theartsdesk Q&A: Musicians Robert Plant and Jimmy Page | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musicians Robert Plant and Jimmy Page

theartsdesk Q&A: Musicians Robert Plant and Jimmy Page

Unseen archive interview with half of Led Zeppelin

Since December 2007, the question has been: will they or won’t they?

The band’s founder, Page, has, since Bonham died in 1980 from alcohol-induced asphyxiation, wanted nothing more than to bring Zeppelin back to life. He led the band with a touch of genius for the first seven years, aided by the supreme musical gifts of his three collaborators and a forbidding Svengali of a manager called Peter Grant, before succumbing to an addiction to heroin that almost killed him.

Plant was hit by bizarre misfortune twice in Page’s smack period (the mid-1970s to the early 1980s), first being smashed up in a car accident in 1975, then losing his son to a strange respiratory virus in 1977. After Bonham’s entirely avoidable demise, Plant publicly cast a veil over Zeppelin's grisly late-Seventies decline and, solo, was courageous but musically listless. Jones carved out an on-off career as composer and producer, rarely concerned with re-riding the Zeppelin juggernaut.

Plant has, artistically, long been the "reunion" problem. Hitting 60, he had a massive and wholly unexpected success, with Alison Krauss, with the album Raising Sand, extended three years later by his new, widely acclaimed solo effort, Band of Joy. The singer has found a belated role for himself which arguably places him - a tough thing for diehard Zep fans to stomach - some furlongs beyond even the lightning velocity of his former band (though their music remains incredibly exciting). By all accounts, his relationship with Page blows hot and cold. Page concedes that Zeppelin can only rise again when Plant wants it to - and that’s unlikely to be any time soon…

The members of the most influential British band after The Beatles still hit the news. Plant, made a CBE in 2008, is touring with Band of Joy. Page has put together a photographic book of his career (theartsdesk might add that, as our late colleague Robert Sandall trenchantly noted earlier this year on Radio 4, Page hasn’t come up with a single memorable riff since the band broke up). Jones has been most recently active and most “Zeppelin-like” with a composite band of heavy hitters, Them Crooked Vultures.

In 1998, I interviewed Plant and Page. The immediate peg was a tour they were doing for a CD, Walking into Clarksdale, their first, distinctly below-par effort at co-writing since Zeppelin disbanded: I’d seen them perform songs from it, and a clutch of Zeppelin numbers, a few weeks before on a wickedly rainy night at an outdoor festival in Cologne.

Another focus was Led Zeppelin's first LP being made exactly 30 years earlier. I hoped to get the two men to remember how the band had formed, then cut Led Zeppelin I (pictured right, cover). About it and other matters - though not, alas, the group’s touring anarchy and carnage (I was instructed by the PR not to ask: it'd been mostly John Bonham's anyway) - they were eloquent and pioneeringly free in their memories. They'd not opened up to the mainstream media quite like this in over 20 years - and, infamously, had rarely done so even during Zeppelin's glory years.

Another focus was Led Zeppelin's first LP being made exactly 30 years earlier. I hoped to get the two men to remember how the band had formed, then cut Led Zeppelin I (pictured right, cover). About it and other matters - though not, alas, the group’s touring anarchy and carnage (I was instructed by the PR not to ask: it'd been mostly John Bonham's anyway) - they were eloquent and pioneeringly free in their memories. They'd not opened up to the mainstream media quite like this in over 20 years - and, infamously, had rarely done so even during Zeppelin's glory years.

A few pointers for the Q&A that follows: the “lead balloon” quip refers to the anecdotal naming of the band (as in “going down like a…”, which is what, in 1968, either The Who’s Keith Moon or John Entwhistle reckoned Page’s outfit would amount to). The best albums are I to IV, recorded between 1968 and 1971, followed by Houses of the Holy (1973) and Physical Graffiti (1975). Stephen Davis's 1985 book, Hammer of the Gods, was at the time of my interview still the only half-decent written account of the band - now superseded by Mick Wall's marginally less salacious When Giants Walked the Earth (2008).

Of special interest are Page’s thoughts about the band being captured live on film. What he says here about an apparent lack of footage was disingenuous. Page actually had access to miles of celluloid and went out in the years ahead to find more, much of it unauthorised on Super-8, from hundreds of 1970s concerts: bootleg film. The result, in 2003, was a double DVD set of pure Zep majesty.

The interview took place in north London on 12 October, 1998. It has not appeared in any form until now.

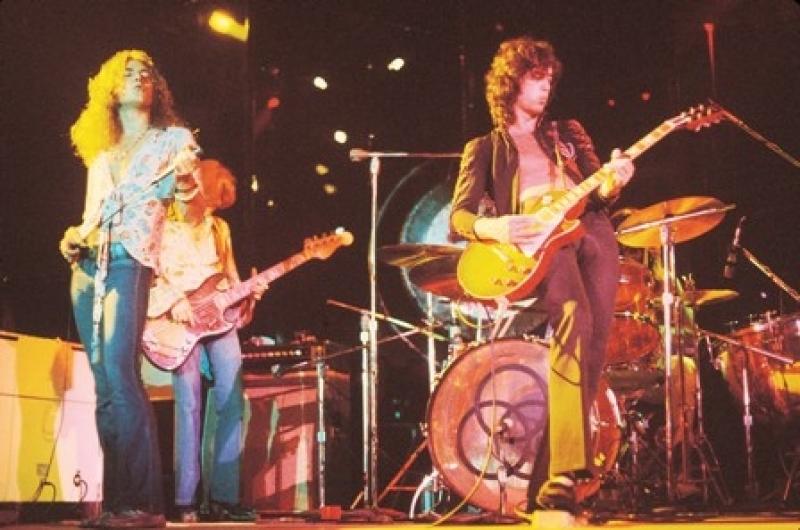

Watch Led Zeppelin play "Dazed and Confused", 1969:

JAMES WOODALL: Can we try going back 30 years, back to the beginning - to the making of Led Zeppelin I?

ROBERT PLANT: We can, you can try. We could try. Weird. Time flies.

What does each of you like to remember about the formation of the band?

JIMMY PAGE: How immediate the whole thing was, just how the four personalities went into this one room and bonded immediately musically, and carried on bonding the whole way through. I mean, that was what it was. That’s it. That is it. There were other people, afterwards, trying to put bands together, this one and that one, and this superstar and that: none of it really mattered at the end of the day. What we had was something very special.

PLANT: Once we could lure Bonzo [John Bonham] away from the gig he was doing… He was busy bringing in £35 a week and on no account was he gonna leave. I kept saying, "You gotta do this, you gotta do this," and he said it was another tinpoint idea of mine, but we got him in the end. I took Jimmy to see him in Haverstock Hill…

PAGE: …Well, yes, the fact is, he didn’t wanna join, did he? We had to coax him into this rehearsal room, but once we got in there, as with all of us, it was so spontaneous and everyone knew what was going on, and OK, that was it, that was the initial spark, and from thereon we developed it. (Below left, an early publicity shot)

And John Paul Jones? PAGE: We’d done a lot of studio work, individually, and occasionally together, so we knew about each other - but I only really knew him well from that point. I remember seeing him playing once on stage with Bo Diddeley, in the backing band, on one of those podiums somewhere or other, but I only got to know him during the studio days.

PAGE: We’d done a lot of studio work, individually, and occasionally together, so we knew about each other - but I only really knew him well from that point. I remember seeing him playing once on stage with Bo Diddeley, in the backing band, on one of those podiums somewhere or other, but I only got to know him during the studio days.

Any clues about the source of the “lead balloon” joke?

PAGE: It was Keith Moon.

I’ve heard it was John Entwhistle. [The Who’s bassist died in 2002.]

PAGE: Oh, I don’t really mind. I mean, all I know is that I heard it from Keith Moon, it could well have been Entwhistle’s joke, it could have been Uncle Tom Cobbley’s, and we could have been called The Potatoes and it still would have happened.

And the making of the album?

PAGE: It took 36 hours in a studio in Barnes, but that’s only collective. I mean, it’s not like we went in there and 36 hours later we came out. It’s just the fact that... I remember paying for the studio bills...

With Peter Grant?

PAGE: No, no, in those days to be honest with you, it was me.

PLANT: I can remember the smell of fear. I was petrified. I couldn’t believe the size of the control room, the size of the room itself, the sound coming through the speakers. When we listened to playbacks, it was unbelievable, fantastic to hear what we'd done in the rehearsal room develop a different perspective and sound, like we know it sounds. It was the most amazing sensation.

The vocal is so achieved. How did you hit that level, which became so unmistakably the Led Zeppelin sound?

PLANT: It’s stated, but it doesn’t have any bend and flow to it which developed later on. By time of “What is and What Should Never Be” and maybe “Ramble On” [both on Led Zeppelin II], I was beginning to create a dynamic within my own performance a bit better. I think the way I was singing then was more like a sort of blue-shadow-stated thing which, you know…

PAGE: ... It fitted.

PLANT: Yeah, it fitted.

PAGE: Absolutely, this is it, this is the gel of the whole thing, because it’s really urgent music, scary stuff. When you look at that album, the amount of ideas and moods and vibes that are on it is really quite something. I suppose that’s why it was so achieved,like its successor.

And Jimmy, did you already have that sound in your head?

PAGE: Well, in a way, yes, but I’ll just put it another way. I’d been a studio musician for many, many years, a whole apprenticeship, and I knew how not to record. I’d been in some quite incredible sessions, in 1964 and 1965 and early 1966, but in some of them, though the sessions were really good, the sound was terrible, where they’d have a drummer in a little room and the drums couldn’t breathe. It was so obvious. The drums really had to breathe, to get the harmonics in: so that was about knowing what to do and what not to do.

But the musical values, in terms of the texture and the quality...

PAGE: Well, I had a clear idea of what I wanted to do. I think Robert would agree…

PLANT: We all came from different angles and we all contributed without any trepidation. I mean, I came out of a band that was playing in clubs with a tiny-weeny PA and you just had to shout all the time basically. But, for me, if you listen to some of Bonzo’s drum work on the first album, it’s fantastic. But he really gets down to business later on in the Led Zeppelin catalogue.

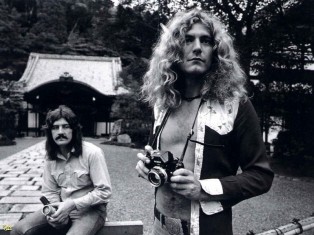

Where, particularly? PLANT: Houses of the Holy, Physical Graffiti, Zep IV. I just think maybe on the first album we were just Black Country kids (pictured right, Bonham and Plant in 1969) who were going, “Fucking hell, what’s this? So I’ll get this really precise” - whereas later on, Bonzo got a bit more relaxed...

PLANT: Houses of the Holy, Physical Graffiti, Zep IV. I just think maybe on the first album we were just Black Country kids (pictured right, Bonham and Plant in 1969) who were going, “Fucking hell, what’s this? So I’ll get this really precise” - whereas later on, Bonzo got a bit more relaxed...

PAGE: As I said to you, the first album, I was paying for that...

£1,800 at the time?

PAGE: ...I can’t remember what it was, but I mean it was one of those things where with my old studio disciplines and John Paul Jones’s, we locked into that thing like we had in the past, so it was done quickly. We still managed to hear playbacks of what we did but it was pretty fast with the overdubs. At a later point in time, obviously, when we could afford to do so, we had a little more time to invest in things. But that urgency worked on the first album.

Any doubts during the making of it?

PAGE: Absolutely not, absolutely not, no, no.

Why do you think there is such intense interest in Led Zeppelin today?

Watch Led Zeppelin play "Whole Lotta Love", Royal Albert Hall, 1970:

PLANT: I suppose it’s just a kind of tapestry of music. There are a lot of variations: the themes change, the moods change. We didn’t actually develop a style and stick to it, we were moving all over the place. People remember that, from those days, and people now who find us, those I’ve met, can’t believe that you can actually cover such a broad volume of alternative areas in one four-piece band. That was the great thing about it. The difference between “Living Loving Maid” [from Led Zeppelin II] and “In the Light” [from Physical Graffiti], you know, “Four Sticks” [from Led Zeppelin IV] ... it’s entertainment, and we purposely set out to please ourselves, and kept changing around. Now, we play the game more. Different days...

When you say “play the game more”, what do you mean?

PLANT: We’re talking to you. There’s nothing wrong with that, but you know what I’m saying. And the name Led Zeppelin now - its use? You continue to play lots of Led Zeppelin numbers… (Left, image used for the 2003 live DVD box set)

And the name Led Zeppelin now - its use? You continue to play lots of Led Zeppelin numbers… (Left, image used for the 2003 live DVD box set)

PAGE: ...Playing the numbers we wrote. And new material. It’s called the fair-trading act, or whatever. It’s who it is, it’s the two of us.

Let me ask you both a blanket question - I’m sure you both have easy answers for it: what do you think about the books which have been written about Led Zeppelin?

PLANT: Shame the people who wrote them had no skill or craft or capacity to write. There’s a lot of cub-reporter stuff, a lot of exaggeration. That’s how it goes with popular music. I read a great book called Hellfire, about Jerry Lee Lewis, and I found that so amazing but I’m sure Jerry Lee was furious.

Were you furious about Stephen Davis’s book [Hammer of the Gods]?

PAGE: I didn’t read much of it.

PLANT: I read the end, to see how we were doing at the time.

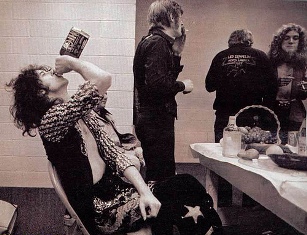

PAGE: It’s a real shame that there are a couple of things that in retrospect there isn’t enough of: one is live footage of us, in some sort of form, apart from The Song Remains the Same [a feature film released in 1976], that was actually done at that point. (Right, Page backstage in the US in around 1975) I’m not talking about something that’s put together now. And at the time, maybe, I think if someone had written a book about the romance of the time, on the road…

PAGE: It’s a real shame that there are a couple of things that in retrospect there isn’t enough of: one is live footage of us, in some sort of form, apart from The Song Remains the Same [a feature film released in 1976], that was actually done at that point. (Right, Page backstage in the US in around 1975) I’m not talking about something that’s put together now. And at the time, maybe, I think if someone had written a book about the romance of the time, on the road…

Would you have allowed that?

PAGE: Probably not. But that’s what I’m saying, in retrospect...

If you’d known.

PAGE: Yeah.

John Bonham’s death: it was clear that there was the likelihood that Led Zeppelin wouldn’t continue and I guess there was general approval of your decision not to replace him. I’ve got three questions around this...

PAGE: But first of all, you’ve just said “replace him”: I mean, I don’t think you could have replaced any single one of us at the time, it just didn’t come into the equation.

But how much did his death underline his particular role in the band?

PAGE: He was without doubt the most creative, powerful, technical drummer that ever lived. It’s as simple as that. That’s it. You don’t go much beyond that, because he was. And he developed his style during the days of Led Zeppelin as much as Robert did or I did. He was an incredibly strong character.

Can you remember now how you felt immediately afterwards?

PAGE: I’d rather not remember how I felt at the time, thank you.

And you feel the same, Robert? After Led Zeppelin, what about Peter Grant (pictured below left)? PLANT: I didn’t really have much to do with him. No, I just kept to myself, from that whole period of my life anyway, for quite a while. I think enough was enough. We’d had a good run. Peter had been instrumental in one of the most amazing success stories for British artists ever; with his common sense, his firmness and his aura, we were phenomenal. But after John passed away, there was no need for me to be around it any more.

PLANT: I didn’t really have much to do with him. No, I just kept to myself, from that whole period of my life anyway, for quite a while. I think enough was enough. We’d had a good run. Peter had been instrumental in one of the most amazing success stories for British artists ever; with his common sense, his firmness and his aura, we were phenomenal. But after John passed away, there was no need for me to be around it any more.

The taboo question - about “Stairway to Heaven”. Can you explain the big cross through that song for you now?

PLANT: I think it’s exhausted. It’s been used. It’s lost its context, for me, because it’s been heralded as the only thing, that that’s our signature tune, if you like, and our work does so many things. It’s also very difficult to perform live, for me. I just feel I’ve grown out of it lyrically, although in construction, as a performance, it’s a splendid song, a splendid piece. The way that that whole thing builds and lifts and swirls... We were talking about the guitar solo earlier, it’s one of the most classic entrances into an amazing finale, it’s brilliant.

PAGE: You’ve seen us in Cologne, you’ve seen our approach to the mix of the Clarksdale and Zeppelin stuff. We’re having a lot of fun with it. We can move the parameters of it. But with “Stairway” I don’t think you could. We couldn’t. It’s not the right vehicle. OK, at the moment we’re employing songs that are vehicles for improvisation. And the thing is, if you just have to do a hackneyed version night after night, it becomes tiresome. We don’t need something that could present itself as a bit of a millstone.

Once you did it once, you’d have to do it again and again?

PAGE: I think you would. So rather than get into a snare, we’ll carry on as we are.

Wouldn’t you love to play that solo live again? PAGE: I probably wouldn’t play it as well.

PAGE: I probably wouldn’t play it as well.

You’ve been touring Europe, but America was a major stamping-ground in the early Led Zeppelin days…:

PLANT: Well, it was known to be, but there were many places we couldn’t play in those days because of various political situations and the instability of a lot of the countries that really enjoyed our music. (Above right, exhaustion setting in in 1977) By the time Zeppelin ended, South America was opening up. Queen went down there and Freddie Mercury said to me, “It’s great, everything’s OK” - because before it was mayhem. Likewise Eastern Europe: because we finished before the breakdown of the communist grip, we weren’t able to go there. Now, we have.

Did you both feel you had to take a back seat in the 1980s?

PLANT: No, not at all. I didn’t. I wanted to be up there - I mean, if I do something, I’m committed to it. So I listened all the time. I don’t know whether we can ever say there’s anything really original about anything that anybody does anywhere in the world, as far as projecting art or music is concerned. So I was looking all the time, and I’m sure Jimmy was too. I was working with a lot of really young guys, making records which sound a little dated now, because I was being swayed by people who were really into the technology that was available at the time, so I made records that sounded like that. There’s so much around. Even in the dark 1980s, when the guitar virtually vanished and Howard Jones was at the helm - even then, there were people like This Mortal Coil, Cocteau Twins, The Jesus and Mary Chain: there was good stuff in the middle of it all.

PAGE: I thought the 1980s was a really sad period, to be honest with you. I thought there were lots of very questionable things that went on. I didn’t really play very much then, by choice, really. I dunno. Some funny haircuts went on, that’s for sure, and I’m as much to blame as anyone else there. But as far as my end of it went, I was still, you know, attempting to graft some reasonable songs, which were guitar-based. I wasn’t really listening to what was going on, because it wasn’t relevant at all within what I was doing. But curiously enough, all of the guitar thing came back through again, didn’t it, at the end of the decade? I might have been listening to some of it to appreciate it, but not taking it on board for myself, because I didn’t see myself in any way fitting in in a fashionable sense.

Was it back to the blues for you?

PAGE: It’s always there, in the roots I’ve had - and I’m sure this’d be exactly the same for Robert: all our collective roots, they just run concurrently through everything, it’s like a common denominator, be it early 1950s rock, be it blues, or Arabic music, or music from all over the world, or whatever. That’s been there right from before we even got together, really.

What kind of musical climate do you think your new collaboration has emerged into? Being more specific, Led Zeppelin has sold [in the States] 63 million albums to date, second only to The Beatles...

PAGE: Is that sales in London?

...and the fourth album alone something like 17 million. Along comes Alanis Morissette and she sells to date 24 million of her first album [Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill was released in 1995]. How do you read that situation, a young star starting out at that level?

PLANT: It’s a pop vehicle she’s riding on, and it’s very easily grasped, and it’s great. She’s just riding... or whoever’s doing it… she’s writing very commercial, poppy songs. There’s a whole genre of performers who’ve not always been the way that they are. But people like Tina Turner, Bryan Adams, that sort of thing - Alanis Morissette, who’s younger and a bit more in your face - are all part of the same gene pool.

PAGE: It must be very, very scary for an artist to come and achieve sales like that, because where do you go from there?

I don’t think you ever did “Ramble On” [from the second album] live during Led Zeppelin years - maybe I’m wrong. But it was really exciting to hear it in Cologne. PLANT (laughs): You wanted to talk about the past. How the hell do we know what we played? It was a miracle we were there!

PLANT (laughs): You wanted to talk about the past. How the hell do we know what we played? It was a miracle we were there!

(Pictured left, Led Zeppelin reforms for one night in 2007)

Finally - the easy one. If you had to choose, just one track, from the Led Zeppelin catalogue, which one would you take to a desert island?

PLANT: I’d like “Please Read the Letter” [from Walking into Clarksdale: it re-emerged in 2007, on Raising Sand], because I’d stick it in a bottle and pop it off from the island, and someone might come and collect me. And if that’s not corny, I don’t know what happened in 1968.

Watch Led Zeppelin play "The Ocean", Madison Square Gardens, 1973:

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Gigspanner Big Band - Turnstone

Third album from British folk’s biggest big band

Album: Gigspanner Big Band - Turnstone

Third album from British folk’s biggest big band

Album: Mark Morton - Without the Pain

Second solo album from Lamb of God guitarist lays down hefty southern boogie

Album: Mark Morton - Without the Pain

Second solo album from Lamb of God guitarist lays down hefty southern boogie

Manic Street Preachers, Barrowland, Glasgow review - elder statesmen deliver melody and sing-a-longs

The trio ran through new songs, obscure oldies and big hits in a career spanning set

Manic Street Preachers, Barrowland, Glasgow review - elder statesmen deliver melody and sing-a-longs

The trio ran through new songs, obscure oldies and big hits in a career spanning set

Album: Rhiannon Giddens & Justin Robinson - What Did the Blackbird Say to the Crow

Finger-picking good

Album: Rhiannon Giddens & Justin Robinson - What Did the Blackbird Say to the Crow

Finger-picking good

Music Reissues Weekly: Motor City Is Burning - A Michigan Anthology 1965-1972

Wide-ranging overview of the US state accommodating Detroit, the ‘rock city’

Music Reissues Weekly: Motor City Is Burning - A Michigan Anthology 1965-1972

Wide-ranging overview of the US state accommodating Detroit, the ‘rock city’

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2025

What Record Store Day exclusives are available this year?

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2025

What Record Store Day exclusives are available this year?

Album: Joe Lovano - Homage

Free-flowing spontaneity

Album: Joe Lovano - Homage

Free-flowing spontaneity

Album: Bon Iver - SABLE ƒABLE

An album of exquisite wonder

Album: Bon Iver - SABLE ƒABLE

An album of exquisite wonder

Primal Scream, O2 Academy, Birmingham review - from anthems of social justice to songs of heartbreak

Bobby Gillespie and Andrew Innes aren’t ready to join the heritage circuit yet

Primal Scream, O2 Academy, Birmingham review - from anthems of social justice to songs of heartbreak

Bobby Gillespie and Andrew Innes aren’t ready to join the heritage circuit yet

theartsdesk on Vinyl 89: Wilco, Decius, Hot 8 Brass Band, Henge, Dub Syndicate, Motörhead and more

The last-standing and largest regular vinyl record reviews in the world

theartsdesk on Vinyl 89: Wilco, Decius, Hot 8 Brass Band, Henge, Dub Syndicate, Motörhead and more

The last-standing and largest regular vinyl record reviews in the world

Tallinn Music Week 2025 review - Estonia’s capital accommodates all flavours of music

The festival where everything appears on an equal footing

Tallinn Music Week 2025 review - Estonia’s capital accommodates all flavours of music

The festival where everything appears on an equal footing

Album: Black Country, New Road - Forever Howlong

A left turn that trades chaos for charm, with mixed results

Album: Black Country, New Road - Forever Howlong

A left turn that trades chaos for charm, with mixed results

Add comment