Interview: Director Peter Brook | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Director Peter Brook

Interview: Director Peter Brook

The British director reflects on theatre life in two cultures

Theatre director Peter Brook is back in London. Brightly, eloquently, he's promoting his new show, in English (most of his work since the 1970s has been in French), currently running at the Barbican: entitled Eleven and Twelve, it's a dense chamber piece exploring a religious dispute in early 20th-century Mali. Quiet, sensitively investigative of an unknown strand of north African faith, it will enlighten some and bore others. Classic Brook?

Well, certainly not redolent of the firebrand deconstructor of the 1960s, who imported an alarming thing called Theatre of Cruelty into mainstream British acting and got Glenda Jackson to strip off; nor especially of the great stage builder of, the visionary technician behind, The Mahabharata (pictured), a nine-hour Indian epic first performed in 1985 in a quarry near Avignon and staged in 1988, in English, at Glasgow's Tramway. Eleven and Twelve is late Brook: the work of a contemplative. And as he's grown older and thought more, notably about violence and tolerance, the antithesis which drives Eleven and Twelve, what he's put on stage has become correspondingly simplified and uncluttered.

Well, certainly not redolent of the firebrand deconstructor of the 1960s, who imported an alarming thing called Theatre of Cruelty into mainstream British acting and got Glenda Jackson to strip off; nor especially of the great stage builder of, the visionary technician behind, The Mahabharata (pictured), a nine-hour Indian epic first performed in 1985 in a quarry near Avignon and staged in 1988, in English, at Glasgow's Tramway. Eleven and Twelve is late Brook: the work of a contemplative. And as he's grown older and thought more, notably about violence and tolerance, the antithesis which drives Eleven and Twelve, what he's put on stage has become correspondingly simplified and uncluttered.

Over the last week, Brook's barely been out of BBC studios (for TV's The Culture Show, and for radio's Start the Week and Nightwaves); newspapers have been swooping down; and, on the first Saturday afternoon of February, he gave to an invited audience at the Barbican's Pit a wise, relaxed, ad-libbed talk about directing. "Do you miss England?" someone asked him at the end. "In all honesty, I do," he replied: he misses the language; the fact that drama comes, as he put it, "from the soil", as opposed to the more rigid mannner by which it arrives in France, in keeping with a culture nervous of demotic graftings on to an overprotected classical tongue. He's long been happy to work in French; but native ties to the culture he grew up in - he was born in Chiswick in 1925 to Russian-Latvian émigrés, with Jewish antecedents - always, when he talks, when you meet him, rise vibrantly to the surface.

So does Brook need any special reintroduction to England? Sure, he hasn't lived in Britain since the 1960s; and following his fabled Royal Shakespeare Company A Midsummer Night's Dream of 1970, he's produced no further work here - except, in 1978, a notorious and much-derided RSC Antony and Cleopatra with Alan Howard and Glenda Jackson (the lately ennobled Patrick Stewart played Enobarbus). And yes, he's been comfortably ensconced outre Manche, and thereby significantly absent from any further shaping of the English stage, since founding his Centre for International Theatre Creation in Paris in 1971.

This has led to lazy mythologising: a view of Brook as a magus "in exile", shunning the barbarities of British showbiz, spinning magic in exotic isolation - otherwise known as the Bouffes du Nord (interior, pictured), an enviably authentic, subsidised 19th-century gem in a tatterdemalion quarter near the Gare du Nord - making toilers in the boggy, commercial Anglo-American theatre field look rather flailing and banal. Amongst old (Brook himself, however professionally indefatigable, is now properly, grandpa old) and, more surprisingly, some young theatre fans, a quasi-religious cult surrounds him: as if his methods, so often ending in luminous results, are charged with Kabbalistic mystery.

This has led to lazy mythologising: a view of Brook as a magus "in exile", shunning the barbarities of British showbiz, spinning magic in exotic isolation - otherwise known as the Bouffes du Nord (interior, pictured), an enviably authentic, subsidised 19th-century gem in a tatterdemalion quarter near the Gare du Nord - making toilers in the boggy, commercial Anglo-American theatre field look rather flailing and banal. Amongst old (Brook himself, however professionally indefatigable, is now properly, grandpa old) and, more surprisingly, some young theatre fans, a quasi-religious cult surrounds him: as if his methods, so often ending in luminous results, are charged with Kabbalistic mystery.

His theatre, but particularly his thinking about theatre, have been accorded the force of prophecy. His first (and best) book, The Empty Space, published in 1968, carried for years, mainly for drama students, the heft of holy writ, in spite of one of its four chapters inveighing polemically against any tilt in theatre towards "holiness". Even the Vicar of Dibley once invoked Brook in front of her baffled am-dram parishioners (though this sounded more like show-off Dawn French, actrice, than silly country-vicar speak). The word "guru", moreover, has been spouted about and around Brook almost as often as the dreaded interrogative "Whose whatever-it-is Is It Anyway?" has been recklessly rolled out in the media, about practically anything, since Channel 4 aired in 1988 the gameshow which spawned it.

His theatre, but particularly his thinking about theatre, have been accorded the force of prophecy. His first (and best) book, The Empty Space, published in 1968, carried for years, mainly for drama students, the heft of holy writ, in spite of one of its four chapters inveighing polemically against any tilt in theatre towards "holiness". Even the Vicar of Dibley once invoked Brook in front of her baffled am-dram parishioners (though this sounded more like show-off Dawn French, actrice, than silly country-vicar speak). The word "guru", moreover, has been spouted about and around Brook almost as often as the dreaded interrogative "Whose whatever-it-is Is It Anyway?" has been recklessly rolled out in the media, about practically anything, since Channel 4 aired in 1988 the gameshow which spawned it.

A more recent, below-the-belt tendency, maybe inevitable in our noisome, super-democratised, celebrity-greedy times, has been to decry Brook's unashamed elitism. During an infamous, decade-old spat, playwright David Hare accused his work of being "a universal hippie babbling which represents nothing but fright of commitment". Hare, arguably himself a hectoring old lefty inimical to poetry in the theatre, was regretful of Brook's apparent abandonment of political belligerence, brilliantly built in to his 1960s experiments, such as Marat/Sade and US.

But this seems to me an acceptable price to pay for the delicate, probing, almost miniaturist studies of human longing and frailty in 1990s works, in French, such as Qui est là? (based on Hamlet), Je suis un phénomène (about synesthesia) and Le costume (about cruelty in marriage under apartheid). Much of Hare's work of the same period feels self-duplicatingly gauche, even stiff, by comparison: he's an exegete, haughty on his polished platform. Brook's an explorer, always moving on; protean - which annoys some.

Then, in The Guardian online in January of this year, a more yobbish assault came from a playwright and a director, both suspiciously unnamed and "young": "he has the best theatrical brain since Brecht," said one, "but he hasn't done anything decent for 20 years, not since The Mahabharata. I blame the French. He's gone mouldy like their cheese." Said the other: "If Brook was to stand and fart for an hour on the stage of the National, you will have people queuing to tell you he is a genius. The myth has killed the man." No one should mind a caricature, of course - and Brook generally brushes off such niggles with Tolstoyan disdain.

Equally, he's irked by, and has never encouraged, the guru tag. Caricature is as distant from reality as canonisation. He likes to talk and communicate; and as far as I've been able to tell, in several interviews since 1992, Brook the man, frailer now than when I first met him, has always been pungently alive. His marbles are not only there. They're clinking together: making new tunes, forging new patterns. He remains wedded to his Paris base but knows, too, that there will be a future there beyond him.

When I talked to him about Eleven and Twelve at the Bouffes, where the play opened in November 2009, he explained what's about to change.

"After the experiments of 1968 and the nomadic work our group had done at that time, it was clear that the Bouffes du Nord was to be our centre. We'd been offered halls here and museums there, but this, the Bouffes, once I'd discovered it with Micheline Rozan [Brook's close film and stage associate from the early 1960s], was beautiful, and right. Soon, we were being asked to come and work in all these other places, opera houses, glamorous theatres and so on; but no, the Bouffes was our home from the moment we found it.

"I've never wanted to work anywhere else since. The conditions here were what I wanted to have, and they've not changed. Next season, we'll do The Magic Flute, in our way, the Bouffes way. My feeling was, in handing over the company as I am doing, to two younger men [Olivier Mantei and Olivier Poubelle], that I wanted to return the theatre back to its origins: it was once a music theatre, and that's what needs to be refound. So this coming year is a transition. Moreover, I don't want to be as imprisoned as I have been, keeping the theatre going on its own. Each year, something is expected of me. I want now to be free of that."

His anchoring in the world of the arts, in the best senses of each word - Brook is an unrepentant internationalist, as versed in music and painting and sculpture as in drama and film - has been uncontested for decades. But it stems from factors both more practical and complex than the cultists or the naysayers dare imagine. An exceptionally restless, radical period in the 1960s, which began with his bringing Brecht to Shakespeare in a pioneering RSC King Lear in 1962, with Paul Scofield (pictured), and ended with the phantasmagorical Dream, had to be refreshed into something both less febrile and more expansive: Brook was 45, quite famous, fiercely ambitious; but he had two young children (with his wife Natasha Parry - still his wife today) and settled comfort in England, a bit of a mess in the early 1970s, probably looked threatening to art.

His anchoring in the world of the arts, in the best senses of each word - Brook is an unrepentant internationalist, as versed in music and painting and sculpture as in drama and film - has been uncontested for decades. But it stems from factors both more practical and complex than the cultists or the naysayers dare imagine. An exceptionally restless, radical period in the 1960s, which began with his bringing Brecht to Shakespeare in a pioneering RSC King Lear in 1962, with Paul Scofield (pictured), and ended with the phantasmagorical Dream, had to be refreshed into something both less febrile and more expansive: Brook was 45, quite famous, fiercely ambitious; but he had two young children (with his wife Natasha Parry - still his wife today) and settled comfort in England, a bit of a mess in the early 1970s, probably looked threatening to art.

"England was parochial then," he's said on numerous occasions. He continues to say it - and did so again, on Nightwaves on 9 February. "It had to be parochial. There was a tradition then that was still very firm and strong, and what we call the establishment was beginning to be shaken, but the insularity really hadn't been. Paris was the melting pot."

Brook was no stranger to Paris, as he'd been going there throughout the Sixties. He knew French and the Paris theatre scene, and he wanted to be close to Parisian Jeanne de Salzmann, a disciple of the Armenian mystic G.I.Gurdjieff, whose esoteric teachings had become a kind of spiritual oxygen for the Englishman. (His rather ponderous 1979 film, Meetings with Remarkable Men, is a reconstruction of Gurdjieff's early life.)

There was, then, no simple or single reason for Brook's departure from the island, but two things remain certain. One is that he never did so as a snub to or in deprecation of England. For a man steeped in Shakespeare (whom since 1970 he has also done marvellously in French), and who owed so much of his early renown to the porous, fun, inventive ambience of the post-war and 1950s West End, the snub accusation makes no sense. The other is that Brook has never been an "exile"; as he'd be the first to suggest, this is preposterously to overdramatise.

In the 1970s, he was on the move - Asia, Africa, the Far East - hoovering up theatre idioms to add to the polycultural store he was nurturing in Paris. In the 1980s, he was creating The Mahabharata, whose English première found a generous and workable space in a former tram depot in Scotland. In the 1990s, he developed shows, in Paris, that explored the brain; and London, 16 years after the ignominious Howard-Jackson Antony and Cleopatra, welcomed the first (and only) of these to make it into English, The Man Who (at the National in 1994). Since then, he's inhabited London, not as a taxpayer but as a visiting artist, with unassuming ease. And do other thousands of Brits resident in Paris, our most desirable neighbouring European capital now reachable by the finest, fastest example of locomotive engineering in the world - which, by the way, Brook loves - ever call themselves "exiles"?

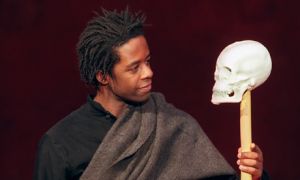

The problem with Brook is that he's never quite done what people hoped he would do. He helped found the RSC, but instead of lending the evolving ensemble his formidable talents in the 1970s, he went abroad. When he turned The Mahabharata into English, he took it not to the British capital but to Glasgow. When he did an English Hamlet in Paris, in 2000, with Adrian Lester (pictured) as the prince, he stripped the play down, cut roles and scenes, altered the order of the great soliloquies - and people were more perplexed than amazed. What, for me, was truly amazing was that exactly the same version absolutely worked, some time later, in French where it hadn't, really, in English: a typical Brook reversal of expectations.

The problem with Brook is that he's never quite done what people hoped he would do. He helped found the RSC, but instead of lending the evolving ensemble his formidable talents in the 1970s, he went abroad. When he turned The Mahabharata into English, he took it not to the British capital but to Glasgow. When he did an English Hamlet in Paris, in 2000, with Adrian Lester (pictured) as the prince, he stripped the play down, cut roles and scenes, altered the order of the great soliloquies - and people were more perplexed than amazed. What, for me, was truly amazing was that exactly the same version absolutely worked, some time later, in French where it hadn't, really, in English: a typical Brook reversal of expectations.

Now, in Eleven and Twelve, he has tackled political violence and Islamic mysticism as presented in a book by (in Britain at any rate) an unknown Malian writer, Amadou Hampaté Bâ. It's a tale about religion: though a convulsive issue in certain parts of the world, religion has hardly been fashionable in most modern Western theatre. You never know where Brook is going to find his stories or what surprises he is going to spring; and, through the decades, that's been the secret - he would never use the word - to keeping the world fascinated in him. For someone working in an art form often considered elitist and self-regarding, it's quite an achievement.

I asked him in Paris what has kept him locked into theatre.

"You’ll know perhaps, from my writing, that I’ve said continually that in the theatre we have to stage the visible, and through it, show the invisible, what’s behind it. In practice, I find when speaking about this in front of an audience, I can say, `And the...', and offer a silence and a gesture, which already speak more than the visible. Here, in Eleven and Twelve, the scenery is simple, and the playing and the words are also simple, and lead to gaps, and the gaps are what are behind the visible.

"What must have led me so long ago to choose a theme of the empty space is that that's where the perfume, the taste, the sense of something more can appear in the everyday. In every play I’ve done, all that’s interested me - and this is why I’ve never wanted to be a real `theatre director', running, say, a national theatre and feeling that I have to have a career where, at the end, I can I just tick off all the different things I’ve done - all I've wanted to do is explore by doing everything in every direction for the sake of its energy: energy and physical excitement and participating in all the different forms. Gradually, that has reduced itself into looking closely, within many, many different themes, and behind the themes, at what more could be there."

Eleven and Twelve continues at the Barbican Theatre until 27 February. Book here.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Rhinoceros, Almeida Theatre review - joyously absurd and absurdly joyful

Ionesco classic gets an entertainingly vivid and contemporary update

Rhinoceros, Almeida Theatre review - joyously absurd and absurdly joyful

Ionesco classic gets an entertainingly vivid and contemporary update

The Importance of Being Oscar, Jermyn Street Theatre review - Wilde, still burning bright

Alastair Whatley honours his subject in a quietly powerful performance

The Importance of Being Oscar, Jermyn Street Theatre review - Wilde, still burning bright

Alastair Whatley honours his subject in a quietly powerful performance

Stiletto, Charing Cross Theatre review - new musical excess

Quirky, operatic show won't please everyone, but will delight many

Stiletto, Charing Cross Theatre review - new musical excess

Quirky, operatic show won't please everyone, but will delight many

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: The Musical, Theatre Royal Bath review - not a screaming success

1950s America feels a lot like 2020s America in this portmanteau show

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: The Musical, Theatre Royal Bath review - not a screaming success

1950s America feels a lot like 2020s America in this portmanteau show

Wilko: Love and Death and Rock'n'Roll, Southwark Playhouse review - charismatic reincarnation of a rock legend

Johnson Willis captures the anarchic energy and wit of the late guitarist

Wilko: Love and Death and Rock'n'Roll, Southwark Playhouse review - charismatic reincarnation of a rock legend

Johnson Willis captures the anarchic energy and wit of the late guitarist

Dear England, National Theatre review - extra time for stirring soccer classic

James Graham adds a neat coda to his ode to decency in sport

Dear England, National Theatre review - extra time for stirring soccer classic

James Graham adds a neat coda to his ode to decency in sport

Weather Girl, Soho Theatre review - the apocalypse as surreal black comedy

A Californian weather girl copes with fires inside and outside her head

Weather Girl, Soho Theatre review - the apocalypse as surreal black comedy

A Californian weather girl copes with fires inside and outside her head

Clueless: The Musical, Trafalgar Studios review - a perfectly manicured update

KT Tunstall's new score brings bite and momentum to a high octane evening

Clueless: The Musical, Trafalgar Studios review - a perfectly manicured update

KT Tunstall's new score brings bite and momentum to a high octane evening

The Habits, Hampstead Theatre review - who knows what adventures await?

New play about the game of Dungeons & Dragons explores fact and fantasy

The Habits, Hampstead Theatre review - who knows what adventures await?

New play about the game of Dungeons & Dragons explores fact and fantasy

Farewell Mister Haffmann, Park Theatre review - French hit of confusing genre, with a real historical villain

Jean-Philippe Daguerre tries to mix a farcical comedy of manners with the Holocaust

Farewell Mister Haffmann, Park Theatre review - French hit of confusing genre, with a real historical villain

Jean-Philippe Daguerre tries to mix a farcical comedy of manners with the Holocaust

Comments

...

...