Mona Hatoum, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Mona Hatoum, Tate Modern

Mona Hatoum, Tate Modern

The pain of life in exile provides powerful subject matter

Mona Hatoum was born in Beirut of Palestinian parents. She came to London to study at the Slade School in 1975 and got stuck here when civil war broke out in Lebanon, preventing her from returning home. In effect, she has been living in exile ever since and the sense of displacement and unease induced by being far from home permeates much of her work.

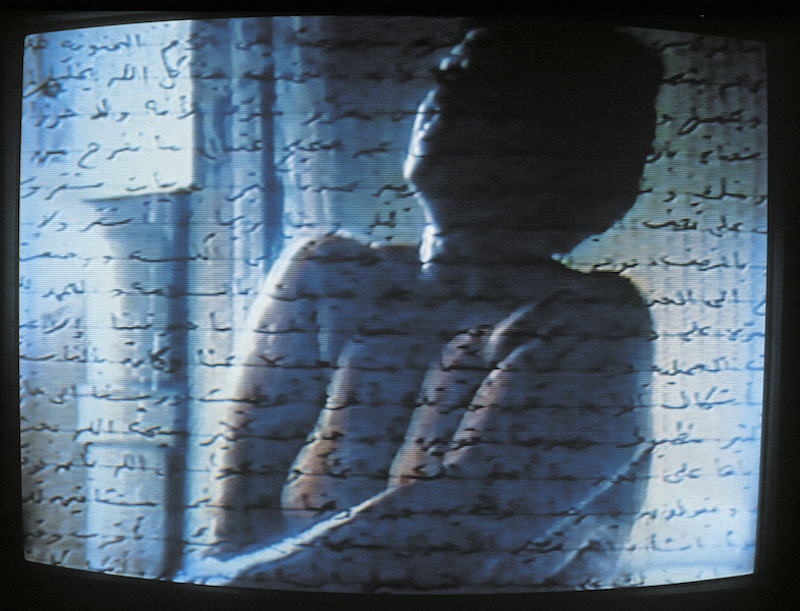

The video, Measures of Distance, 1988 (pictured below right) is a moving reflection on the love she feels for her mother, far away in war-torn Beirut. The screen is covered in a veil of arabic writing (her mother’s letters) that at first glance resembles barbed wire; trapped behind the wire, as it were, her mother is taking a shower. Meanwhile, on the soundtrack, mother and daughter hold a conversation and the artist reads extracts from her mother’s letters translated into English. The warmth permeating their voices contrasts dramatically with the emotional distance encapsulated by the image.

The notion of the familiar made distant and strange takes on sinister, even dangerous connotations in sculptures such as Daybed, 2008. A humble vegetable grater is enlarged to the size of a couch on which you would lie at your peril, and in Grater Divide, 2002, a folding cheese grater is enlarged to the size of a room divider that could take a slice out of anyone who brushed against it.

The notion of the familiar made distant and strange takes on sinister, even dangerous connotations in sculptures such as Daybed, 2008. A humble vegetable grater is enlarged to the size of a couch on which you would lie at your peril, and in Grater Divide, 2002, a folding cheese grater is enlarged to the size of a room divider that could take a slice out of anyone who brushed against it.

Homebound, 2000, comprises an entire apartment that has become a potential killing field. The items with which people surround themselves to create a sense of security and belonging – from beds, tables, chairs and cots to kitchen utensils, lamps and toys – have been wired up to deliver a lethal shock to anyone foolish enough to attempt to return home. As the electric current courses through the installation, the crackling of static fills the air and hidden lights deliver warning flashes.

Light Sentence, 1992, is less histrionic and ultimately more satisfying. An enclosure made from wire-mesh lockers is lit with a bare bulb that casts dramatic shadows as it slowly ascends and descends. Prolonged incarceration and torture are implicit in this chilling installation, which is the more powerful for not being explicit.

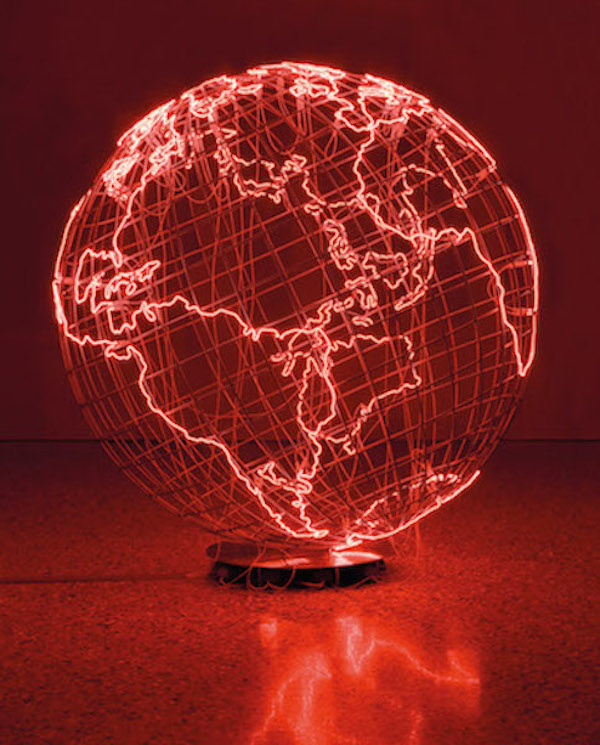

As time goes by, Hatoum’s sense of displacement does not seem to ease. On the contrary, the whole world has joined her adopted homeland in becoming a potentially explosive war zone. Hotspot III, 2009 (pictured below left), is a large globe on which the continents are outlined in red neon to indicate areas of possible future unrest.

But there’s another side to Hatoum’s work. When returning home becomes impossible, there is nothing for it but to use your own body as a resource or place of residence, as it were. Rather than being seen as waste matter to be discarded, hair and fingernails become mementoes to be cherished as an ongoing proof of life. Nails are incorporated into handmade paper or cast in blocks of resin; strands of hair are woven into fragile grids or rolled into tiny sculptures that are spread across a floor or kept prisoner in a birdcage, while a triangle of pubic hair woven into the seat of a chair adds a sexual frisson to an innocent piece of wrought ironwork. Creepy yet compelling, these traces emphasise both the fragility and durability of the body (main picture: Performance Still, 1985, 1995).

The concept of the body as a dwelling is explored literally in Corps étranger, 1994, a video which takes viewers on a journey into the artists’s body. We hear the pumping of her heart and the rasping of her breath, as an endoscopic camera travels down her throat into her oesophagus, a narrow passageway lined with slimy frills and glistening flanges. This disconcerting ride takes place beneath your feet, at the centre of a circular chamber, as though trying to suck you into the abyss of her being.

The concept of the body as a dwelling is explored literally in Corps étranger, 1994, a video which takes viewers on a journey into the artists’s body. We hear the pumping of her heart and the rasping of her breath, as an endoscopic camera travels down her throat into her oesophagus, a narrow passageway lined with slimy frills and glistening flanges. This disconcerting ride takes place beneath your feet, at the centre of a circular chamber, as though trying to suck you into the abyss of her being.

Seeing these works singly over the years, I found them extremely impressive, but gathered together in a retrospective, they seem rather too insistent. I prefer the more subtle and meditative pieces like Present Tense, 1996, a grid of blocks of olive oil soap, the colour of travertine. A map of the territories that, according to the Oslo Peace Accord of 1993, Israel must return to the Palestinians is delineated in tiny red beads pressed into the soap. Even to the casual observer, it is obvious that this plethora of small islands cannot be united into a single territory.

Turbulence (black), 2014, is a circle of black marbles that gleam malevolently as if daring you to set foot on unstable terrain, but its meaning is unclear without the companion piece Map, 1999, which is not included in the show. Map is a projection of the world delineated in colourless marbles which shift with the slightest tremour of the floor they rest on. It's a powerful metaphor for the instability threatening the fabric and peoples of planet Earth that Turbulence can only hint at.

My favourite piece is + and, 1994-2004, a simple yet poetic sculpture that embodies the stubborn optimism which, against the odds, fuels human endeavour. A metal arm rotates over a circular bed of sand; one half of the arm is serrated, the other smooth. The circles combed in the sand by the serrated arm are instantly erased by the smooth arm. No traces remain, the slate is endlessly wiped clean, yet the arm continues to revolve; it's the effort that counts, rather than the outcome. Minimalism with added meaning – this is my idea of the perfect work of art.

- Mona Hatoum at Tate Modern until 21 August

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Add comment