Rembrandt: The Late Works, National Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Rembrandt: The Late Works, National Gallery

Rembrandt: The Late Works, National Gallery

In his last decade, the Dutch artist suffered hardship, but painted some of his most enduring masterpieces

All human life, as they say, is here: we witness displays of warmth and tenderness in virtuous matrimony; reflection and contemplation in quiet solitude. We respond to the soft seductions of the flesh in its yielding ripeness, and we feel the pathos of the withering of the flesh in age; there’s even the mocking of the aged flesh still lusting for the piece of the old action. There’s civic pride and intellectual curiosity.

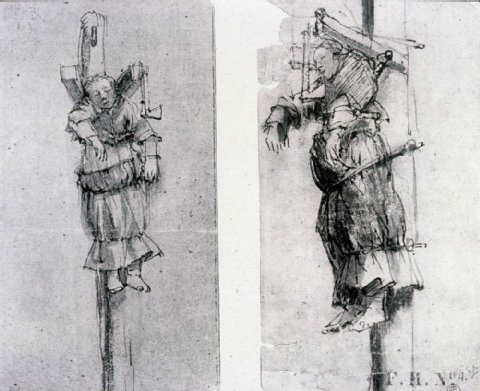

But while there is drama, there is an absence of spectacle. Rembrandt doesn’t do spectacle. It is not the Dutch, Protestant way, and it’s not Rembrandt’s way. Rembrandt’s way is to express the concentrated intensity of human experience, while addressing its quotidian nature. The one doesn’t cancel out the other, but the ordinary is heightened and made somehow mysterious – as all great art is somehow mysterious. We see a young woman, identified as 18-year-old Elsje Christiaens, hanged from a gibbet. An axe dangles from the gibbet by her head – it looks small and unthreatening here – so that those gathered for her public execution may grasp the nature and method of her crime. She used it to murder her landlady.

Rembrandt sketched the young woman from life, as it were, and here she appears in two small, broadly sketched but finely shaded ink drawings, one frontal, the other in three-quarter profile (pictured below). Her head rests on one awkwardly raised and twisted arm. The noose we do not see, for her head is pushing down into her body – she’s bunched up. But her face appears in perfect repose.

As if in even deeper slumber we find another who, no doubt, had also been sentenced to the gallows – this time on an anatomy table, his brains exposed and with the parted flesh of his skull – such an excess of flesh – framing his features like lustrous hair. The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Joan Deyman (main picture), painted eight years before Elsje Christiaens, in 1656, is Rembrandt’s second celebrated anatomy painting, the first being The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp in 1632, the painting with which Rembrandt made his name, making him, at the age of 26, the most famous and sought after painter in Amsterdam – although that good fortune wasn’t to last. This second painting is merely the surviving fragment of a fire in 1723, and the canvas was subsequently recut, though a sketch does survive outlining the original composition – the cadaver still at its centre, surrounded by men of the surgeons’ guild and gentleman lookers-on.

As if in even deeper slumber we find another who, no doubt, had also been sentenced to the gallows – this time on an anatomy table, his brains exposed and with the parted flesh of his skull – such an excess of flesh – framing his features like lustrous hair. The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Joan Deyman (main picture), painted eight years before Elsje Christiaens, in 1656, is Rembrandt’s second celebrated anatomy painting, the first being The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp in 1632, the painting with which Rembrandt made his name, making him, at the age of 26, the most famous and sought after painter in Amsterdam – although that good fortune wasn’t to last. This second painting is merely the surviving fragment of a fire in 1723, and the canvas was subsequently recut, though a sketch does survive outlining the original composition – the cadaver still at its centre, surrounded by men of the surgeons’ guild and gentleman lookers-on.

The dead man’s body has been dramatically foreshortened, and the perhaps somewhat shocking allusion to Mantegna's Lamentation of Christ would not have been lost on the many who first saw it. Does this suggestive reference lend the dead man dignity and touch us with the added weight of pathos? The dignity is all too evident in the dead man’s humanity, held up like a mirror to our own; we look straight into his face, after all. The painting makes for a very visceral kind of memento mori, that genre of painting that Dutch artists of the 17th century seemed particularly to specialise in and excel at. But instead of a grinning skull we merely get the cap of a skull, held by the surgeon’s assistant like a kidney tray, or perhaps a kind of votive offering.

Separated by 24 years, the differences in technique between Rembrandt’s two surgeons’ guild paintings is evident in the looser, broader handling of paint in the later work. This is an exhibition that looks at Rembrandt’s late period – a period covering, generously, some 15 years of the artist’s life up to his death, aged 63, in 1669, so only the compelling later anatomy painting is on display, along with 40 works on canvas, 20 drawings and 30 prints, including a tiny, delicate and exquisite self-portrait that opens this show.

Here, in this spare and beautifully designed exhibition – look, no wall texts (it's all printed in a pamphlet) – we find an artist tirelessly experimenting, in both painting and printing techniques. He was the first artist to use a palette knife to work paint onto canvas instead of just mixing colours with it. With this he built up thick, oily swathes and peaks of paint, to give an almost sculptural texture to detailed surfaces, such as the fleshy contours of a face, while leaving other areas of the canvas barely touched beyond the underpaint and a few quick delineating strokes – hands were often a case in point.

The difficulties of Rembrandt’s later years have been well documented: the bankruptcy, from which he would never recover; the falling out of artistic favour; the death of his mistress Hendrickje Stoffels, initially employed as his infant son’s nursemaid and carer (his wife Saskia had died in 1642, and some 20 years later he even sold her grave to try to pay off his creditors); and, in the most devastating blow of all, the death of his only son Titus, two years before his own.

And yet these years saw the completion of some of Rembrandt’s most powerful works: those intense late self-portraits, five of which begin the exhibition; Bathsheba with King David’s Letter, c.1654, oozing with subtle eroticism; the heart-rendingly tender Portrait of a Couple as Isaac and Rebecca, c.1665, better known as The Jewish Bride, of which Van Gogh, somewhat melodramatically, was to say, “I would gladly give up 10 years of my life to sit in front of the painting for a fortnight, with only a dry crust of bread to eat”; and the monumental history painting The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis, c.1661 (pictured above), which depicts the one-eyed and rather monstrous-looking Batavian leader exhorting his warriors to swear an oath against the Romans.

And yet these years saw the completion of some of Rembrandt’s most powerful works: those intense late self-portraits, five of which begin the exhibition; Bathsheba with King David’s Letter, c.1654, oozing with subtle eroticism; the heart-rendingly tender Portrait of a Couple as Isaac and Rebecca, c.1665, better known as The Jewish Bride, of which Van Gogh, somewhat melodramatically, was to say, “I would gladly give up 10 years of my life to sit in front of the painting for a fortnight, with only a dry crust of bread to eat”; and the monumental history painting The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis, c.1661 (pictured above), which depicts the one-eyed and rather monstrous-looking Batavian leader exhorting his warriors to swear an oath against the Romans.

This last work was commissioned for Amsterdam’s new town hall but was ultimately rejected, then later cropped, probably by Rembrandt himself, though it is still a very big painting. Suffused with fiery reds and molten oranges, its feverish, almost radioactive tones are reminicent of one of Degas’ own late paintings. It is a very strange and rather unsettling masterpiece. Far too rough and wild, one imagines, for those good burghers of Amsterdam.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Add comment