Still Shocking - The Rite of Spring 100 Years On | reviews, news & interviews

Still Shocking - The Rite of Spring 100 Years On

Still Shocking - The Rite of Spring 100 Years On

Nearly 200 versions have tried to follow Nijinsky and Stravinsky's impact in 1913

Victims driven to death by the mob, women and men violently rutting in animal costumes, a black comedy about a snatched baby, a naked man dancing alone in his own fantasy - many and varied are the images in the nearly 200 danceworks created to the notorious Rite of Spring since its premiere exactly a century ago.

Nothing created in performance art in the 100 years since has had so decisive an aftermath as this seismic work. Nothing has liberated creators from rules quite as emphatically as the uncategorisable theatre piece put before shocked audiences in Paris and London in the late spring of 1913.

Igor Stravinsky's harsh ballet score changed ears, and with it his choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky changed eyes. Is it a ballet or a piece of music? Is it proto-punk agitprop or a gigantic PR stunt? Does it matter? The fact is that a work performed only eight times threw together music, dance, thought, art, instinct, the exhaustion of the old, the reaching for the new, in a clash so fresh and primally frightening that its audience lost control of itself, let its veneer of civilisation slip, and threw missiles at the stage as if defending itself from invasion by devils.

One hundred years on and it still demands the utmost from choreographers, and more than many listeners can give, but its hold on creative artists hasn't slackened. Choreographers great and small have tackled the music's rhythms, the theme's violence, and the myth - above all, the myth of a night when everything was thrown up into the air and landed in a different pattern.

Newspapers called it 'Le Massacre du printemps'. Diaghilev’s satisfied comment was, 'Exactly what I wanted'

This weekend in Moscow the Bolshoi Ballet have launched a terrific festival for the centenary of a piece Russians never saw, though it emerged from the fertile minds of four Russians. Three of the most significant of the 190+ stagings are being shown there: the superb 1975 one by Pina Bausch - probably the greatest of the past 50 years - Maurice Béjart's effective primitivist rout, and a dubious attempt made to reconstruct the lost Nijinsky version from photographs and drawings. There was to have been a new Rite by Britain's own Wayne McGregor over there, only the vicious attack on the Bolshoi's artistic director Sergei Filin made working circumstances impossible, so instead there is another first out there - Russian modernist Tatiana Baganova has made her debut in the Bolshoi at very short notice.

Meanwhile in Britain Sadler's Wells leads the celebratory tribes: the week after next Michael Keegan-Dolan's Fabulous Beast company returns with his Irish-animalistic sex ritual, and in late May Akram Khan tackles the subject in a world premiere ITMOi (the letters stand for "In The Mind Of igor"). The London connections are apt - the English capital was one of only two cities to see the phenomenal work that seized both its own time and the future in one avid grasp.

It was the year before the First World War began, and a startling year in art. It was the year of D H Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers and Marcel Proust's A la recherche du temps perdu, the year that Niels Bohr applied quantum theory to the atom, the year in which Pablo Picasso made his revolutionary Guitar and Marcel Duchamp the first "readymade", Bicycle Wheel. And, four years after his first foray out from Russia, the adventurous impresario Sergei Diaghilev was by now acquiring legendary status for his Ballets Russes, a freelance company of geniuses such as the ballerina Anna Pavlova, choreographer Michael Fokine and house composers Ravel, Debussy and Stravinsky. But of no one, probably, was more being said than about the very young man who had joined Diaghilev on his expedition (and in his bed) at the age of 19, and who by 22 was the most brilliant male dancer of his era.

Vaslav Nijinsky was small, with heavy legs and an odd, peasant face, and an equally awkward manner in company. Yet when he possessed the stage in Fokine’s ballets (then seen as radically new), he underwent inexplicable transformations - from romantic (Les Sylphides) to pathetic (Petrushka). His jumping ability appears to have defined all reality. In most ways he was a figure of mystery.

His first choreography was the short but unforgettable L’Après-midi d’un faune in 1912, in which he harked back to ancient Egyptian art offering a peculiar new kind of hieratic movement with feet parallel rather than turned-out ballet-style. It astonished viewers - although they were more upset about the openly masturbatory ending.

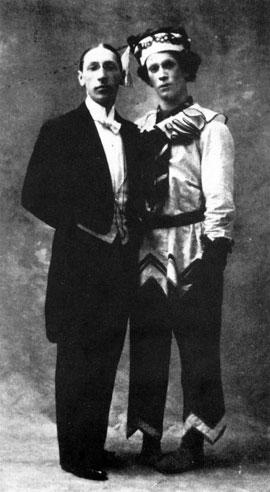

Delighted, Diaghilev urged his fast-rising composer Stravinsky to develop his latest piece into a huge orchestra work for Nijinsky to choreograph, about a primitive ritual culminating in a human sacrifice (Stravinsky and Nijinsky, in Petrushka costume, pictured together). Fokine had quit, jealous at his young star’s threat to his own position. This relieved Stravinsky: “New forms must be created, and the evil, the gifted, the greedy Fokine has not even dreamed of them,” he wrote to his mother in 1912.

Delighted, Diaghilev urged his fast-rising composer Stravinsky to develop his latest piece into a huge orchestra work for Nijinsky to choreograph, about a primitive ritual culminating in a human sacrifice (Stravinsky and Nijinsky, in Petrushka costume, pictured together). Fokine had quit, jealous at his young star’s threat to his own position. This relieved Stravinsky: “New forms must be created, and the evil, the gifted, the greedy Fokine has not even dreamed of them,” he wrote to his mother in 1912.

Now a 22-year-old one-ballet wonder would take over Stravinsky’s monster score - along with a new Debussy piece called Jeux. (The hungry Diaghilev wanted two successes, not just one, for his summer season in Paris and London.)

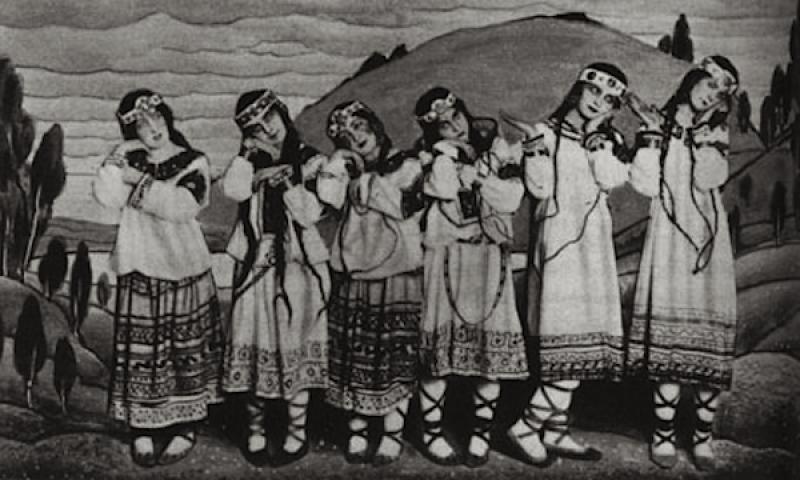

If Stravinsky saw Sacre as his decisive break with the melodious tradition of Rimsky-Korsakov, for the nervy, unstable Nijinsky the choreography was an almost blind journey into the unknown. Using every note and phrase of the composer’s astounding sounds, Nijinsky intended to make a barbaric vision that threw out civilised beauties and showed a pagan mob whipping themselves into a frenzy, with pigeon-toed movements that had no recognisable connection with ballet or even with folk-dance.

Diaghilev’s dancers loathed performing it. The audience’s reaction at Paris’s brand-new Théâtre des Champs-Elysées at the premiere on 29 May 1913 was polarised. Lulled by the opening ballet, Fokine’s delicate Les Sylphides (revolutionary in its own subtle way), they were jolted after the interval by Sacre’s quavery opening cry of a bassoon, moaning like an animal in pain - and then battered by a percussive rhythmic assault like nothing they had heard or seen before. Hostile shouts drowned the music, and the deafened dancers continued only by watching the ashen Nijinsky gesturing from the wings. Police were called to throw out the more violent objectors in the short pause between the score's two parts.

On the other hand, there was the likes of Jacques Rivière, editor of La Nouvelle Revue Française, who enthused: “If we can but stop associating grace with symmetry and arabesques, we shall find it everywhere in Le Sacre du printemps. This is not the usual spring sung by poets, with its breezes, its bird song, its pale skies and tender greens. Here is nothing but the harsh struggle of growth, the panic terror from the rising of the sap, the fearful regrouping of the cells.”

On the other hand, there was the likes of Jacques Rivière, editor of La Nouvelle Revue Française, who enthused: “If we can but stop associating grace with symmetry and arabesques, we shall find it everywhere in Le Sacre du printemps. This is not the usual spring sung by poets, with its breezes, its bird song, its pale skies and tender greens. Here is nothing but the harsh struggle of growth, the panic terror from the rising of the sap, the fearful regrouping of the cells.”

Richard Buckle, Nijinsky’s biographer, observed drily: “The bejewelled Parisian public of the stalls and boxes did not go to the Russian Ballet to watch the regrouping of cells.”

The writer and avant-gardist Jean Cocteau descried a certain amount of Diaghilevian manipulation of the whole thing: "All the elements of a scandal were present," he wrote in his cultural pamphlet Cock and Harlequin. "The smart audience in tails and tulle, diamonds and ospreys, was interspersed with the suits and bandeaux of the aesthetic crowd. The latter would applaud novelty simply to show their contempt for the people in the boxes... Innumerable shades of snobbery, super-snobbery and inverted snobbery were represented... The audience played the role that was written for it."

The newspapers dubbed it “Le Massacre du printemps”. Diaghilev’s satisfied comment was, “Exactly what I wanted.” And yet within weeks - after just a handful of performances in Paris and London - he threw the ballet out, incandescent when his beloved boy announced his marriage to a blue-blooded company groupie. The dancers gratefully forgot the work, leaving no note or memory of the choreography.

Sacre was the high point for its begetters. Nijinsky would go mad, Diaghilev played safer in future, and Stravinsky’s standing as one of the century’s most influential musical geniuses stems from this pivotal creation.

Even 100 years on, the score retains its ruthless capacity to disturb the concert public, despite being the touchstone for all modern music, foreshadowing rock, punk, jazz and world music too. It destroyed the old order, and today we live sometimes uncomfortably with our resultant uncertainty as to where the “classical” and “popular” categories divide.

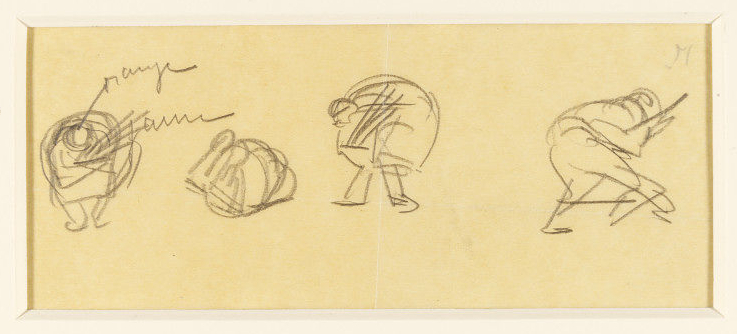

As for Nijinsky’s dance - we can’t assess it, not even from a dubious attempted reconstruction by the Joffrey Ballet in the 1980s, because we do not have the 1913 record, and we do not have the 1913 eyes. (Above, Nijinsky's movements sketched in performance by his contemporary Valentine Gross in 1913, courtsey V&A Museum)

As for Nijinsky’s dance - we can’t assess it, not even from a dubious attempted reconstruction by the Joffrey Ballet in the 1980s, because we do not have the 1913 record, and we do not have the 1913 eyes. (Above, Nijinsky's movements sketched in performance by his contemporary Valentine Gross in 1913, courtsey V&A Museum)

But Richard Buckle wrote: “I am convinced that even Diaghilev and Stravinsky did not entirely appreciate the power of Nijinsky’s Blake-like vision, or recognise how far ahead of his time he was, and I acclaim Le Sacre not only as a masterpiece [...] but also as a seminal work, a turning point in the history of the dance, the ballet of the century.”

Nearly 200 Rites of Spring productions have been choreographed since, but it was Nijinsky’s vision that cracked the perfect egg of classicism, allowing it to hatch new modern fledglings, from Martha Graham to Bausch to Michael Clark to Klaus Obermaier. What is indelible, finally, is the way that May night reminded the world of the dangerous liberating force that theatre had come near to forgetting it possessed. Nijinsky and Stravinsky, inspired in parallel, seized the chance to show not the familiar but the unknown when the curtains parted. That moment, curtain-up, is the instant in which for a second our hearts lurch, as we wonder whether we will see what we know or be led into darkness, reliant on someone else’s alien images.

The images of Le Sacre du printemps may now be wraiths in faded photographs, yet the event of the summer of 1913 has never been surpassed as a triumphant declaration of theatre’s awesome power.

Next page: Choreographers Paul Taylor, Kenneth MacMillan, Martha Graham, Javier de Frutos and Michael Clark on the challenges of making a Rite of Spring. And conductor Michael Tilson-Thomas, Stravinsky's student, talks of the risk of over-familiarity

Above: Malou Airaudo leads Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch in the Sacrificial Dance from Pina Bausch's 1975 Sacre du Printemps

Choreographers on The Rite of Spring

Paul Taylor

The American choreographer, now 82, created two Rite of Springs, one 'interim' version in 1963 (see below) and his enduringly popular 1980 Le Sacre du printemps (The Rehearsal) about a baby snatched by robbers. His company performs it this year on US tour (Pictured right, courtesy PTDC)

The American choreographer, now 82, created two Rite of Springs, one 'interim' version in 1963 (see below) and his enduringly popular 1980 Le Sacre du printemps (The Rehearsal) about a baby snatched by robbers. His company performs it this year on US tour (Pictured right, courtesy PTDC)

"[Clarence Jackson] agreed to write the music [for a new dance] but said it couldn't be ready for at least four months... In the interim I'm setting the dance to Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, a record of which has been lying around the studio for years. Will transfer the dance to Jack's score when it arrives. To some folks this may seem a puzzling modus operandi, but it's logical enough to me. Not following music is a major element in my search for musicality... Steamed up from radiating bodies and a hellish New York summer, the studio mirrors are framing a group of fuzz-edged Rorschach ink blots. The clarity of a contorted dance is being warped... Midget Twyla [Tharp] gleefully bounds and slashes through space. Her piping voice can easily be heard over The Rite of Spring's din. "One-ee-and-ee! Two-ee-and-ee!..." She has become dissatisfied with the counts that I've given her and is counting quadruplets in her own way...

"Two more weeks pass while the dance gains a bonanza of atrocious imagery. While portraying lost souls in limbo we're beset by imaginary hurricanes and pseudofloods. Leaning into the wind, our limbs nearly wrenched from their sockets, we partake of true angst and wallow knee deep in real discomfort. During the long nights between rehearsals I feel porous and pregnable; in the quiet empty spaces before the dancers arrive, an oppressive listlessness comes over me, cold sweats, and spells of dizziness...

"After the dance is over, the audience for the most part are very nice about it. Some of them tell me that they themselves have taken part in similar kinds of performances, or at least they have in their worst nightmares. They can relate; they can sympathize; they wish us better luck next time. Exactly 10 years after the premiere... Charlie comes backstage and hands me a package: 'Here you go, sport. It's the score. Better late than never.'"

Javier de Frutos

The London-based Venezuelan, 50 this year, has choreographed four Rite of Springs: for himself Consecration (1991), The Palace Does Not Forgive (1994) and Sacre (2002), and a year later Milagros for Royal New Zealand Ballet (pictured right by Ross Brown)

The London-based Venezuelan, 50 this year, has choreographed four Rite of Springs: for himself Consecration (1991), The Palace Does Not Forgive (1994) and Sacre (2002), and a year later Milagros for Royal New Zealand Ballet (pictured right by Ross Brown)

"The first three were solos - I felt I needed to get it under my skin before I passed it on to anybody else. With Rite, the idea is mythical - Nijinsky counting like mad in the wings, and the beating of it. I felt that the only way to approach it differently was to be more visceral. Both of the first ones started dressed, and then layers came off - all very pretentious, I think! But the stripping was an idea of taking layers off until you end up vulnerable, as the sacrificial virgin.

"In The Palace Does Not Forgive... the punchline was that this was a sacrificial virgin who decided to question why she had to be sacrificed, and somehow the audience turns - it may sound better on paper - into a jury who decides. Thinking back, I think it was something about not wanting to follow the original scenario. Foolishly, I think, because the music is so extraordinary that you always end up at the end with a sacrifice. You can't get away from something really big that has to happen at the end of this ritual. The music is going to drive you there, whether you like it or not. That's why I like it, because the music leads you so inevitably to that."

Michael Clark

The Scottish dancemaker, 50, choreographed Stravinsky's score in 1992 as Mmm... - also standing for Michael's Modern Masterpiece (Pictured right, © Hugo Glendinning). Also incorporating rock music, it became one of a trio of Stravinsky danceworks by Clark.

The Scottish dancemaker, 50, choreographed Stravinsky's score in 1992 as Mmm... - also standing for Michael's Modern Masterpiece (Pictured right, © Hugo Glendinning). Also incorporating rock music, it became one of a trio of Stravinsky danceworks by Clark.

"Whenever I've heard the music I've been sitting there imagining my own. Couldn't help it. Reworking steps in my head. I imagine when it was written, think what a difficult job Nijinsky had - what sounds lyrical to us now must have been so entirely different in impact then. What choreographer could match that music? Of course the rhythmic bits are what you remember, because they're so powerful. But what I loved about Rite was that the necessity to dance is built into the subject-matter of the piece. Finding that sense of purpose is an ongoing thing in any choreography - why do we bother? There has to be a purpose. But Stravinsky chose to build the subject-matter into the music, and that was kind of exciting.

"Also the idea of sacrifice is such a familiar one to any artist, and dancers, I think, can really relate to it. When I did it first, there weren't any suicide bombers around, and it seemed like such an alien thing to make any kind of sacrifice for something larger than oneself, you know what I mean? But it was just before the First World War when Stravinsky did this, wasn't it?"

Martha Graham

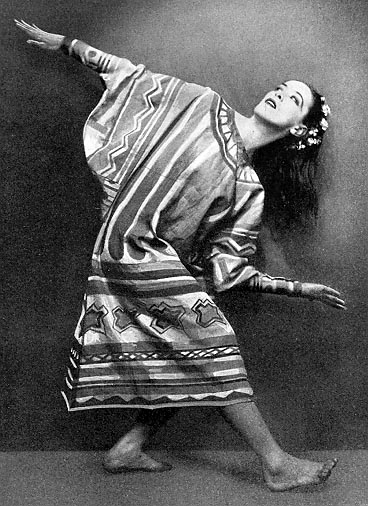

The American pioneer modernist danced The Chosen One in Léonide Massine's 1930 version (Graham pictured right as L'Élue), created her own company version in 1984.

The American pioneer modernist danced The Chosen One in Léonide Massine's 1930 version (Graham pictured right as L'Élue), created her own company version in 1984.

"When you have to do the same movement over and over, do not get bored with yourself, just think of yourself as dancing toward your death. In The Rite of Spring, when I danced the Chosen One, as I did so many continuous times, and came to my moment of finality, I thought of my rebirth."

"[In 1930 the conductor Leopold] Stokowski decided that Léonide Massine would choreograph Le Sacre, since he was responsible for the success of the 1920 Paris revival... We agreed to work together. He was reconstructing the ballet and he frankly did not like me. We had many of our rehearsals at the Dalton School. Every time I did my solo he would turn his back on me, which is a big help, you know. During rehearsals, someone commented that Massine and I looked alike - we were both thin and dark and could have been mistaken for siblings. He was generous with me at the start, but after a time he asked me to resign. He thought I was going to fail. His mistress at the time, he felt, would be just right. Nothing could move me to resign. The more he ignored me, the more he came up to me when I was seated on the floor and whispered, 'You should withdraw. You will have a terrible disaster if you are not a classical ballet dancer,' the more I wanted to stay. Stokowski was firm and said I would dance Élue... It was a very trying time for me because I was not accepted. I was an outsider. I did exactly what Massine told me to do. I interpreted nothing of my own except some qualities of emotion."

Kenneth MacMillan

The Royal Ballet's choreographer tackled the score in 1962 - his version has remained a durable part of repertoire at the Royal Ballet and English National Ballet.

The Royal Ballet's choreographer tackled the score in 1962 - his version has remained a durable part of repertoire at the Royal Ballet and English National Ballet.

"After a while you can hum it - it's full of tunes. [I wanted] a primitiveness of my own invention, rather than any attempt at an imagined pre-history... I believe that the actions and feelings that are shown may still be observed in people today...

"[Of the 20-year-old Monica Mason whom he chose as the leading girl] For one thing she has tremendous power... rare in English dancers, who tend to be more elegant and refined. But she has a real athletic quality, which struck me in rehearsal - also she is tremendously musical."

Conducting the score

Michael Tilson Thomas

Having heard Karajan conduct Rite of Spring, it sounded like someone driving through the jungle in a Mercedes with the windows up

The American conductor, 69, is a known Stravinsky specialist, with several acclaimed recordings with the London Symphony Orchestra during his time as its chief conductor 1988-95, and a frequent guest conductor since.

MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS: What's essential to that piece and to Les Noces is the sound of people making music in the village. The music is used in a curious way, to suggest the sound made by home-made instruments, with idiosyncratic, de-tuned scales. The wonderful ecstatic grunting and squeaking that would be made by people going at their instruments with such intensity that they almost destroy them. This suggests the wildness of the performers. And that's why the piece was at first so difficult technically, and then got easier - which then made it difficult again to play.

Because as Stravinsky himself said once, having heard Karajan conduct Rite of Spring, it sounded like someone driving through the jungle in a Mercedes with the windows up. It's so much easier for musicians to play it that they have to work to remember what it is like to be as technically stretched as the composer intended them to be when he originally scored it.

Again, it's totally gestural, totally folkloric. In my case, I heard Stravinsky sing his own music so many times, and always with this gestural sense to it - he would make gestures with his hands to accompany it. There's nothing academic or intellectual about this music, which made the greater shock in Paris...

ISMENE BROWN: The sight of it, or the sound of it, or both?

A few aspects of the sound, but a lot was the sight of it. The piece was done in an orchestral version a few months after the premiere of the ballet and it actually had quite a solid reception. But so great was the scandal of the first occasion that that didn't go away.

Sacre is basically, like so much in his first music, a piano piece; not so much the introduction, but certainly the dance parts, the dance of the Adolescents, the glorification of the chosen one; he said he played these for months on the piano while he figured out how to write it down. Trying to translate an amazing solo performance of a guy seated at an upright piano in a small room in a house in Switzerland - translating that sort of energy into something that could be played by more than 100 musicians in a theatrical setting. Some of the choices he made in his orchestration were ways to get that very punchy, immediate attack he felt under his own fingers. Not to let it get blurred out.

And when you look at the score that he conducted from it is a real palimpsest, more than any other Stravinsky score, full of layer upon later of revised orchestration, some in his hand, some in Monteux's hand, until the very last second they were working on new voices.

Are there many playing versions or just one accepted one?

There are people who could speak to you with endless authority of one semi-quaver or scrape of a gourd and so on... this is almost a speciality of its own. But I think it would be fair to say that pieces with an origin in theatre very often exhibit a number of alternatives. And you can see from some of the version played that in spite of earnest efforts of teams of scholars, something about the origins of the piece creates a permanent haze of variability over some of the choices that are available. But I don't find that a problem. Some people perhaps more literally-minded than I am get quite upset by it.

- Fabulous Beast Dance Company perform Michael Keegan-Dolan's Rite of Spring at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, 11-13 April

- Akram Khan premieres iTMOi, a tribute to Stravinsky's ballet score, at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, 28 May-1 June

- The Bolshoi Ballet's current Rite of Spring Centenary festival (till 21 April) includes the Maurice Béjart and Pina Bausch Rites, performed by their eponymous companies, and Finnish National Ballet in the so-called 'reconstruction' of Nijinsky. A new Bolshoi creation by Tatiana Baganova was premiered last Thursday evening, further performances in Moscow 7 and 8 May

- The Bride and the Bachelors exhibition around Marcel Duchamp is at the Barbican Arts Centre, London, to 9 June

- The LSO and Michael Tilson Thomas perform at the Barbican Hall, London, on 9, 11 & 12 June

- The Royal Ballet performs MacMillan's Rite of Spring in a mixed bill at the Royal Opera House, London, 9-23 November

- Michael Clark Dance Company premieres new work at the Barbican Arts Centre, London, 21-30 November

- IgorFest: Stravinsky and choreography, a comprehensive article by Ismene Brown

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Cinderella, Royal Ballet review - inspiring dancing, but not quite casting the desired spell

A fairytale in need of a dramaturgical transformation

Cinderella, Royal Ballet review - inspiring dancing, but not quite casting the desired spell

A fairytale in need of a dramaturgical transformation

Add comment