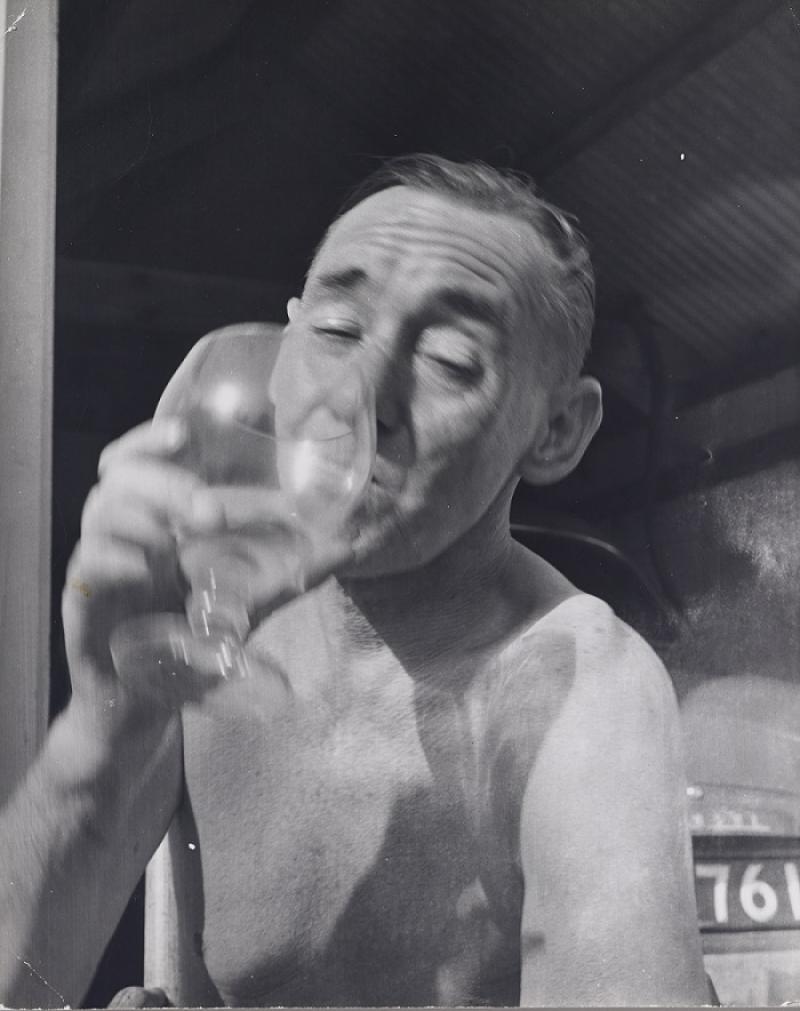

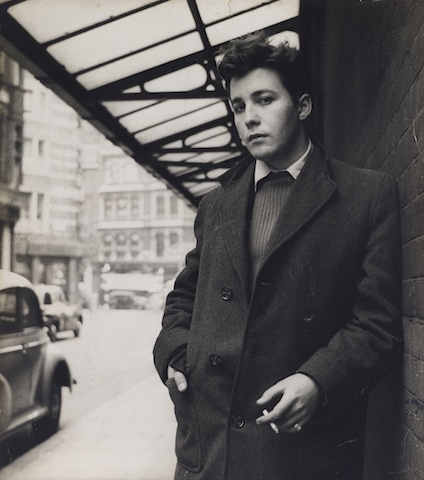

Paradoxically, it is in his portraits of his friends, the ragtag bunch of the talented and the not so, muses, lovers and hangers-on, that Deakin’s eye hardens. Francis Bacon stares out cold and impassive, the camera angled upwards to distort his face, while a young Jeffrey Bernard (pictured right) shrinks from the camera. In a blurred picture of himself, taken, by the looks of it, some way into a drinking session (main picture), Deakin is shirtless and squinting blindly at either the camera or the near empty glass in his hand, every inch the morose drunk.

Paradoxically, it is in his portraits of his friends, the ragtag bunch of the talented and the not so, muses, lovers and hangers-on, that Deakin’s eye hardens. Francis Bacon stares out cold and impassive, the camera angled upwards to distort his face, while a young Jeffrey Bernard (pictured right) shrinks from the camera. In a blurred picture of himself, taken, by the looks of it, some way into a drinking session (main picture), Deakin is shirtless and squinting blindly at either the camera or the near empty glass in his hand, every inch the morose drunk.

While so many of his pictures exude a withering toxicity, the exhibition offers a tantalizing glimpse of Deakin’s exquisite fashion work. In a shot from 1947, an immaculately dressed woman in a fur coat walks towards the camera; the very essence of sang froid, she is dwarfed by the towering remains of a bombed building, and yet our eyes are drawn to her, a beacon of serenity in a scene of devastation. Like many truly great fashion shots, it is about so much more than clothes.

For all the contradictions revealed in his photographs, the few paintings on display here further muddy the waters. Painstakingly done, colourful and naïve, their hopeful innocence borders on the embarrassing. Deakin’s Soho friends were a notoriously acid, sarcastic bunch, and the prospect of their censure must have been excruciating, and yet Deakin was sufficiently committed to painting that he even produced two portraits of Bacon.

Bacon himself seems to have resisted commenting on Deakin’s paintings, but called his photographs “the best since Nadar and Julia Margaret Cameron”, commissioning Deakin to photograph a number of his subjects, from which, as was his method, he would paint. But their relationship must have been far from equal, with Deakin apparently in thrall to Bacon. Deakin’s characterisation of his sitters as his “victims” echoes, and seems to emulate, Bacon’s comment to critic David Sylvester that he preferred not to work from life because he did not want to “practise before them the injury that I do to them in my work”. Bacon regarded Deakin as a great photographer, but as he seems to have regarded photography as largely utilitarian, a convenient form of source material, this is perhaps less of a compliment than it might at first appear.

Certainly, there is plenty of room to speculate that Deakin was plagued by a sense of inadequacy and for evidence of his neglect of his own work and indeed reputation, we need look no further than the prints in this exhibition. Dog-eared and torn, they were found in boxes in his flat after he died, the modest but wonderful remains of Soho’s greatest chronicler.

- John Deakin and the Lure of Soho at the Photographers' Gallery until 13 July

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit, Tate Modern review - adolescent angst indefinitely extended

The artist who refused to grow up

Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit, Tate Modern review - adolescent angst indefinitely extended

The artist who refused to grow up

Monet and London, Courtauld Gallery review - utterly sublime smog

Never has pollution looked so compellingly beautiful

Monet and London, Courtauld Gallery review - utterly sublime smog

Never has pollution looked so compellingly beautiful

Michael Craig-Martin, Royal Academy review - from clever conceptual art to digital decor

A career in art that starts high and ends low

Michael Craig-Martin, Royal Academy review - from clever conceptual art to digital decor

A career in art that starts high and ends low

Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, National Gallery review - passions translated into paint

Turmoil made manifest

Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, National Gallery review - passions translated into paint

Turmoil made manifest

Peter Kennard: Archive of Dissent, Whitechapel Gallery review - photomontages sizzling with rage

Fifty years of political protest by a master craftsman

Peter Kennard: Archive of Dissent, Whitechapel Gallery review - photomontages sizzling with rage

Fifty years of political protest by a master craftsman

Dominique White: Deadweight, Whitechapel Gallery review - sculptures that seem freighted with history

Dunked in the sea to give them a patina of age, sculptures that feel timeless

Dominique White: Deadweight, Whitechapel Gallery review - sculptures that seem freighted with history

Dunked in the sea to give them a patina of age, sculptures that feel timeless

Comments

Abbro and Varriano Newsagents