Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision, National Portrait Gallery

Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision, National Portrait Gallery

The Bloomsbury writer's brilliance distilled in a powerful and deeply moving exhibition

Do we need more? Over the past 60 years thousands of books and bibliographies about Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) and the group of friends, lovers, spouses, partners, children, and houses with which she is associated, have been published, not to mention movies and plays and a more hidden mountain of academic dissertations.

There have been books about the books, and thousands upon thousands of photographs of the various permutations of their social life have been archived and many published. There have been major exhibitions in the past 20 years, a continual drip-feed of small specialist shows, and permanent collections both private and public, from paintings to ephemera, in museums, libraries and universities in England and the United States, and, of course, Virginia Woolf Societies. Bloomsbury inspires obsession.

But this succinct and emotionally direct anthology at the National Portrait Gallery does something more, and is a marvellous introduction to a staggeringly complex character enmeshed in a network of those who were profoundly engaged in private creativity, scientific investigation and public engagement.

Messed-up yet almost hilariously productive lives were a speciality of the group

Appearances may be deceiving, but they also show something, and here is a trajectory of appearance, expressed both in the visual arts and also – and they too as physical objects are revealing – books, pamphlets and letters. They are all here, all that coterie, that clique and circle of friends and lovers who informed British cultural and political life for half a century, and whose legacy is massively significant today. As a wit once observed, this was a group that lived in squares (Bloomsbury itself), loved in triangles and talked in circles.

But here there is a sharp focus, a visual biography of one of the two sisters at its heart: Virginia Woolf, writer, novelist, biographer, critic, pamphleteer, essayist, publisher, friend, sister, aunt and wife. It was the beautiful, ethereal, emotionally fragile and intermittently severely mentally ill Virginia – several breakdowns, and finally suicide – who said, “Words are an impure medium, better far to have been born into the silent kingdom of paint”. She admired her painter sister Vanessa Bell unreservedly, and, too, the ebullient, profoundly brilliant and irresistibly influential critic-historian and painter Roger Fry, whose biography she wrote. Yet she also said that words survive the changes of time almost better than any other substance.

About 150 objects are on view – portraits by varied hands, including Duncan Grant and Bell – that form a surprisingly satisfying and illuminating, even profound, examination of a life, and to a certain extent not only its personal influence but its consequences.

The compilation charts her course from the famous photographs of Virginia’s ethereal beauty when she was just 20 (pictured right: Virginia Stephen by George Charles Beresford, July 1902) to the simple wooden walking stick Virginia left on the riverbank by the river Ouse when she walked into the water, her coat pockets filled with stones, to drown herself at the age of 59. For the first time the letters she left, both dispassionately and distressingly beside herself as she wrote to her older sister Vanessa and her husband Leonard at the prospect of yet another oncoming breakdown, are on display. The handwriting is clear, her self analysis perhaps unanswerable.

The compilation charts her course from the famous photographs of Virginia’s ethereal beauty when she was just 20 (pictured right: Virginia Stephen by George Charles Beresford, July 1902) to the simple wooden walking stick Virginia left on the riverbank by the river Ouse when she walked into the water, her coat pockets filled with stones, to drown herself at the age of 59. For the first time the letters she left, both dispassionately and distressingly beside herself as she wrote to her older sister Vanessa and her husband Leonard at the prospect of yet another oncoming breakdown, are on display. The handwriting is clear, her self analysis perhaps unanswerable.

Though the focus is sharply on Virginia, it is accompanied by the two people closest to her: Vanessa, whose dustjackets and illustrative woodcuts were inseparable from almost all of Virginia’s books and pamphlets, and Leonard, described by Virginia herself – a radical revolutionary and original as she was, she was nevertheless, by birth and upbringing, a fully paid-up member of the English upper-middle class – as “the penniless Jew”. With their support through horrible breakdown after breakdown, Virginia sustained a prodigious output of reviews, essays, fiction and non-fiction, of a uniquely individual and persuasive brilliance.

It was no accident that the Woolfs called on Freud in his Hampstead house, that her brother Adrian (and his wife) became psychoanalysts, and we see a photograph of Freud in his Hampstead study. Here too is Duncan Grant’s cousin, and Lytton Strachey’s brother, James, portrayed in Grant’s portrait in precise yet casual mode, long legs stretched out as he almost slumps in his chair, his hand resting on a pile of books. James Strachey was to be the first and most influential translator of Freud into English, all 23 volumes of it. Messed-up yet almost hilariously productive lives were a speciality of the group: here are photographs of TS Eliot in a buttoned-up suit, next to Virginia; in one his infamously mad wife Vivienne is tiny and apart, dressed in virginal white. (Pictured above left: TS Eliot and Virginia Woolf by Lady Ottoline Morrell)

It was no accident that the Woolfs called on Freud in his Hampstead house, that her brother Adrian (and his wife) became psychoanalysts, and we see a photograph of Freud in his Hampstead study. Here too is Duncan Grant’s cousin, and Lytton Strachey’s brother, James, portrayed in Grant’s portrait in precise yet casual mode, long legs stretched out as he almost slumps in his chair, his hand resting on a pile of books. James Strachey was to be the first and most influential translator of Freud into English, all 23 volumes of it. Messed-up yet almost hilariously productive lives were a speciality of the group: here are photographs of TS Eliot in a buttoned-up suit, next to Virginia; in one his infamously mad wife Vivienne is tiny and apart, dressed in virginal white. (Pictured above left: TS Eliot and Virginia Woolf by Lady Ottoline Morrell)

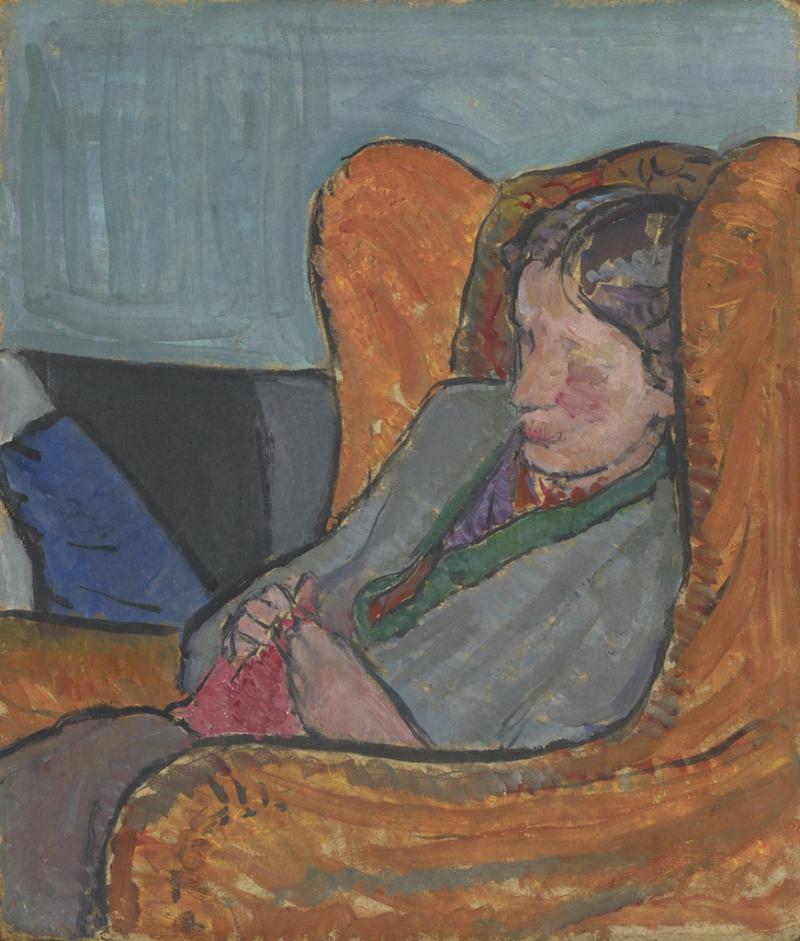

Two parallel portraits of Virginia by Vanessa from 1912 make the contradictions and paradoxes of the writer’s character – the unknowable persona of herself and others about which she was to write so vividly and memorably – strikingly apparent. In one she is embraced by an armchair, a piece of crocheting in her lap, wearing an old lady’s cardigan, her facial features almost entirely obliterated (main picture). In the other she is in front of a table, manuscript or book open in front, her luminous eyes looking out obliquely at something we cannot see, her beauty poignant and wholly memorable.

We see Virginia dressed up for Vogue, fashionable indeed; we see her wearing an ill-fitting dress of her beloved mother’s; and we see her indifferent to appearance, looking like a slightly demented spinster schoolteacher. She is a woman for all seasons. One of Virginia’s best known essays – about women, about writing – is A Room of Her Own. The National Portrait Gallery has justly given her just that – indeed, several rooms of her own. She was known to be a gossip, a beauty, difficult, even impossible, malicious and mesmerising, terrifying and irresistible, hardworking, maddening and maddened. She was not only talented, but an unexpected genius in her way. In so far as this can be made visible, this glorious exhibition distills and communicates a triumphant and tragic character.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Add comment