From Paris: A Taste for Impressionism, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

From Paris: A Taste for Impressionism, Royal Academy

From Paris: A Taste for Impressionism, Royal Academy

A potpourri of paintings showing sun-dappled scenes from France

As the clouds continue and the rain pours down, the Sackler Gallery at the Royal Academy is filled with sun-dappled scenes from France. The anthology is a potpourri of paintings culled from the remarkable collections put together by the millionaire race horse breeder and art obsessed Sterling Clark – the fortune inherited from his grandfather’s involvement with the Singer Sewing Machine company - and his French actress wife Francine.

The Clarks eventually had nearly 40 works by Renoir, and by the 1930s Clark was identifying the artist as perhaps the greatest, or among the top dozen, in all of western art history, and as a colourist never equalled. The quality of the Renoirs on view at the RA is high, and subjects sometimes unexpected: several are a welcome gloss on the usual plump pretties he is now best known for.

There is an early, perhaps unfinished, self portrait, 1874, showing a sharp nosed young man, almost sniffing out the art world, with an ambiguous gaze, bird-eyed curious, searching, uncertain.

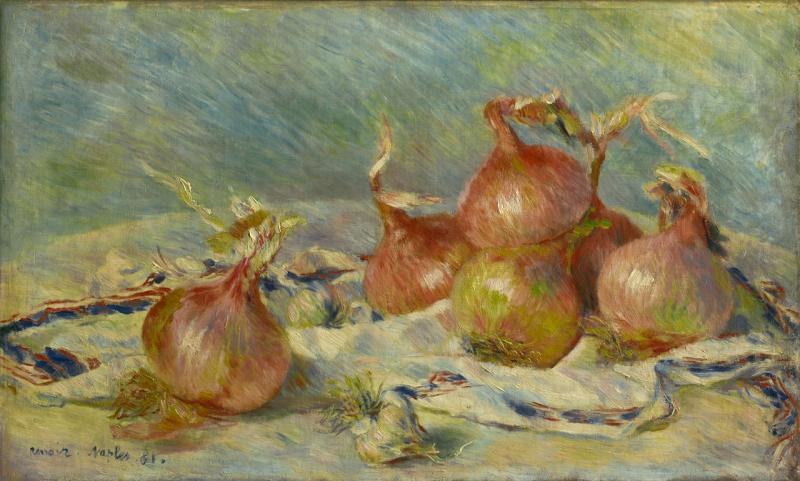

An oil sketch titled Sunset, 1879-81, which cannot be pinned down geographically, is almost totally abstract, its incandescent blues, pinks and primrose yellows sweeping across the canvas. Only the swathe of slightly deeper blues horizontally brushed across the scene gives a subtle hint of twilight, indicating the horizon. A tiny silhouette of a sailing boat tells us that the glinting pinkish orange paint is the sun reflected on the wave ruffled sea. Onions, 1881 (main picture), yes, just six plain onions (and some garlic too) is a surprisingly sensuous still life of those cooking staples, bursting with colourful rotundity, their papery skins forming plumed banners: making from the ordinary something oddly dignified and appealingly lively. Onions with attitude. The whole is both exuberant and controlled, authoritatively improvised.

An oil sketch titled Sunset, 1879-81, which cannot be pinned down geographically, is almost totally abstract, its incandescent blues, pinks and primrose yellows sweeping across the canvas. Only the swathe of slightly deeper blues horizontally brushed across the scene gives a subtle hint of twilight, indicating the horizon. A tiny silhouette of a sailing boat tells us that the glinting pinkish orange paint is the sun reflected on the wave ruffled sea. Onions, 1881 (main picture), yes, just six plain onions (and some garlic too) is a surprisingly sensuous still life of those cooking staples, bursting with colourful rotundity, their papery skins forming plumed banners: making from the ordinary something oddly dignified and appealingly lively. Onions with attitude. The whole is both exuberant and controlled, authoritatively improvised.

The asymmetrical Apples in a Dish, 1883, is equally unexpected, greens and reds playing off each other, the apples’ blemished pockmarked surfaces shiny and mat both, the globular fruits irregular in shape, their imperfections marking the individuality of each fruit.

There is an 1850s self portrait of the young Degas (pictured above right) who often took himself as a subject, his searching look full of thoughtful enquiry, a hint of the massive intellectual and visual engagement to come. His small, imaginatively choreographed group of horses and their jockeys, Before the Race, 1882, the horses walking and stretching out in a friendly group, the sun glinting off their shining, burnished chestnut coats, demonstrates his absolutely formal control of the apparently informal group poised in a captured moment.

Spaciously and thematically set out in the exquisitely proportioned rooms of the Sackler Galleries, the visitor can occasionally discern the unusual and the slightly darker. There is an early Monet of a storm at sea, with vividly strong buildup of paint applied by the palette knife, a streak of pale incandescent green heralding the calm before the frenzy. High factory chimneys belching out picturesque plumes of smoke delicately dominate the horizon of an apparently tranquil river scene by Camille Pissarro, The River Oise, Pointoise, 1873 (pictured left). Its extraordinary cluster of factory chimneys – an alcohol distillery - reach up into the cloudscape, reflected too in the water below.

Spaciously and thematically set out in the exquisitely proportioned rooms of the Sackler Galleries, the visitor can occasionally discern the unusual and the slightly darker. There is an early Monet of a storm at sea, with vividly strong buildup of paint applied by the palette knife, a streak of pale incandescent green heralding the calm before the frenzy. High factory chimneys belching out picturesque plumes of smoke delicately dominate the horizon of an apparently tranquil river scene by Camille Pissarro, The River Oise, Pointoise, 1873 (pictured left). Its extraordinary cluster of factory chimneys – an alcohol distillery - reach up into the cloudscape, reflected too in the water below.

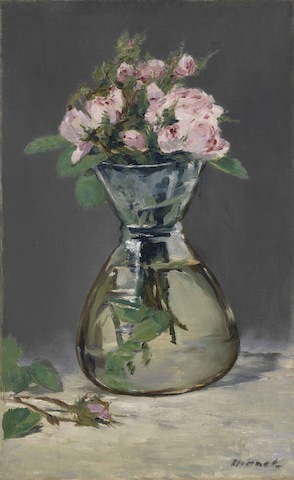

Clark also enjoyed pompier French art, and the parallel influences of the establishment and the academy. Carolus Duran, John Singer Sargent’s teacher and the most fashionably successful portrait painter of his day is represented by a sensitive and compelling portrait of The Artist’s Gardener which is surprisingly evocative of Manet, echoing Velázquez, as Manet did. Manet himself among several paintings is superbly shown in his modest Moss Roses in a Vase, 1882 (pictured right) painted in his last year. The wilting bouquet shedding its leaves, is held in a waterfilled glass vase, gleaming with light. The subtly overwhelming pleasure of Manet’s play with texture, colour, composition, makes it a painting pulsating with vitality.

Clark also enjoyed pompier French art, and the parallel influences of the establishment and the academy. Carolus Duran, John Singer Sargent’s teacher and the most fashionably successful portrait painter of his day is represented by a sensitive and compelling portrait of The Artist’s Gardener which is surprisingly evocative of Manet, echoing Velázquez, as Manet did. Manet himself among several paintings is superbly shown in his modest Moss Roses in a Vase, 1882 (pictured right) painted in his last year. The wilting bouquet shedding its leaves, is held in a waterfilled glass vase, gleaming with light. The subtly overwhelming pleasure of Manet’s play with texture, colour, composition, makes it a painting pulsating with vitality.

It is a shock to come upon the rather ludicrous orientalism of, for example, Gerome’s Slave Market, and his Snake Charmer. These technically accomplished but ridiculous compositions, top of the pops of their day, point up the technical innovations and freshly imaginative vision and intellect of the impressionists. Far from being déjà vu, it turns out that they still have more to show us.

- From Paris: A Taste for Impressionism at Royal Academy until 23 September

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Add comment