The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from the Life of John le Carré, Apple TV+ review - outstanding, intriguing portrait of David Cornwell | reviews, news & interviews

The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from the Life of John le Carré, Apple TV+ review - outstanding, intriguing portrait of David Cornwell

The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from the Life of John le Carré, Apple TV+ review - outstanding, intriguing portrait of David Cornwell

Errol Morris's film puts the author in a hall of mirrors where the truth is satisfyingly elusive

When the Oscar-winning documentary-maker Errol Morris sat David Cornwell down before his Interrotron camera in 2019, the first salvo of the chat came, not from the interviewer, but from his subject: “Who are you?”

By which Cornwell meant, who does Morris see as the audience for this interview and what are its ambitions? By the end of the film, it will also be clear that Cornwell’s question carried an even weightier payload than that.

It was to be the last filmed interview by the author known as John le Carré, conducted over four days the year before he died, at 89. Even fans steeped in interviews he had done before will be surprised at its richness. Some of its content is familiar from his 2016 essays about his life, The Pigeon Tunnel, extracts from which we hear him reading. But what is startling is watching his performance as an interviewee – a situation whose techniques, he notes, are close to the interrogations he trained in as a member of the Secret Service, and also practised by Morris over the years of his career as an investigative film-maker and private detective. It's spy versus spy.

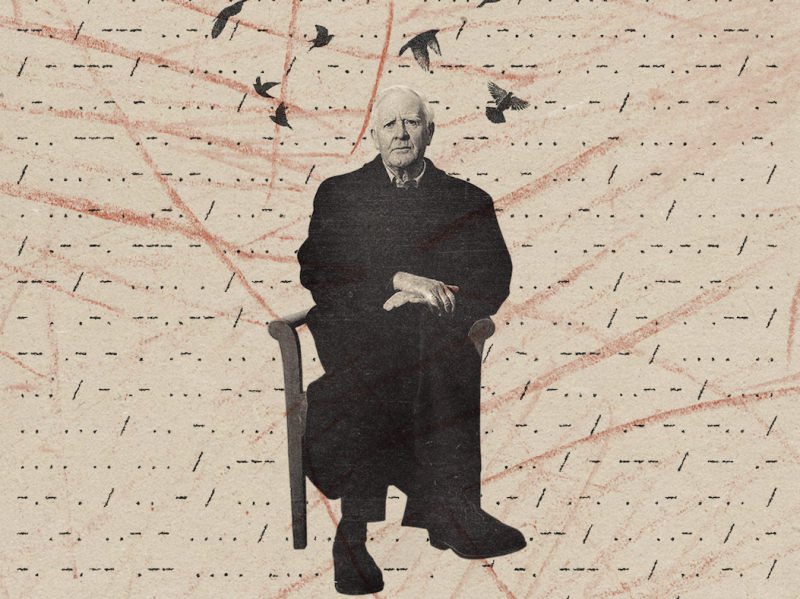

What Morris intends to create around his subject is a hall of mirrors, in which aspects of Cornwell’s life story and the characters he created dance around each other, throwing up parallels. Accompanying the opening is a key shot of Cornwell standing in an overgrown garden but with little images of himself in the foliage, reflecting back at him. Cornwell cannily understands this is the game that's afoot, nudging some questions aside, answering others with astringent candour. And he understands Morris’s approach because, he explains, it is effectively the way he creates a new novel.

It’s exhilarating to hear Cornwell describe this process: a gradual edging towards self-understanding via his characters, all of whom contain a small piece of himself. Psychoanalysis, he observes, was never an option for him as it would have provided too many answers, robbing his fiction of material to feed on. Hence his initial question to Morris: doesn’t he do the same thing, use his films to find out, bit by bit, who he is?

Over the 90 minutes, Cornwell revisits key moments in his life, most filed under "Betrayal". From the day when he was five and his mother left home, sick of her fraudster husband Ronnie, to the great betrayals of the Cambridge spies, to his own betrayals of his two long-suffering wives (not a topic he agrees to go into here), he paints a portrait of himself as doing all in his power to avoid being a “dupe”, like his friend Nicholas Elliott, the pal of Kim Philby sent to confront him in Beirut and, in Cornwell’s strongly held view, to allow him to escape to the USSR.

He admits he polished his act to become one of a class to which he didn’t belong, dressing like them, talking like them. He demonstrates his expert mimicry to Morris, imitating Elliott’s clipped Etonian insouciance, and a Russian official’s blundering attempt to introduce him to Philby. HIs choice of reading modern languages at Oxford, rather than law, seems inevitable.

But one of Morris’s “mirrors" is to get him to talk at length about his father. Which leads Cornwell to suggest that Ronnie and the spies had the same mentality: of wanting to be top-dog by always being “onstage”, addicted to the joys of playing other people and betraying them. And Cornwell too? He admits he understands the “voluptuousness” of this behaviour and that he relates to Philby’s desire to turn his back on his origins. But he had found a safer place for his “larceny”: his stealing of events he had experienced to recycle them into fiction. Writing is the only time he is ever really happy.

But one of Morris’s “mirrors" is to get him to talk at length about his father. Which leads Cornwell to suggest that Ronnie and the spies had the same mentality: of wanting to be top-dog by always being “onstage”, addicted to the joys of playing other people and betraying them. And Cornwell too? He admits he understands the “voluptuousness” of this behaviour and that he relates to Philby’s desire to turn his back on his origins. But he had found a safer place for his “larceny”: his stealing of events he had experienced to recycle them into fiction. Writing is the only time he is ever really happy.

Did he actually experience these things? You will never be so convinced that the membrane separating fact and fiction is wafer-thin, listening to Cornwell’s description of his mother’s flight. He found a white-hide Harrods suitcase of hers after her death and convinced himself it was the one she took with her when she left. But was it? Does it matter if it wasn’t?

Morris re-enacts many of Cornwell’s “memories” or uses clips of the screen versions of them, to incidental music by Philip Glass and Paul Leonard-Morgan. None is so affecting as the sequence that becomes the controlling image of the film, the pigeon tunnel. It comes from his youthful experience of accompanying his conman father to a hotel in Monte Carlo that held regular shoots on its sea-facing lawn. Pigeons were bred in cages on the hotel roof and then fed into a tunnel leading out to the water. There they would launch themselves into the air, free at last, only to face the guests’ guns. Those who survived would return to their “home”, the cages on the roof. The small square of sunlit freedom at the end of the tunnel is revisited throughout the film, along with a closeup of a pigeon bursting under a hail of shot, the sadness of the sequence becoming almost unbearable,

As Cornwell explains in The Pigeon Tunnel, this was the controlling image of much of his own life, not just the working title for most of his books. It encapsulates his sense of the cruelty and poignancy of the world, an insane chaos with no obvious guiding principle where “the inmost room is empty” and there is only the instinctive impulse to keep struggling to be free.

Two of Cornwell’s sons helped produce this documentary, which is one of his last gifts to his readers. As a record of his inimitable style, a meld of wit, candour and asperity, delivered with a relish for performing as keen as that of any of his spies and especially of his father, it is treasurable, addictive viewing. And as a work of film art, fittingly, it is as masterfully complex as its subject.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

The truth about David

The truth about David Cornwell aka John le Carré seems to be that despite being a brilliant author and the undisputed emperor of the espionage fiction genre, he was an imperfect spy. He had more Achilles heels than he had toes and was caught out by Kim Philby.

An interesting "news article" dated 31 October 2022 exists about some of his perceived shortcomings in this regard (pardon the unintentional quip). It's entitled Pemberton's People, Ungentlemanly Officers & Rogue Heroes and can be found on TheBurlingtonFiles website.

While visiting the site do check out Beyond Enkription. It is an intriguing unadulterated and noir fact-based spy thriller and it’s a must read for espionage cognoscenti but what would it have been like if David Cornwell had collaborated with Bill Fairclough? Even though they didn’t collaborate, Beyond Enkription is still described as ”up there with My Silent War by Kim Philby and No Other Choice by George Blake”. Not surprising really - Fairclough was never caught.