Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed, Freud Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed, Freud Museum

Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed, Freud Museum

The artist's psychoanalytic writings frame works obsessed with psychic trauma

Louise Bourgeois tirelessly, obsessively documented her 32 years of psychoanalysis.

But since the discovery of her psychoanalytic writings (two boxes discovered in 2004, and two just after her death, aged 98, in 2010) some rather big claims have been made for them: they must surely take their place, says her literary executor Phillip Larratt-Smith, alongside the autobiography of Cellini, the journals of Delacroix and the letters of Van Gogh. Maybe so, and a two-volume monograph will shortly be published that contains a selection, but on the basis of what is featured at the Freud Museum, maybe not, and in any case, it’s rather difficult to read them all as they are presented here, on the walls and framed and placed in glass vitrines.

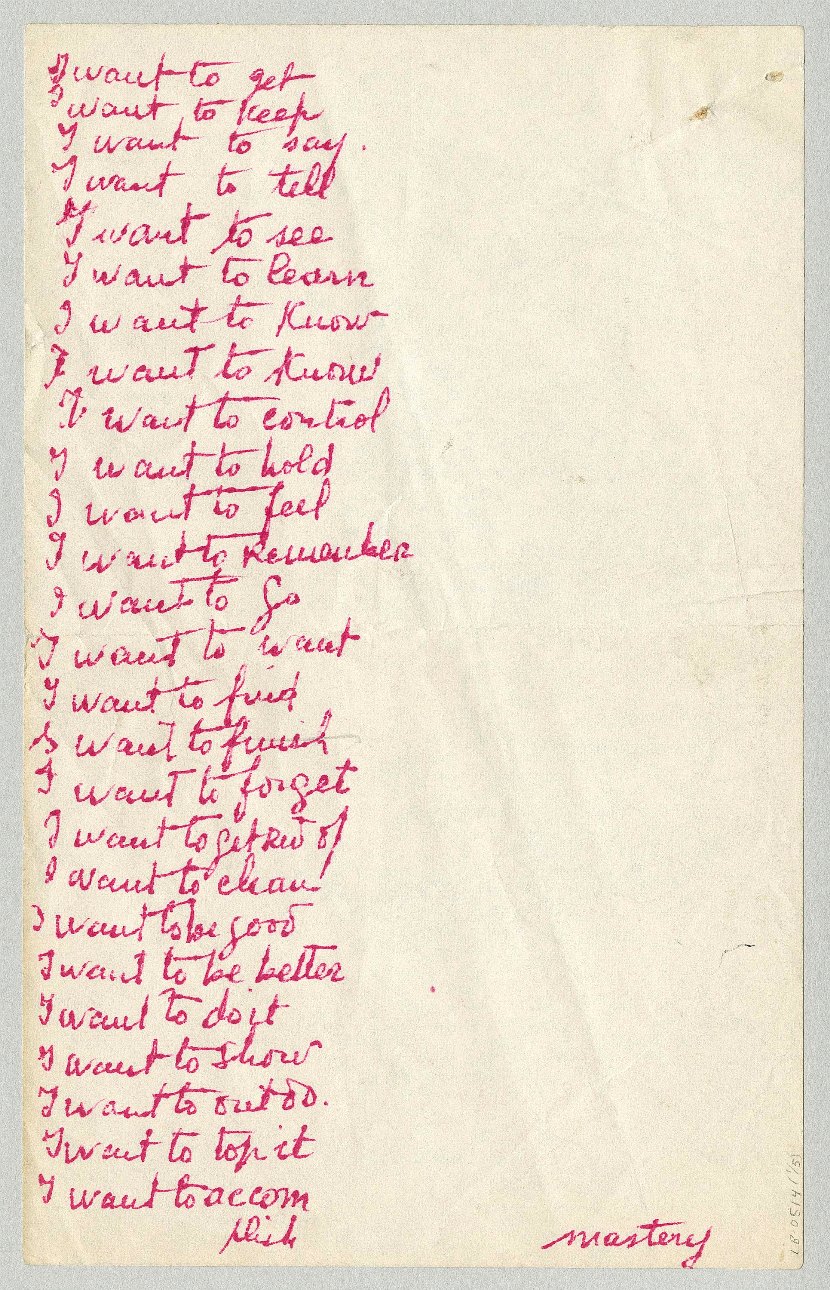

“I am sixty two years old and I have dragged myself from day to day, the result of an anxiety that only work as a sculpture has appeased”, she begins on one closely scrawled leaf. On another, perhaps a little more prosaically, she lists seven ways to “end it all”, whilst another, longer list (pictured right) a certain self-obsessive petulance makes itself apparent beneath the anguish: “I want to get/I want to keep/I want to say/I want to feel/I want to see/I want to learn”, and so it goes on, rather tediously, until we get to the final word, presented as if it might, in an ideal world that can never exist, be the sum total of demands fulfilled – “mastery”.

“I am sixty two years old and I have dragged myself from day to day, the result of an anxiety that only work as a sculpture has appeased”, she begins on one closely scrawled leaf. On another, perhaps a little more prosaically, she lists seven ways to “end it all”, whilst another, longer list (pictured right) a certain self-obsessive petulance makes itself apparent beneath the anguish: “I want to get/I want to keep/I want to say/I want to feel/I want to see/I want to learn”, and so it goes on, rather tediously, until we get to the final word, presented as if it might, in an ideal world that can never exist, be the sum total of demands fulfilled – “mastery”.

This is really stuff that any depressed or unhappy person might have written. It doesn’t particularly add to the work, and you could even argue that in some ways it diminishes it. Bourgeois’s work is always about the expression of a psychoanalytically framed anxiety, but here the source of its mystery is stripped bare. No doubt all these jottings will be of autobiographical interest to people who like to blur the lines between an artist’s work and the cult of their celebrity, but beyond the prurient interest it’s difficult to see much art historical value in it: unlike the letters of Van Gogh they give little away about the actual process of creating.

Few can doubt that at her best, Bourgeois created arresting psychodramas – impressive theatrical tableaux such the Duchampian Red Room, 1994, and, to a lesser degree, The Destruction of the Father, 1974, the first of her installations to feature stuffed fabric sculptures. It would have been rather ambitious to get any of these seminal pieces into the Freud Museum, besides which, as a domestic space and former home of Sigmund Freud, there isn't enough room. In the garden, there is, however, one of Bourgeois’s large bronze spiders from her Maman series, which, with its reproductive, egg-containing sac spied through long, articulated legs, exudes undeniable menace but also betrays the tender vulnerability of its maternal condition.

Pregnancy and motherhood feature in many of Bourgeois’s works in this exhibition, which are sparsely dotted throughout the two floors of the museum. They express the anxiety of motherhood as the usurpation of the self. In two sketchy watercolours executed in washy, seeping, blood-red paint, we witness two suckling babies angrily demanding the disembodied Kleinian breast. In a more tender but nonetheless disquieting piece, a small stuffed doll is to be found beneath a glass bell jar (main picture: A Dangerous Obsession, 2003). Her head is bowed as she cradles her bulge – a fragile glass dome in glowing red – perhaps in wonder at the life she has created, perhaps in fear and trepidation, or possibly all three. Like a specimen she is trapped, but she is also protected in this hallowed, separate space – a soft, pliable doll symbolising something of the innocent virtue of a Madonna, the sacred embodiment of motherhood.

Multiple Janus-heads and engorged sexual parts make their appearance, too. A stuffed fabric head has four grimacing faces; a figure with a tiny, pink, faceless head and outrageously large pneumatic breasts is prostrated on an instrument that resembles a bellows; a massive torso is covered in flesh-coloured stuffed berets resembling a tumourous growth of breasts; and another stuffed prostrate figure has a knife for a head, angled over the body to neatly illustrate a castration anxiety (the mutilated figure is already missing one leg, as are other figures in the exhibition).

Multiple Janus-heads and engorged sexual parts make their appearance, too. A stuffed fabric head has four grimacing faces; a figure with a tiny, pink, faceless head and outrageously large pneumatic breasts is prostrated on an instrument that resembles a bellows; a massive torso is covered in flesh-coloured stuffed berets resembling a tumourous growth of breasts; and another stuffed prostrate figure has a knife for a head, angled over the body to neatly illustrate a castration anxiety (the mutilated figure is already missing one leg, as are other figures in the exhibition).

Meanwhile, pendulous breasts are barely distinguishable from engorged penises. One of Bourgeois’s most famous pieces, the hanging bronze Janus Fleuri, 1968, has been hooked, like a hunk of butcher's meat, from the ceiling to hang just a foot or two over Freud’s famous couch. Its leg stumps and wound-like genitalia, part female, part male, appear as a gesture of mocking defiance, raging against the analytic process whilst also obediantly complying with its demands to expose the most hidden parts of the self. It's the only work which attempts a direct dialogue with its setting.

As with almost every confrontation with Bourgeois, I come away feeling the heat of a rather overcooked sensibility, with its sometimes too literal expressions of psychoanalytic symbolism. In fact, I feel as I felt when I visited the artist’s vast Tate Modern retrospective in 2008: this is an artist who has surely had too much psychoanalysis.

- Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed at the Freud Museum until 27 May

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Comments

That's a really interesting

That's a really interesting review - though I actually enjoyed the exhibition in this setting. After all, where better to display the work of "an artist who has surely had too much psychoanalysis"?!