The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters, Royal Academy

The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters, Royal Academy

His own words show the fine, delicate, heartless truth of the man

This exhibition may claim to reveal the real Van Gogh through his letters, but what of the Sunflowers, the Self-Portrait With Bandaged Ear, oh, and Starry Night, with its roiling night sky and dark, mysterious cypress tree? What even of the dizzying Night Café, with its migraine-inducing electric lamps, its violent clash of reds and greens and the walls that threaten to collapse inwards, as if the painter had been hitting the absinthe all night?

We may know them intimately, for they exist in the collective imagination as surely as they exist on solid canvas. But we never get tired of seeing them – even, it seems, if we have to stand in a snaking queue in the driving rain for the tickets. How could we? They are magnificent, after all. So will the fact that they don’t make an appearance in this show prove a disappointment for the legions who claim they are fans? And that, in their place we will find the less familiar - paintings that won’t all necessarily possess that instantly arresting wow factor? Undeniably for some, and very possibly for others, yes.

But to all those who want the UK comeback gig to include all the popular favourites – and why wouldn’t you? – we’ll have to get one thing straight from the start: this is an exhibition that seeks to do something other than provide a calling card of works for an artist whom many will know only through those blockbuster images (and, of course, through the fact that he lopped off his earlobe – yes, just the lobe, not the whole thing). It doesn’t just want to razzle-dazzle us, you see.

Instead it wants to quietly seduce, while doing something altogether more difficult, more serious: quite simply, it wants us to get acquainted with the artist behind the myth, with the man behind the hackneyed image. After all, how many of us might really be thinking of Kirk Douglas in the thrilling, Technicolor Hollywood biopic Lust for Life – all that fiery passion and muscular, jaw-clenching intensity – rather than the intensely lonely, really rather socially inept, sometimes boorish and often incredibly exasperating man of many letters that close study of his correspondence reveals?

So how far does this exhibition succeed in taking us beyond the myth? For all those with a well-thumbed copy of the Penguin edition of the letters – and who have thumbed through it themselves – you will know quite a lot about Vincent already. Apart from knowing that this incredibly prolific artist only painted for ten years of his life before his suicide aged 37, you will also know that he was incredibly close to Theo, his younger brother by four years, on whose financial and emotional support he relied for most of his adult life.

You’ll know that most of his letters were addressed to him, and that it wasn’t always an easy relationship (in Theo’s words, Vincent was a man who appeared to have “two different beings in him, the one marvellously gifted, fine and delicate, the other selfish and heartless”.) You'll know that he was not only a prodigious writer but a voracious reader, too, reading Dickens and Shakespeare in the original, and all of the 20 novels in Zola’s Rougon-Macquart cycle. (For Vincent, the French naturalist writers “paint life as we feel it ourselves, and thus satisfy that need which we have, that people tell the truth”. Like them, he wanted to paint only the here and now of ordinary contemporary life.) You’d know, too, that he’d often restart a letter, when he had already signed off several times, because his feverish mind would always think of new things to add – and because he had so few people to talk to in person – and that these restless letters would often go on for many, many pages.

Each letter refers directly to the paintings and the graphic works on display

You’ll know all this, and, if you care to go to the expense of buying the recently published re-translations of the letters in a six-volume edition from Thames and Hudson, with its many scholarly annotations, footnotes, cross references and reinstatement of all previous expurgations, you’ll get to know even more (it’s nearly £400, although you can view the online version for free). This exhibition comes on the back of this new translation.

So how close, again, do we really get to the real Van Gogh here? With 65 paintings – among them, still some exceptionally arresting works – 30 drawings and etchings, and some 40 letters and letter-sketches (fragile and rarely seen, these will soon be returned to their vaults), we do, indeed, gain an insight into the mind of this troubled artist. Each letter refers directly to the paintings and the graphic works on display, hence why there are no works included that aren’t referred to in the correspondence, either as sketches or lengthy descriptions.

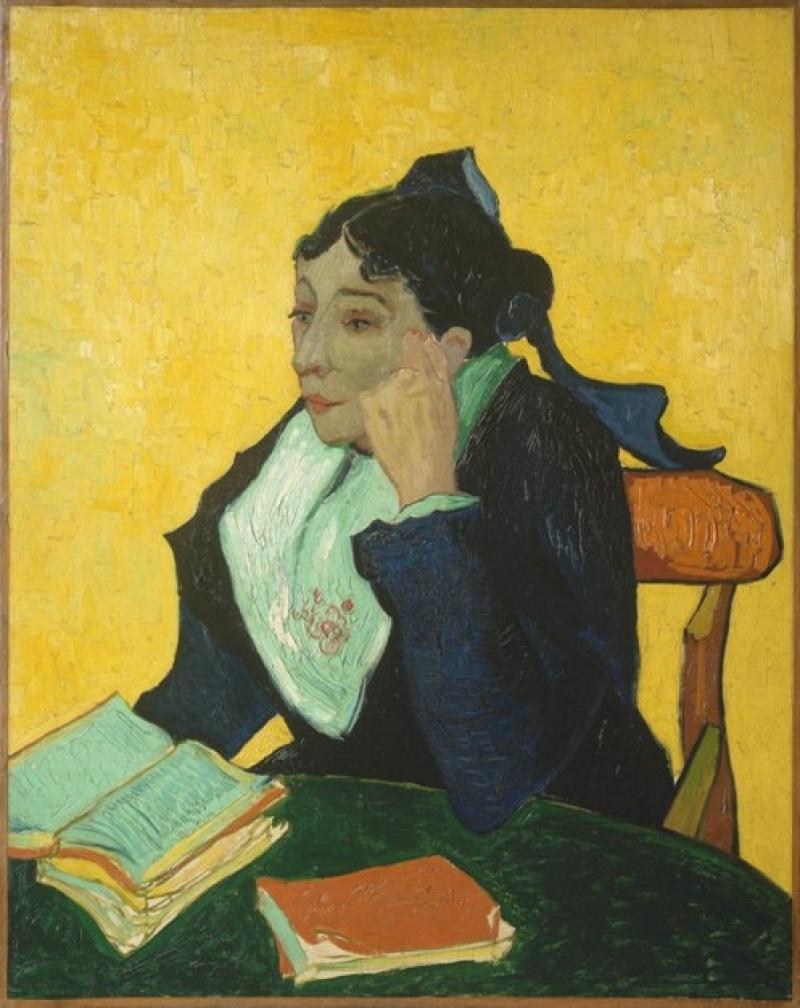

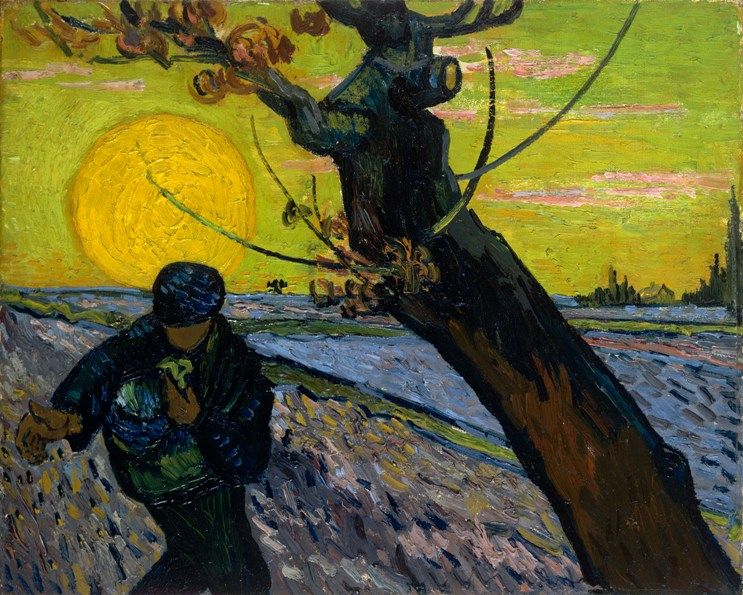

This means that the insights are largely confined to Van Gogh working out many of his artistic ideas and providing Theo with a working description of the latest painting. “Here’s a croquis [sketch] of the latest canvas I’m working on, another sower. Immense lemon yellow disc for the sun. Green-yellow sky with pink clouds. The field is violent, the sower and the tree Prussian Blue.” That is a description of his marvellous Japanese woodblock-inspired The Sower, of 1888. Or, in describing one of his monumental Cypresses whose swirling forms suggest the strong mistral winds of southern France, he writes: “The cypress is beautiful as regards lines and proportions, like an Egyptian obelisk.” Astonishingly, we also learn that one great painting L’Arlesienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux with her Books, 1888, “was knocked off in one hour”.

On a more personal note, you’ll find moving lines such as these: “What else can one do, thinking of all the things whose reason one doesn’t understand, but gaze upon the wheatfields. Their story is ours, for we live on bread.” Or, here, when he is writing to Theo from the mental asylum at Saint Rémy in the last year of his life: “In seeing the reality of the life of the diverse mad or cracked people in this menagerie, I’m losing the vague dread, the fear of the thing. And little by little I can come to consider madness as being an illness like any other.”

It is a ruptured mind, for sure, but one, as we see time and again, that retained a beautiful, articulate lucidity for much of its possessor’s life. In such a relatively understated, but still thoroughly absorbing exhibition, perhaps we may appreciate the eloquence of Van Gogh’s voice even more.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Comments

...