Every time you turn a corner, he’s there, on yet another monitor. Either the exhibition curators have a sense of humour, or Alastair Campbell really is the last word on propaganda, a subject about which the British Library has mounted an excellent and occasionally provocative exhibition.

On one screen Blair’s former spin doctor can be seen talking with some regret. The P-word, he is saying, is so sullied that it’s now no more than a byword for lying. Personally, I feel more comfortable with the Jeremy Paxman line: “Why is this lying bastard lying to me?” Perhaps Campbell could mount a campaign to give propaganda the respect he feels it's due.

You get to an exhibition design banner showing Churchill’s face merged with Hitler’s and your jaw drops slightly

Propaganda isn’t a modern phenomenon, but given the reach of 20th-century communications where the weapon is persuasion over coercion, it has a special place in 20th-century politics – and with it a legion of modern political theorists to dissect it. This exhibition is largely concerned with the 20th century, and one enters it by walking over a projected floor image of writhing, propagating viruses, a perfect visual metaphor for our times where “going viral” is the wish of every marketing campaigner.

We are then confronted by an army of faceless mannequins on which we find quotes from politicians, tyrants and philosophers. “It may be a good thing to possess power that rests on arms. But it is better and more lasting to win the heart of a people,” reads one. Another reads, “The art of propaganda is not telling lies but rather seeking the truth you require and giving it mixed up with some truths the audience wants to hear.”

Those quotes are, respectively, from Joseph Goebbels, the Third Reich’s minister for propaganda, and Richard Crossman, Labour minister under Wilson. Could you tell who was the democrat? A public declaration of a love of arms by which one might control a population might have given a clue, but essentially they say the same thing.

Another states that “Everything is propaganda” which is rather typical of the broad, sweeping generalisations of a French political theorist (Jacques Driencort). Though you might counter that there’s more than an element of truth in this, a genuine belief that everything is, indeed, propaganda, does have a tendency to kill all intelligent debate as to its nature. And what part do empirical evidence and truth play in the art of persuasion, exactly?

The exhibition has taken a broad-brush approach, rather emulating the quote from Driencort above. Though, of course, I’m sure it’s hardly aiming for any kind of moral equivalence between the propaganda of Nazi Germany (you’ll find plenty of horrifying anti-Semitic films to turn your stomach) and growing your own veg in Britain’s World War Two campaign “Digging for Victory”, one does jump from one to the other in earnest. This is hardly surprising for an exhibition teeming with material, from Soviet propaganda posters to well-known safety campaigns closer to home (you may recall one of the most successful of these was "Clunk Click Every Trip", with Jimmy Savile, but that seems to have been expunged from history, a bit like the erasing from photographs of inconvenient figures in more restrictive regimes), but then you get to an exhibition design banner showing Churchill’s face merged with Hitler’s and your jaw drops slightly: the right side belongs to Churchill, the left to Hitler. Heavens, what were the curators thinking?

Soviet Russia under Lenin had a legion of brilliant artists and designers such as El Lissitzky to help to fight the home propaganda wars, but ask the same of an English artist and you’re never quite sure what you’ll get. Paul Nash was a war artist in both the first and the second world wars, but he was clearly no propaganda artist. His depiction of Hitler as some weird airborne shark flying above a mass of clouds and German fighter planes was turned down by the Ministry of Information who couldn’t quite work out what it was trying to say. Its message was perhaps not quite as clear-cut and forthright as was hoped.

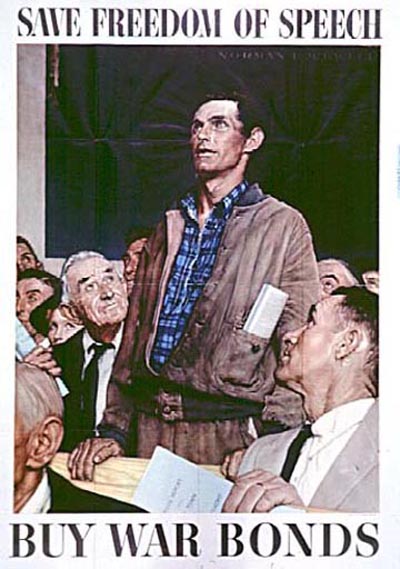

Over in America, however, Norman Rockwell’s homely Apple Pie patriotism had little difficulty in expressing itself along lines that everybody could readily understand. His Four Freedoms paintings, inspired by a speech given by Roosevelt, were used to promote war bonds when they were exhibited across America and helped raise much-needed funds for the war effort (pictured right: Norman Rockwell, Save Freedom of Speech).

Over in America, however, Norman Rockwell’s homely Apple Pie patriotism had little difficulty in expressing itself along lines that everybody could readily understand. His Four Freedoms paintings, inspired by a speech given by Roosevelt, were used to promote war bonds when they were exhibited across America and helped raise much-needed funds for the war effort (pictured right: Norman Rockwell, Save Freedom of Speech).

At the end of this exhibition we encounter an LED board with flashing anonymous Twitter messages highlighted variously in yellow (for positive comments), blue (negative) and white (neutral), to indicate responses to recent big news events, such as last year’s feel-good Olympic opening ceremony, orchestrated by Danny Boyle. It feels like the contemporary equivalent of Mass Observation, except now we’re all watching each other. Social media has given us the means to respond immediately to events, and perhaps influence them as never before. Quite to what extent it can do this remains the unresolved question of this thoroughly thought-provoking exhibition.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment