Thomas Schütte: Faces and Figures, Serpentine Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Thomas Schütte: Faces and Figures, Serpentine Gallery

Thomas Schütte: Faces and Figures, Serpentine Gallery

A powerful and disarming show by the German artist

On the evidence of this Serpentine exhibition of huge sculptures, small sculptures, photographs, drawings, watercolours and prints, the German artist Thomas Schütte is obsessed, but obsessed, with faces. It is billed as the first show to focus entirely on his portraiture, of himself, his friends, and from the imagination. And the focus helps the visitor to grasp how playfully serious – or seriously playful – the artist is.

He shows us he can do any idiom in various media. He can distort representation making faces almost unbearably malleable. Are these people menacing, sneering, contemptuous, frightened, or fearful? And then here are lots of relatively straightforward drawings, almost touchingly the kind any good amateur could put forward, seemingly inhabitants of an unthreatening middle-class milieu.

This concise anthology acts as a subtext to his immensely productive outpourings, gently satirical as in his architectural Ikea houses, his temples and meditations on museums, and his installations of ceramic urns entitled Is there Life Before Death? So there Damien Hirst: Schütte’s elusive poetic titles are succinct and thought-provoking, with one series of semi-imaginary portrait heads is simply called Dirty Dictators. This spacious show is not only resonant in its own right, but acts as a helpful introduction to a highly educated imagination that never strays from the human, from the artifacts people surround themselves with to the human beast itself.

This concise anthology acts as a subtext to his immensely productive outpourings, gently satirical as in his architectural Ikea houses, his temples and meditations on museums, and his installations of ceramic urns entitled Is there Life Before Death? So there Damien Hirst: Schütte’s elusive poetic titles are succinct and thought-provoking, with one series of semi-imaginary portrait heads is simply called Dirty Dictators. This spacious show is not only resonant in its own right, but acts as a helpful introduction to a highly educated imagination that never strays from the human, from the artifacts people surround themselves with to the human beast itself.

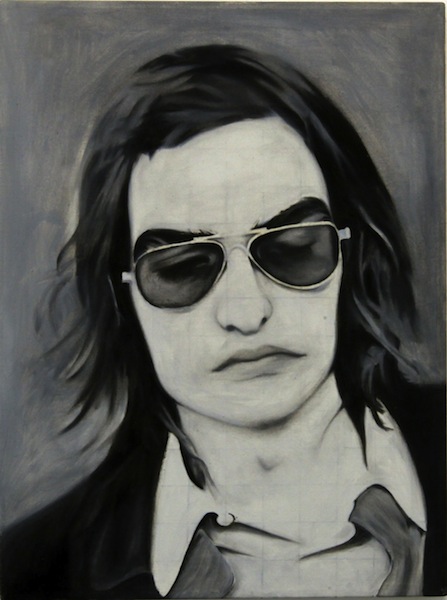

Outside the gallery there are two huge patinated bronze sculptures, each like adult Siamese twins, the bodies swaddled, with no apparent limbs, supported by a tripod. From these over life-size statues two rather caricatured heads emerge at oblique angles to each other. United Enemies is the explanatory titles. So we are a little discombobulated before rather disarmingly inside the Serpentine we start with an early self portrait, of 1975 (pictured above right; © 2012 Gautier Deblonde) the artist as a rather romantic creature, dishevelled hair, open-neck shirt, dark glasses, perhaps in recovery mode from the night before: art student idiom.

Schütte spent some seven years at the Dusseldorf art academy, the seeding ground for the dominant avant garde of Europe, and where he was taught by Gerhard Richter, amongst other eminent artists. He still lives in Dusseldorf, which, in the 1970s, was actually described in a municipal directory as the City of Artists.

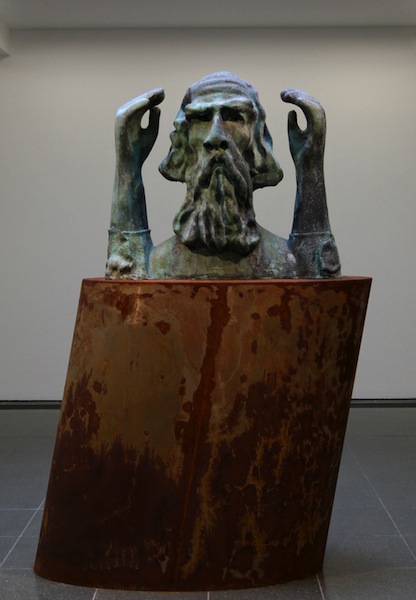

Gently mocking yet curiously powerful, the self-portrait faces 2011 Memorial for unknown artist (pictured left; © 2012 Gautier Deblonde) in which a bearded guru, arms upraised in salute or supplication, emerges from a coppery coloured steel cylinder. The 2010 steel sculpture, Father State, is perhaps even more explicit, a dignified berobed and becapped leader, but of course we do not know whether he is a hero or a dictator, or a hero-turned-dictator. The piece could be a cliché or a parody or a straightforward piece of subtle admiration of someone who is genuinely virtuous – or who has got away with it.

Gently mocking yet curiously powerful, the self-portrait faces 2011 Memorial for unknown artist (pictured left; © 2012 Gautier Deblonde) in which a bearded guru, arms upraised in salute or supplication, emerges from a coppery coloured steel cylinder. The 2010 steel sculpture, Father State, is perhaps even more explicit, a dignified berobed and becapped leader, but of course we do not know whether he is a hero or a dictator, or a hero-turned-dictator. The piece could be a cliché or a parody or a straightforward piece of subtle admiration of someone who is genuinely virtuous – or who has got away with it.

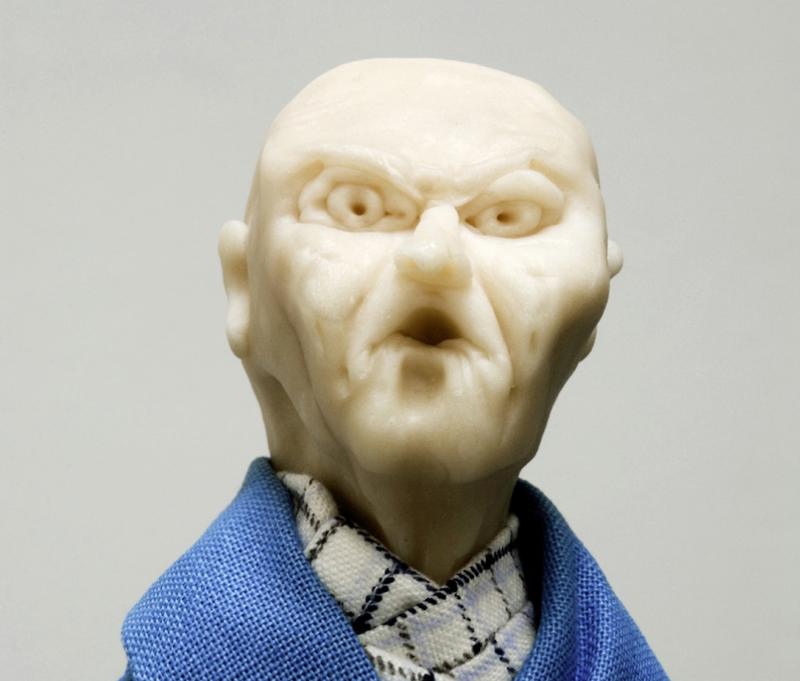

A room full of patinated bronze heads on steel shelves mocks those neoclassical interiors where contemporary worthies, or sages from the past, divine or otherwise, are ranged in procession to look down on the mortals below. Entitled Jerks, they appear like parodied figures of authority. Innocenti is a series of photographs of whitish heads, their features pushed every which way, but their hollowed-out eyes the conventional outlines of classical sculpture. The most elaborate faces look as though they are made of silly putty, or melting wax, their facial features either on the point of dissolution or of hardening (Medardo Rosso, the underated Italian symbolist comes to mind). Sometimes they remind the spectator of faces which have suffered horrific burns or assaults of other kinds.

The mood is always ambivalent, ambiguous, changeable and unpredictable. Instability is always implicit. We are disarmed because we recognise what is being shown, yet also made uneasy, startled and surprised. We leave wondering what kind of face we ourselves inhabit, all too aware of the enigma of appearance and its metamorphoses – and the inescapable imminence of decay.

- Thomas Schütte: Faces and Figures at the Serpentine Gallery until 18 November

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Add comment