theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Antonio Pappano | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Antonio Pappano

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Antonio Pappano

On his life and loyalities divided between Rome and London

Antonio Pappano (b. 1959) enjoys the best of two opulent worlds. At the Royal Opera House in London (now his home city), he's well stuck in to his seventh season as music director, basking in popularity and plaudits previous incumbents could only have dreamt of. In Rome, he's director of the Orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, a post he took up in 2005.

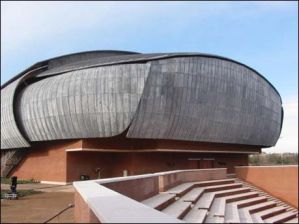

Just turned 50, Pappano is clearly comfortable in his skin, relishing artistic challenges in two European capitals. Rome is arguably entering an era of cultural renaissance, with Piano's Auditorium and Zaha Hadid's nearby Maxxi gallery for contemporary art at the heart of things. Though not Roman-born - his parents were from central-southern Italy - the marvellously unpompous Pappano is taking his place in the city's cultural history.

The symbolism is apt: the Santa Cecilia ensemble had been in abeyance for decades and, since the 1930s, effectively homeless. Now, under Pappano, they record with EMI and perform in a state-of-the-art hall, offering Romans a new focus of pride and innovation. On Sunday 10 January, Pappano rang in the new year with a premiere, Immolazione, by Hans Werner Henze. The next morning, in his spacious auditorium office, Pappano talked about his life in Rome, and about his plans both for his orchestra there and for Covent Garden. His contracts at both run until 2013.

JAMES WOODALL: How did you feel about the premiere and the entire event last night?

JAMES WOODALL: How did you feel about the premiere and the entire event last night?

ANTONIO PAPPANO: I was very happy with the atmosphere. I’ve got a sense, naturally, of being able to do this part better, and that part, and all those usual, strictly musical things are running through my head. But as a first presentation of something, it had a lot of power. That's good for new music. It didn't just sound like mathematics.

Did the orchestra take to the Henze piece kindly or did they find it quite tough?

Turning new music into something is tough work just by its very nature. Hans is also exuberant with dynamic markings, and so that the singers could be heard I had to perform some surgery. But from the very beginning, the players were taken with it - they really had to work as a chamber group; and that makes for a pretty big chamber group! They were surprised at the lyricism of it, too, and at the power of the more brutal parts.

How much new music do you try and do with the orchestra: is that an important aspect of your work together?

We do one Italian piece a year, which we commission. It was my idea to commission Hans when I found out that he'd become a friend of the orchestra, although I'd never performed any of his music. But then, when I found out he'd never been commissioned in nearly 60 years of living in Italy, I was completely taken aback. "We've got to fix this," I said. And we did.

How did your relationship with the Accademia begin? Is that a simple story or a long one?

Simple: I cancelled once, several years ago. Then, I was reinvited and there was an immediate feeling.

Why did you cancel?

I think I'd hit a wall. I was younger then and things had got too much. But as soon as I began working with Santa Cecilia, I had, as I say, this immediate feeling. I didn't know that they were - probably - looking for a music director, but I was certainly looking for some kind of symphonic entity. I'd had too much opera, so it was just about being at the right place at the right time. And then I did a new piece with them, the second performance of a piece by [German composer Peter] Ruzicka. From the start with Santa Cecilia, I had contemporary music, as well as a Ravel piano concerto, and Shostakovich. There was nothing Italian in the programming. There it was: it took off.

What are the orchestra's particular qualities?

Well, the qualities I've tried to release - because I think the orchestra had basically kind of shut down, a certain spontaneity of expression had gone.

Why do you think it had shut down?

I don't know. It's a cliché, but with an Italian orchestra you expect a certain panache, a certain colouristic sensibility. I felt, when I started with them, that they were just timid. Nothing was enough. I don't know why, really, it's not a question of blaming other conductors. It wasn't theatrical enough.

Had you been watching their work over many years?

No. I met them the first time I conducted them. But over the year or two when I was just guesting, I had the chance to do many different things with them. I grew with them. It's hard to know what's them and what's you, to be fair. I hear now, especially lately, as we're recording more, this life coming out: it's what I dream for them, where the music just jumps off the page.

Do you personally go about recruiting the members of the orchestra?

Do you personally go about recruiting the members of the orchestra?

Well, it's interesting you ask that question, because when I took over here, there were 30 places missing - 30 - so over the last two years, I've almost killed myself doing auditions. It was mainly the violins, but not only: first oboe, first bassoon, English horn we're still doing, tuba we're still doing, two bass players, we've still got three cellists we need to fill, contrabass bassoon, first viola - and so on. But this has been a fantastic thing to do, because I've been able, one, to see that there's a lot of young, terrific talent in Italy, native talent that doesn't have an outlet; and, two, to get my hands on talent that I can form and shape.

Do you also recruit from much further afield, America even?

America's more difficult, so we tend to stick to the European Union, for obvious reasons. In rehearsals, it's all very Italian, and can get loud and temperamental. I'm different here to how I am in London. For instance, I do have to say to them, "You know, with my orchestra in England, in two readings, this would have been there, just so." And then I say, "Here, we have four readings and it's because of your endless yap-yap-yap." I never do the reverse in London, I don't need to! But, on the other hand - this is essential - I've learned things about sound that I could never learn in London.

Such as?

A certain perfume; also, because of the Auditorium. Covent Garden is very dry. There's a certain type of blend here you could never achieve in London, it would be impossible. There's not the halo at the Opera House you have at English National Opera, for example, which is such a beautiful thing. But I'm very happy at Covent Garden, because I try to work on transparency, to maximise that. Here, it's different, especially with choral pieces, pieces that need an envelope: that I have here. I'm learning that music doesn't need to have corners all the time, it can do that [with his hand illustrates a wavy line]. I also try to teach these musicians, here, about flexibility, which my orchestra at Covent Garden is just unbelievable with - the listening power. That's where we've got to find here: the listening power.

And the language at work is Italian?

Absolutely. But I go into different idioms, in English, French or German or whatever, just to keep things moving. They all help me too.

How do you see the development of this orchestra in the context of the Auditorium? Is that, the building itelf, something your work is equally focussed on?

How do you see the development of this orchestra in the context of the Auditorium? Is that, the building itelf, something your work is equally focussed on?

The fact that they have a new home has helped things enormously. At the beginning, it was quite difficult because the wood - as much of it as there is - well, wood at first doesn't breathe, it's tight. So I had enormous problems making sure the violins came through. They had to play for their lives, they really, really had to play. Now, the wood is starting to breathe and we can concentrate more on a realistic dynamic balance, but it's still work in progress. I also work with the panels in the ceiling. I shift them around a great deal to try and maximise the string sound. It's still not enough, but we're getting there. Part of it is about the hall as a whole and part of it is really about the Italian tradition of not sustaining. That in fact has been my main work: sustaining the tone.

What is the Italian tradition?

It's virtuosic, close to the French manner. There is no real Italian violin school but it's a more virtuosic thing, Paganini-style, and so the sustaining quality is what I've been working on really a lot. They're getting better and better at that, it's coming.

How do you feel your position here affects, if it does, the cultural life of Rome?

People like to come to the Parco della Musica. There's a wonderful bookstore right next door. The building is in some ways unfriendly because of the distances you have to walk, but in other ways it's fascinating for its construction. The public has become very loyal: loyal to me. They've taken me to their hearts and that's been very, very important for the orchestra. The players have a point of reference, a point of focus. Now, the combination of that together, the building and the orchestra playing in it, improving and playing to a different level, and the fact that we're making records for big labels... it all plays a part. [Riccardo] Muti will come to the Rome Opera as music director, but he won't conduct more than two titles and a few concerts a year. Naturally, his is a big name and that's going to help culture overall - but the Rome Opera is in dire straits, it needs really major help. It has one of the greatest acoustics in the world but administratively it's been really difficult. But with Muti here and me here...

For the general outsider or visitor to Rome, who might be interested in culture but not au fait with the local developments in the arts scene, how would you define the impact of the Parco and the revived Accademia orchestra?

First port of call for people who come to Rome will be the Vatican, the museums and the monuments, no question. So I think we can be better at getting our message out. It is an orchestra: we're not standing on our heads. We're playing serious music. I think the building, as architecture, is fascinating. The hall is warm, with the wood and the red colouring, and if there's a quality product on top of that, that's got to be right. That's why the bookstore is important: it's part of an entire experience. For the outsider, it's not just about the music, it's many things combined. There's an incredibly varied programme: lectures, not only on music, but on mathematics, science, sociology. There are pop-music concerts, a fantastic jazz series, world music, youth events. So, with our outfit and that wide-ranging cultural brief, there's a lot to choose from.

What, as a non-Roman yourself, is your feeling about the city?

My parents were from further south, a place called Castelfranco in Miscano, a little farmland village in the Campania region, about an hour and a half inland from Naples. Rome is considered sort of south-ish, so I have a very strong connection with that element. Castelfranco the most stunning place, it's the "unTuscany". In summer, it's brown and burnt, and full of yellows, just fantastically beautiful. I go and do a concert there every summer, in memory of my father, and I try to mention the village in interviews because it needs the recognition. However small it is, it's where I'm from, it's where my parents are from, and when I'm there I see the character traits and the work ethic, where that came from, and it's amazing to recognise these things in other people. Sometimes I take a group of people from here, sometimes from Covent Garden; sometimes I mix them. We do it in a church and it's been going for five years, and I have every intention of keeping it going each year.

As for having time off: it comes in dribs and drabs. I try to get four weeks in summer. But I'm trying to be a little bit more cautious about my schedule, because I want to have a life. That's the hardest thing. If I get that, that'll be my biggest achievement! My wife [voice coach Pamela Bullock] and I have a little place in Umbria, and I love being there, it's right on a lake and I don't get there enough. I'm transformed when I come away from there, I know I am. It's become crucial. I love music more than anything, but there is, somehow, more to life.

Being here, and being Italian, can of course translate into chaos and that clichéd thing again, but there's a strong emotion in Rome certainly towards music and towards culture in general, which for me is very important. People often come up to me after a concert and say, "We experienced an emotion tonight." That for me is the measuring stick, because for them it is too. That's all in the Italian character, which becomes a glorious exchange between the orchestra, myself and the public. Rome has also helped me open up and find out things about myself I didn't know... I said before I'm quite different in front of Santa Cecilia. I occasionally go into tirades, as discipline can be difficult to impose: the yapping. There can be a chronic lack of concentration. It's something we can be better at. We can be better professionals. The players are learning to love the music, particularly the younger ones. We've played so much fantastic repertoire, so here are these kids who are just in heaven. But sometimes I have to put my foot down in a way I'd never do in London.

So how mentally, artistically, do you divide your time between the two jobs? I suspect you're doing all sorts of other things as well.

So how mentally, artistically, do you divide your time between the two jobs? I suspect you're doing all sorts of other things as well.

I am. The fact is I'm very seduced now by the symphonic thing, because it's more a looking-in-the-mirror kind of thing, to see where I really am. By its very nature, it's just me, the musicians, and the music. So I need this, to grow. Back in London, the opera world is, for me, with the orchestra, exploration of the repertoire: of what they've not played before. That's why we have things like [Shostakovich's] Lady Macbeth, [Prokofiev's] The Gambler, [Harrison Birwistle's] The Minotaur, [Korngold's] Die tote Stadt, [Tchaikovsky's] The Tsarina's Slippers and all these pieces that are new there. It's about the expansion of the opera repertoire and about deepening my relationship with my musicians, so we can achieve things in terms of colour, despite not having the help of the acoustic, but achieving, anyway, what we need to achieve. That's challenge enough, I tell you.

In Rome, what personally are you bringing to the repertoire? You must have your own taste for things the orchestra hasn't touched.

You could probably answer that question as well as I could. I come from a theatre background. Here, I don't have the trappings of the theatre. In the last five years, I've been able to enrich my experience of the music itself without those theatre trappings. But I still bring in all the theatricality and all the necessity of why music has to transmit something. For me music is nothing other than soundwaves transmitting something bigger than what the notes are. The Santa Cecilia players understand that. We have the same approach to rubato, the same approach to a singing line. That is a very, very comfortable feeling for a conductor. I don't always have to tell them how to shape this or that line, they understand instinctively.

Again, it's an Italian thing. It has to do with the language. The Italian language is horizontal, it's rarely vertical - very much like the Russian language, it's very vocal in that way. Therefore, there's an immediate point of departure. Of course, I myself sometimes have to work against that impulse, just to stay still, to be still, that's difficult. That's what we all find difficult. But it's interesting to have the same tendencies. Then, through knowledge, and through study of the score as a conductor, you somehow... With a little less of that, a little more of that - because everyone's got tendencies and what I want to do is not apologise for our tendencies, but to know when to bring them to the fore - you learn when to soft-pedal certain things. That's the real job.

Do you find yourself doing things in Rome you wouldn't do anywhere else in the world, aside from music? Do you relax in the city?

Well, I do, mainly over the dinner table, and it mainly has to do with food. I love the food, it's just outrageous - if you know where you're going. The sponsors the orchestra has here are of a generosity you can't imagine; not only in that they give money to the Accademia, but how many times have I gone to these people's houses and sat over a plate of spaghetti, nothing fancy sometimes, pasta and beans, polenta, and just feel the warmth of the family? Sure, they admire me as a musician, but I tell you my admiration for them as human beings is, like, [puts his hand on his chest] here. It's not only one couple, or one family, but several. This happens also with orchestra members but it's mainly with sponsors. You might think of them merely as "the wealthy", but they're the nicest, the most down-to-earth, the most wonderful human beings, and that has been a very rich experience.

Are you clear about what plans you can put in place for the Santa Cecilia orchestra and how to fulfil them?

Yeah, but it's a little slower here. It's both easier and harder. You can create an orchestral programme in five minutes, but to make it interesting and to pick the right people, that's harder. But I have a great team. They're all dogs with bones and always present very strong arguments. Sometimes I slap 'em down, and sometimes I say, "That's fine." Touring's vital, too. It's expanded tremendously. The orchestra's always thrilled to be on tour. Just recently we were in the Vienna Musikverein for two evenings, then in Frankfurt; we've been to Moscow, Japan - and in 2007 we were at the Proms. This international exposure has really pushed the orchestra to produce something much bigger than what they are, and that's been fascinating. The orchestra had been asleep for many years, which was a great shame, but now, together, we're really doing something.

And back in London, what are your plans?

My ideas for expanding Covent Garden's repertoire have been key. So I'll look at anything that fits in with my plans, and things like Lady Macbeth were very much part of that. I was surprised it hadn't been done before, though it kind of had, in a later version - Katerina Izmailova - but not the true one. It's been essential for me to fill in the gaps in the House's repertoire, creatively, which is where The Minotaur, for example, came from. Other things have been neglected at the House, such as Puccini's Il Trittico, very rarely done in all three of its parts. This would be a very important theatrical event, and I plan to do it.

Another is Berlioz's The Trojans, something else that Covent Garden has ignored, perhaps understandably, because it's huge. So we're initiating a production which will happen in 2012 and I'll then do it at La Scala in 2014, and it'll also be at the Vienna State Opera. For this, it's vital to have David McVicar direct, as I so admire his complete grasp of classical style, his energy with choral scenes, key as you might imagine for The Trojans. He's terrific. And I love Berlioz: I've done The Damnation of Faust several times, and I know from experience that doing Berlioz is always a marathon. This is really important for the House. I want to draw on every possible component there.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Simon Boccanegra, Opera North review - ‘dramatic staging’ proves its worth

Verdi’s political tragedy - and plea for peace - has impact in a grand Yorkshire setting

Simon Boccanegra, Opera North review - ‘dramatic staging’ proves its worth

Verdi’s political tragedy - and plea for peace - has impact in a grand Yorkshire setting

Peter Grimes, Welsh National Opera review - febrile energy and rage

In every sense a tour de force

Peter Grimes, Welsh National Opera review - febrile energy and rage

In every sense a tour de force

Owen Wingrave, RNCM, Manchester review - battle of a pacifist

Orpha Phelan brings on the big guns for Britten’s charge against war

Owen Wingrave, RNCM, Manchester review - battle of a pacifist

Orpha Phelan brings on the big guns for Britten’s charge against war

Tales of Apollo and Hercules, London Handel Festival review - compelling elements, but a failed experiment

Conceptually the two cantatas just don't work together

Tales of Apollo and Hercules, London Handel Festival review - compelling elements, but a failed experiment

Conceptually the two cantatas just don't work together

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

La finta giardiniera, The Mozartists, Cadogan Hall review - blooms in the wild garden

Mozart's rambling early opera can still smell sweet

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Der fliegende Holländer, Irish National Opera review - sailing to nowhere

Plenty of strong singing and playing, but the staging is static or inept

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Die Zauberflöte, Royal Academy of Music review - first-rate youth makes for a moving experience

The production takes time to match Mozart's depths, but gets there halfway through

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Mansfield Park, Guildhall School review - fun when frothy, chugging in romantic entanglements

Jonathan Dove’s strip-cartoon Jane Austen works well as a showcase for students

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Uprising, Glyndebourne review - didactic community opera superbly performed

Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis go for the obvious, but this is still a rewarding project

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

Fledermaus, Irish National Opera review - sex, please, we're Viennese/American/Russian/Irish

Vivacious company makes the party buzz, does what it can around it

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

The Capulets and the Montagues, English Touring Opera review - the wise guys are singing like canaries

There's a bel canto feast when Bellini joins the Mob

Add comment