Q&A special: The making of Local Hero | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A special: The making of Local Hero

Q&A special: The making of Local Hero

As it becomes a stage musical, the film's writer-director and stars recall the birth of a masterpiece

Local Hero, released in 1983, has been adapted into a musical, with a book by playwright David Greig and more songs from the soundtrack's original composer Mark Knopfler. After its premiere at the Royal Lyceum in Edinburgh, it will arrive at the Old Vic in 2020. No British film from the Eighties can lay claim to quite such lasting and deep-seated affection as Bill Forsyth’s modest masterpiece – not even Chariots of Fire, which was David Puttnam’s previous triumph as a producer. Though not a great commercial success at first – it had a limited release in America – it went on to bloom on VHS and DVD. It also has an asteroid named after it (the 7345 Happer, for the record).

The film was brought back into the light all over again a few years ago when Donald Trump’s plan to plant a golfing resort on a pristine strip of Aberdonian coastline hit a glitch. In Forsyth’s film, a Texan oil company’s attempt to buy up a whole Scottish village is thwarted by a lone white-haired beachcomber (played by Fulton Mackay). Sadly Trump did not turn out to be as human as Burt Lancaster’s Felix Happer and the result is there for all to see in You’ve Been Trumped.

Half of the film was shot just up the road in the tiny port of Pennan - nowadays known, according to undiscoveredscotland.co.uk, as the home of “Scotland’s most famous phone box”. The other half was filmed on the west coast around Arisaig. The result of this bi-coastal shoot is that the village in Local Hero is a geological impossibility.

All I knew about Houston was how to pronounce it

I first saw Local Hero as a school-leaver in 1983, and it has been in residence in my cerebral cortex ever since, alongside Mark Knopfler’s bitter-sweet acoustic theme. On initial viewing it seemed merely a comic gem. The joke was that the village hicks, led by local fixer Gordon Urquhart (Denis Lawson), are far cannier than they appear to Macintyre (Peter Riegert), a cocksure emissary from Knox Oil in Houston sent to negotiate the purchase of the village and its coastline. The older you get, the more it looks like the bleakest Nordic tragedy: having fallen in love with this bucolic paradise, the incomer is brutally expelled from Eden back to the snazzy all-American inferno of skyscrapers and tailbacks, with only sea shells and snapshots as mementoes.

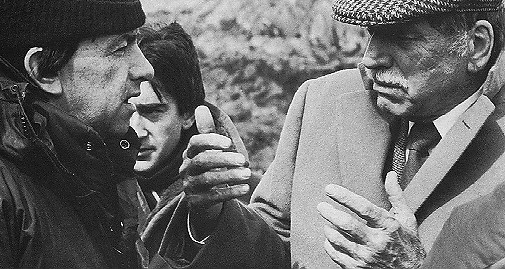

In recent years its environmental credentials have crystallised into what now looks like a timely sermon about our over-reliance on oil. Knox Oil mogul Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster) choppers in like a deus ex machina to close the deal, only to come up against old Ben, the wise man of the beach who persuades him to switch from oil to astronomy. (Pictured right, Lancaster standing on set with Fulton Mackay; in front from left, Peter Capaldi, Peter Riegert and Christopher Rozycki.)

In recent years its environmental credentials have crystallised into what now looks like a timely sermon about our over-reliance on oil. Knox Oil mogul Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster) choppers in like a deus ex machina to close the deal, only to come up against old Ben, the wise man of the beach who persuades him to switch from oil to astronomy. (Pictured right, Lancaster standing on set with Fulton Mackay; in front from left, Peter Capaldi, Peter Riegert and Christopher Rozycki.)

It was in Gregory’s Girl, his no-budget comedy about teenage angst, that Forsyth first paraded a taste for off-beat whimsy. (Previously he had made his living in documentaries.) In Local Hero he quietly folded that quirky voice into a capacious narrative about sea and sky (hence the two main female characters named Marina and Stella) but also the tectonic plates of the Cold War. By night the northern lights twinkle benignly in the heavens which by day swarm with NATO test-jets, while the ancient waters yield lobsters, embargoed South African oranges and a hearty trawlerman from Murmansk, who boats in to sing at the ceilídh and check on his investment portfolio. This colourful character was no fanciful invention. Ditto the plot’s other fish out of water, the parish’s West African vicar.

Local Hero’s success brought Forsyth the chance to make three movies in America. He returned disillusioned and, aside from a short in 2009 titled Bill Forsyth's Lifetime Achievement Film, hasn't shot a frame since Gregory’s Two Girls in 1999. But along with Peter Riegert and Denis Lawson, the film’s two male leads, he reminisced with theartsdesk.

Watch the US trailer to Local Hero

BILL FORSYTH

Could you shed some light on the plot’s genesis? In the DVD extras you talk about how Orkney had done a deal with an oil company similar to the one you portray in the film.

It was quite key to the inspiration. It was the chief executive of the Orkney council who negotiated a really really great deal for the whole community when they were developing the oil terminal. It wasn’t just one company. They were negotiating for this oil terminal which they were all going to use and so he realised that he had quite a strong position and he just did incredible things which hadn’t been done before. Got the community a cut of the revenue and social things like take care of libraries and community centres. It was the scenario where a small community made the best use of the power that it had.

There were examples of small communities which had become en masse wealthy. Pig farmers would be driving about in Jensens

The film skirts over the negotiating situation because that was one thing I didn’t know anything about and didn’t care to research too much. I remember thinking, what they hell can they say to each other? But I had spent the previous 10 years making documentaries all over Scotland so had a fairly good feel for the Highlands and Scottish communities and the economic mechanisms that were at work. I was actually pooling a lot of information. One thing we were always trying to counter in these films was that if you weren’t city-based then you were slightly inferior. That wasn’t the reality. Most of the people you encounter from the Highlands – there were a lot of people who worked at sea and you would find people from the outer islands who were broadly travelled and very sophisticated. It was to counter all of that. That’s what Gordon’s character was all about.

How much did you know about Houston before you started writing?

All I knew about Houston was how to pronounce it. I didn’t know anything about the city and how it functioned. I suppose it was in the news in those days. Because of the oil boom and oil companies were coming to Scotland and were in the headlines, I vaguely knew that was one of the bases of the American oil industry. I didn’t research it. I’m not very good at research. I remember somebody once said if you’re making a fictional film about any particular aspect like a business or a way of life all you need is two real facts. You can make up the rest. As much as anyone else I had a vague idea of what an oil executive would be and how he would function. Macintyre is an everyman executive. It’s the idea of people losing their personalities in the glass tower of work. At that time they were in the air - all these questions about how are we conducting our lives: are we losing a sense of ourselves?

So how did you embark on solidifying that idea into a commissioned film?

The deal came before the plot. David Puttnam came to me and said, “I don’t know what you’re doing next but if you can find an idea in Scotland that would involve one or two American characters so we could have a couple of Yanks in it then I could finance it.” Warner had a pick-up deal for anything he was making. I went away and because of the fact that I knew Scotland well and about the oil business I came back with that idea fairly quickly. It was a no-brainer having American oil men in Scotland. I had to write a two- or three-page treatment. I invoked the Beverly Hillbillies. This is boomtown Scotland. At that time there were examples of small communities which had become en masse wealthy. Pig farmers would be driving about in Jensens. I remember a joke at the time. This farmer has got a brand new Rolls Royce and phones up and says, “I can’t get any more than 40 mph out of this.” “What gear are you in?” “I’m just in my dungarees and Wellingtons.” How about casting? It was quite a coup to get Burt Lancaster.

How about casting? It was quite a coup to get Burt Lancaster.

Lancaster was there from the very beginning in my head. I began to write the script for him. There was no one else on the horizon as far as I was concerned. I don’t think I even thought we would get Lancaster. It’s always nice to have someone in mind so you can find a voice for him. It was round about the time of Atlantic City. In those days Hollywood stars really were stars. They were beyond human. I remember in Atlantic City he seemed to be playing a human being. I had read something in an interview he had done around that time. Someone said, “You’ve been acting for 30 or 40 years. Have you any ambitions left?” “I’d like to do some real comedy.”

What are your memories of working with him?

He was quite a lot of fun. He was no trouble at all. There was no ego. He didn’t need an ego because everyone respected him. That was just normal. He was hard-working. Like me he didn’t have a lot of small talk, which suited me fine.

Were any of those Ealing comedies in the back of your mind as you wrote?

I caught up with the films after I made it and people started to invoke Ealing comedies vis à vis my work. It was only then that I went to them to see what they were talking about. I wasn’t trying to emulate them. I was fairly dismissive of them before I had seen them, as you do with any British films. Puttnam had this trick and would phone me up and say go to the [he names a Scottish cinema].” I’m sure he organised the screening of Whisky Galore and It’s a Wonderful Life. I think that was his way of trying to cut off my bleakness at the pass. I’d written a draft and so maybe he was feeling it then. It’s not bleakness. It’s just a sense of realness. How else can you apprehend the world without a sense of realism about it? It’s not an emotional response to the way the world is. It’s an intellectual one and a clear-eyed one.

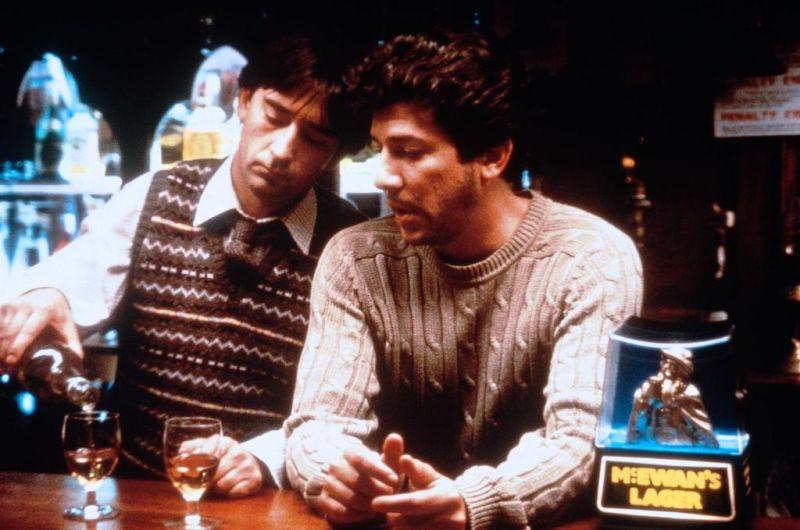

To me and I’m sure to all fans of the film, the casting seems utterly perfect. Did you get your first choice in every case? (Pictured, Jenny Seagrove and Peter Capaldi)

To me and I’m sure to all fans of the film, the casting seems utterly perfect. Did you get your first choice in every case? (Pictured, Jenny Seagrove and Peter Capaldi)

I’m pretty sure I did get my way. I had very good casting help from Suzy Figgis. She was at the spearhead. She was into a lot of fringe theatre in London and knew everyone who was there. Denis was the first choice. For David’s sake he had to show audition reels to the financiers and the studio also I had to go through this process of setting up scenes with actors and filming them more or less to prove that some casting process had taken place. It was a tough tough thing to find Peter. I spent weeks in New York and LA meeting every single actor between 20 and 35 that you could think of. Who did I not meet? One of the people after the part was Michael Douglas. As soon as a film is getting close to production the script just goes all over town. Suddenly we got a call that Michael has read the script and wanted to talk about it. Maybe it’s vanity on my part in those days but I didn’t want any more names in the film. I think at this point I had already committed to Peter. Once again because the finance was involved I had to go through the motions of meeting him and talking to him. That was quite funny too. I was staying at the Holiday Inn in Beverly Hills. I heard the secretary at the office say, “Michael doesn’t eat at the Holiday Inn.” We ended up at the bar at the Beverly Wilshire. I was travelling to New York the day after and checked into my hotel and Michel Douglas walked in. I thought, he’s really after this part. We spent another couple of hours together. It was more just a matter of sitting it out. There wasn’t a huge amount of pressure. It was only a two or three million dollar picture and David carried a lot of authority with the financiers. I do remember a particular point when they were taking a little while to commit to Peter and I said to Peter, “If you don’t do the picture I won’t.” It was genuinely how I felt. I didn’t really know what I was saying. I wasn’t saying it in a political sense.

How was the shoot for you once you assembled this cast? (Pictured, Forsyth on set with Burt Lancaster)

How was the shoot for you once you assembled this cast? (Pictured, Forsyth on set with Burt Lancaster)

It’s true of any film that when you’re writing a script the script becomes limitless in its possibilities but when you’re filming it you’re killing it. We had a good spring. But I wasn’t joining in the fun. It was my first serious film beyond the two that I had made with friends locally. The thing that was catching up with me was that as a writer-director you are the focal point of all the work that goes on. At the end of every single day I would have to go back - I wouldn’t go to the pub - and think about what we’d got, rewrite the scene for tomorrow. It was just continual work. Iain [Smith, associated producer] said, “It’s looking really good but there’s no conflict in it.” I said, “I’m not going to put any conflict in it.” But I remember thinking, he’s right. All these people are just saying things and walking in and out of situations. It was almost for the audience’s sake that something physical had to happen so it was after that that I wrote the scenes where some of the villagers came onto the beach and introduced an element of threat.

The film’s environmental message may be what people take out of it more than they used to be, but back in 1983 it was more overtly a film set during the last days of the Cold War. Your Russian capitalist with marital issues is a wonderful creation. I’d love to hear how that idea came to you. Were you very determined that a comedy about a Scottish fishing village would confront the great political issue of the day and ask for a little peace and understanding?

Because I was writing for Scotland and it was one of these countries that felt slightly inferior, I wanted to up the ante for it. I suppose a very very basic motivation was to let people feel that Scotland had a cosmopolitan aspect to it. That was based in reality. It did happen. There were Russian trawler fleets that operated in the North Sea and the North Atlantic. The Russians used to have factory ships which anchored just off Ullapool. There were times where you would see almost a whole fleet anchored off Ullapool and these guys would come ashore and go to a pub. Apparently they were always quite dour and didn’t talk. At that time in the thick of the Cold War - it was something quite interesting.

How much did you know about the sky before you wrote it?

How much did you know about the sky before you wrote it?

I was a very keen amateur astronomer when I was young and to some extent still am. It wasn’t something I had to think about. I knew what it was all about. When I was writing the script I was also working on a George Mackay Brown ghost story and when filming that was the first time I’d seen the northern lights and that’s why it ended up in the film. The northern lights were created and not too well because special effects in those days weren’t too hot. It used to worry me. There’s a tiny bit of northern lights on the telephone box. They had to mask all the bits where it wasn’t supposed to be.

It’s interesting that Gordon and Stella are at it like rabbits (and Gordon also cooks a tasty rabbit stew) but have no children. Was that strategic?

That hadn’t crossed my mind. We mostly concentrate on Gordon and Stella and they’re pre-children. If kids had been in my horizon at the time they might have ended up in the script.

Overleaf: 'You really want to send them out with a song in their heart - Mark Knopfler's soundtrack

Local Hero, released in 1983, has been adapted into a musical, with a book by playwright David Greig and more songs from the soundtrack's original composer Mark Knopfler. After its premiere at the Royal Lyceum in Edinburgh, it will arrive at the Old Vic in 2020. No British film from the Eighties can lay claim to quite such lasting and deep-seated affection as Bill Forsyth’s modest masterpiece – not even Chariots of Fire, which was David Puttnam’s previous triumph as a producer. Though not a great commercial success at first – it had a limited release in America – it went on to bloom on VHS and DVD. It also has an asteroid named after it (the 7345 Happer, for the record).

The film was brought back into the light all over again a few years ago when Donald Trump’s plan to plant a golfing resort on a pristine strip of Aberdonian coastline hit a glitch. In Forsyth’s film, a Texan oil company’s attempt to buy up a whole Scottish village is thwarted by a lone white-haired beachcomber (played by Fulton Mackay). Sadly Trump did not turn out to be as human as Burt Lancaster’s Felix Happer and the result is there for all to see in You’ve Been Trumped.

Half of the film was shot just up the road in the tiny port of Pennan - nowadays known, according to undiscoveredscotland.co.uk, as the home of “Scotland’s most famous phone box”. The other half was filmed on the west coast around Arisaig. The result of this bi-coastal shoot is that the village in Local Hero is a geological impossibility.

All I knew about Houston was how to pronounce it

I first saw Local Hero as a school-leaver in 1983, and it has been in residence in my cerebral cortex ever since, alongside Mark Knopfler’s bitter-sweet acoustic theme. On initial viewing it seemed merely a comic gem. The joke was that the village hicks, led by local fixer Gordon Urquhart (Denis Lawson), are far cannier than they appear to Macintyre (Peter Riegert), a cocksure emissary from Knox Oil in Houston sent to negotiate the purchase of the village and its coastline. The older you get, the more it looks like the bleakest Nordic tragedy: having fallen in love with this bucolic paradise, the incomer is brutally expelled from Eden back to the snazzy all-American inferno of skyscrapers and tailbacks, with only sea shells and snapshots as mementoes.

In recent years its environmental credentials have crystallised into what now looks like a timely sermon about our over-reliance on oil. Knox Oil mogul Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster) choppers in like a deus ex machina to close the deal, only to come up against old Ben, the wise man of the beach who persuades him to switch from oil to astronomy. (Pictured right, Lancaster standing on set with Fulton Mackay; in front from left, Peter Capaldi, Peter Riegert and Christopher Rozycki.)

In recent years its environmental credentials have crystallised into what now looks like a timely sermon about our over-reliance on oil. Knox Oil mogul Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster) choppers in like a deus ex machina to close the deal, only to come up against old Ben, the wise man of the beach who persuades him to switch from oil to astronomy. (Pictured right, Lancaster standing on set with Fulton Mackay; in front from left, Peter Capaldi, Peter Riegert and Christopher Rozycki.)

It was in Gregory’s Girl, his no-budget comedy about teenage angst, that Forsyth first paraded a taste for off-beat whimsy. (Previously he had made his living in documentaries.) In Local Hero he quietly folded that quirky voice into a capacious narrative about sea and sky (hence the two main female characters named Marina and Stella) but also the tectonic plates of the Cold War. By night the northern lights twinkle benignly in the heavens which by day swarm with NATO test-jets, while the ancient waters yield lobsters, embargoed South African oranges and a hearty trawlerman from Murmansk, who boats in to sing at the ceilídh and check on his investment portfolio. This colourful character was no fanciful invention. Ditto the plot’s other fish out of water, the parish’s West African vicar.

Local Hero’s success brought Forsyth the chance to make three movies in America. He returned disillusioned and, aside from a short in 2009 titled Bill Forsyth's Lifetime Achievement Film, hasn't shot a frame since Gregory’s Two Girls in 1999. But along with Peter Riegert and Denis Lawson, the film’s two male leads, he reminisced with theartsdesk.

Watch the US trailer to Local Hero

BILL FORSYTH

Could you shed some light on the plot’s genesis? In the DVD extras you talk about how Orkney had done a deal with an oil company similar to the one you portray in the film.

It was quite key to the inspiration. It was the chief executive of the Orkney council who negotiated a really really great deal for the whole community when they were developing the oil terminal. It wasn’t just one company. They were negotiating for this oil terminal which they were all going to use and so he realised that he had quite a strong position and he just did incredible things which hadn’t been done before. Got the community a cut of the revenue and social things like take care of libraries and community centres. It was the scenario where a small community made the best use of the power that it had.

There were examples of small communities which had become en masse wealthy. Pig farmers would be driving about in Jensens

The film skirts over the negotiating situation because that was one thing I didn’t know anything about and didn’t care to research too much. I remember thinking, what they hell can they say to each other? But I had spent the previous 10 years making documentaries all over Scotland so had a fairly good feel for the Highlands and Scottish communities and the economic mechanisms that were at work. I was actually pooling a lot of information. One thing we were always trying to counter in these films was that if you weren’t city-based then you were slightly inferior. That wasn’t the reality. Most of the people you encounter from the Highlands – there were a lot of people who worked at sea and you would find people from the outer islands who were broadly travelled and very sophisticated. It was to counter all of that. That’s what Gordon’s character was all about.

How much did you know about Houston before you started writing?

All I knew about Houston was how to pronounce it. I didn’t know anything about the city and how it functioned. I suppose it was in the news in those days. Because of the oil boom and oil companies were coming to Scotland and were in the headlines, I vaguely knew that was one of the bases of the American oil industry. I didn’t research it. I’m not very good at research. I remember somebody once said if you’re making a fictional film about any particular aspect like a business or a way of life all you need is two real facts. You can make up the rest. As much as anyone else I had a vague idea of what an oil executive would be and how he would function. Macintyre is an everyman executive. It’s the idea of people losing their personalities in the glass tower of work. At that time they were in the air - all these questions about how are we conducting our lives: are we losing a sense of ourselves?

So how did you embark on solidifying that idea into a commissioned film?

The deal came before the plot. David Puttnam came to me and said, “I don’t know what you’re doing next but if you can find an idea in Scotland that would involve one or two American characters so we could have a couple of Yanks in it then I could finance it.” Warner had a pick-up deal for anything he was making. I went away and because of the fact that I knew Scotland well and about the oil business I came back with that idea fairly quickly. It was a no-brainer having American oil men in Scotland. I had to write a two- or three-page treatment. I invoked the Beverly Hillbillies. This is boomtown Scotland. At that time there were examples of small communities which had become en masse wealthy. Pig farmers would be driving about in Jensens. I remember a joke at the time. This farmer has got a brand new Rolls Royce and phones up and says, “I can’t get any more than 40 mph out of this.” “What gear are you in?” “I’m just in my dungarees and Wellingtons.” How about casting? It was quite a coup to get Burt Lancaster.

How about casting? It was quite a coup to get Burt Lancaster.

Lancaster was there from the very beginning in my head. I began to write the script for him. There was no one else on the horizon as far as I was concerned. I don’t think I even thought we would get Lancaster. It’s always nice to have someone in mind so you can find a voice for him. It was round about the time of Atlantic City. In those days Hollywood stars really were stars. They were beyond human. I remember in Atlantic City he seemed to be playing a human being. I had read something in an interview he had done around that time. Someone said, “You’ve been acting for 30 or 40 years. Have you any ambitions left?” “I’d like to do some real comedy.”

What are your memories of working with him?

He was quite a lot of fun. He was no trouble at all. There was no ego. He didn’t need an ego because everyone respected him. That was just normal. He was hard-working. Like me he didn’t have a lot of small talk, which suited me fine.

Were any of those Ealing comedies in the back of your mind as you wrote?

I caught up with the films after I made it and people started to invoke Ealing comedies vis à vis my work. It was only then that I went to them to see what they were talking about. I wasn’t trying to emulate them. I was fairly dismissive of them before I had seen them, as you do with any British films. Puttnam had this trick and would phone me up and say go to the [he names a Scottish cinema].” I’m sure he organised the screening of Whisky Galore and It’s a Wonderful Life. I think that was his way of trying to cut off my bleakness at the pass. I’d written a draft and so maybe he was feeling it then. It’s not bleakness. It’s just a sense of realness. How else can you apprehend the world without a sense of realism about it? It’s not an emotional response to the way the world is. It’s an intellectual one and a clear-eyed one.

To me and I’m sure to all fans of the film, the casting seems utterly perfect. Did you get your first choice in every case? (Pictured, Jenny Seagrove and Peter Capaldi)

To me and I’m sure to all fans of the film, the casting seems utterly perfect. Did you get your first choice in every case? (Pictured, Jenny Seagrove and Peter Capaldi)

I’m pretty sure I did get my way. I had very good casting help from Suzy Figgis. She was at the spearhead. She was into a lot of fringe theatre in London and knew everyone who was there. Denis was the first choice. For David’s sake he had to show audition reels to the financiers and the studio also I had to go through this process of setting up scenes with actors and filming them more or less to prove that some casting process had taken place. It was a tough tough thing to find Peter. I spent weeks in New York and LA meeting every single actor between 20 and 35 that you could think of. Who did I not meet? One of the people after the part was Michael Douglas. As soon as a film is getting close to production the script just goes all over town. Suddenly we got a call that Michael has read the script and wanted to talk about it. Maybe it’s vanity on my part in those days but I didn’t want any more names in the film. I think at this point I had already committed to Peter. Once again because the finance was involved I had to go through the motions of meeting him and talking to him. That was quite funny too. I was staying at the Holiday Inn in Beverly Hills. I heard the secretary at the office say, “Michael doesn’t eat at the Holiday Inn.” We ended up at the bar at the Beverly Wilshire. I was travelling to New York the day after and checked into my hotel and Michel Douglas walked in. I thought, he’s really after this part. We spent another couple of hours together. It was more just a matter of sitting it out. There wasn’t a huge amount of pressure. It was only a two or three million dollar picture and David carried a lot of authority with the financiers. I do remember a particular point when they were taking a little while to commit to Peter and I said to Peter, “If you don’t do the picture I won’t.” It was genuinely how I felt. I didn’t really know what I was saying. I wasn’t saying it in a political sense.

How was the shoot for you once you assembled this cast? (Pictured, Forsyth on set with Burt Lancaster)

How was the shoot for you once you assembled this cast? (Pictured, Forsyth on set with Burt Lancaster)

It’s true of any film that when you’re writing a script the script becomes limitless in its possibilities but when you’re filming it you’re killing it. We had a good spring. But I wasn’t joining in the fun. It was my first serious film beyond the two that I had made with friends locally. The thing that was catching up with me was that as a writer-director you are the focal point of all the work that goes on. At the end of every single day I would have to go back - I wouldn’t go to the pub - and think about what we’d got, rewrite the scene for tomorrow. It was just continual work. Iain [Smith, associated producer] said, “It’s looking really good but there’s no conflict in it.” I said, “I’m not going to put any conflict in it.” But I remember thinking, he’s right. All these people are just saying things and walking in and out of situations. It was almost for the audience’s sake that something physical had to happen so it was after that that I wrote the scenes where some of the villagers came onto the beach and introduced an element of threat.

The film’s environmental message may be what people take out of it more than they used to be, but back in 1983 it was more overtly a film set during the last days of the Cold War. Your Russian capitalist with marital issues is a wonderful creation. I’d love to hear how that idea came to you. Were you very determined that a comedy about a Scottish fishing village would confront the great political issue of the day and ask for a little peace and understanding?

Because I was writing for Scotland and it was one of these countries that felt slightly inferior, I wanted to up the ante for it. I suppose a very very basic motivation was to let people feel that Scotland had a cosmopolitan aspect to it. That was based in reality. It did happen. There were Russian trawler fleets that operated in the North Sea and the North Atlantic. The Russians used to have factory ships which anchored just off Ullapool. There were times where you would see almost a whole fleet anchored off Ullapool and these guys would come ashore and go to a pub. Apparently they were always quite dour and didn’t talk. At that time in the thick of the Cold War - it was something quite interesting.

How much did you know about the sky before you wrote it?

How much did you know about the sky before you wrote it?

I was a very keen amateur astronomer when I was young and to some extent still am. It wasn’t something I had to think about. I knew what it was all about. When I was writing the script I was also working on a George Mackay Brown ghost story and when filming that was the first time I’d seen the northern lights and that’s why it ended up in the film. The northern lights were created and not too well because special effects in those days weren’t too hot. It used to worry me. There’s a tiny bit of northern lights on the telephone box. They had to mask all the bits where it wasn’t supposed to be.

It’s interesting that Gordon and Stella are at it like rabbits (and Gordon also cooks a tasty rabbit stew) but have no children. Was that strategic?

That hadn’t crossed my mind. We mostly concentrate on Gordon and Stella and they’re pre-children. If kids had been in my horizon at the time they might have ended up in the script.

Overleaf: 'You really want to send them out with a song in their heart - Mark Knopfler's soundtrack

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Neil Young: Coastal review - the old campaigner gets back on the trail

Young's first post-Covid tour documented by Daryl Hannah

Neil Young: Coastal review - the old campaigner gets back on the trail

Young's first post-Covid tour documented by Daryl Hannah

The Penguin Lessons review - Steve Coogan and his flippered friend

P-p-p-pick up a penguin... few surprises in this boarding school comedy set in Argentina during the coup

The Penguin Lessons review - Steve Coogan and his flippered friend

P-p-p-pick up a penguin... few surprises in this boarding school comedy set in Argentina during the coup

Blue Road: The Edna O'Brien Story - compelling portrait of the ground-breaking Irish writer

Glitz and hard graft: Sinéad O'Shea writes and directs this excellent documentary

Blue Road: The Edna O'Brien Story - compelling portrait of the ground-breaking Irish writer

Glitz and hard graft: Sinéad O'Shea writes and directs this excellent documentary

DVD/Blu-ray: In a Year of 13 Moons

UK disc debut for Fassbinder's neglected, tragic, tender trans tale

DVD/Blu-ray: In a Year of 13 Moons

UK disc debut for Fassbinder's neglected, tragic, tender trans tale

The Amateur review - revenge of the nerd

Remi Malek's computer geek goes on a cerebral killing spree

The Amateur review - revenge of the nerd

Remi Malek's computer geek goes on a cerebral killing spree

Holy Cow review - perfectly pitched coming-of-age tale in rural France

Debut feature of immense charm with an all-amateur cast

Holy Cow review - perfectly pitched coming-of-age tale in rural France

Debut feature of immense charm with an all-amateur cast

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Blu-ray: Yojimbo / Sanjuro

A pair of Kurosawa classics, beautifully restored

Blu-ray: Yojimbo / Sanjuro

A pair of Kurosawa classics, beautifully restored

Mr Burton review - modest film about the birth of an extraordinary talent

Harry Lawtey and Toby Jones excel as the future Richard Burton and his mentor

Mr Burton review - modest film about the birth of an extraordinary talent

Harry Lawtey and Toby Jones excel as the future Richard Burton and his mentor

Restless review - curse of the noisy neighbours

Assured comedy-drama about an ordinary Englishwoman turned vigilante

Restless review - curse of the noisy neighbours

Assured comedy-drama about an ordinary Englishwoman turned vigilante

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Four Mothers review - one gay man deals with three extra mothers

Darren Thornton's comedy has charm but is implausible

Four Mothers review - one gay man deals with three extra mothers

Darren Thornton's comedy has charm but is implausible

Add comment