Strange Beauty: Masters of the German Renaissance finds the National Gallery in curiously reflective mood. Taking as its subject the gallery’s own mixed bag of German Renaissance paintings, the exhibition sets about explaining – and excusing – the inadequacies of its collection, suggesting that it simply reflects the disdain with which German painting was once regarded. Certainly, in 1824, when the gallery was founded, the collection mainly comprised Italian and Netherlandish art, and the only German artists admitted were those who could imitate the jolly rustic scenes of Adriaen van Ostade, or the Italian-influenced landscapes of Aelbert Cuyp.

Hans Baldung Grien’s The Trinity and Mystic Pietà, 1512 (pictured right), illustrates very well the aspects of German painting so unpalatable to British viewers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The composition is astonishingly immediate: the edge of Christ’s tomb dominates the foreground, and the grief-stricken figures supporting his lifeless body are disturbingly naturalistic. For an audience primed to consider Raphael’s achievements as the pinnacle of artistic endeavour and so the standard by which all art must be judged, this painting must have been viewed as the very antithesis of Raphael.

Hans Baldung Grien’s The Trinity and Mystic Pietà, 1512 (pictured right), illustrates very well the aspects of German painting so unpalatable to British viewers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The composition is astonishingly immediate: the edge of Christ’s tomb dominates the foreground, and the grief-stricken figures supporting his lifeless body are disturbingly naturalistic. For an audience primed to consider Raphael’s achievements as the pinnacle of artistic endeavour and so the standard by which all art must be judged, this painting must have been viewed as the very antithesis of Raphael.

Far from the sort of devotional image associated with Italian Renaissance painting, peopled by idealised, remote figures, this is first and foremost a scene of a family in mourning, God the Father depicted as a wizened old man, the Virgin’s eyes pink from crying. The painting is brutally frank, a gripping piece of emotional drama involving people not so dissimilar to its viewers, while the tiny kneeling figures of the artist’s patron and his family employ a drastic change in scale that to pre-Modernist, nineteenth-century eyes, must have jarred with fundamental ideas about the conventions and purposes of picture-making.

By highlighting differences in the reception of German and Italian painting, the exhibition steers us towards an interpretation of the gallery’s patchy collection of German art as merely idiosyncratic, a historical byway that reflects the ways in which tastes, values and perceptions of beauty have changed over time. This agenda is pushed forcibly throughout, with the final room containing no paintings, its walls covered instead with such pseudo-philosophical questions as, "Is ugliness more authentic than beauty?", and "How should we judge art of the past?" In some ways the National Gallery seems to have fallen into a trap of its own making, because in its specific scrutiny of its own collection, the exhibition reveals, apparently inadvertently, a raft of historic blunders and misjudgements that are inevitably, if unfairly, far more interesting than generalised ponderings about the nature of art.

The nub of the show is found in the sorry remains of the Liesborn Altarpiece, probably 1470-80 (see main picture), the fragments of which were bought by the National Gallery in 1854 by order of the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Gladstone, who seems to have been far more enlightened about the merits of German painting than anyone at the National Gallery. The purchase of the altarpiece caused such public outrage that an Act of Parliament forced its swift resale, an action so extraordinary that it has never been repeated before or since.

But the glaring scandal that passes without comment here is that rather than simply selling the panels as parts of a whole, the gallery cherry-picked and retained the panels it felt to be of most value, before selling the rest. Consequently, all that is on offer here is the depressing sight of the National Gallery’s eight panels, while those in the possession of other museums are reproduced in miserable monochrome as a sort of visual mea culpa, as if the Gallery cannot quite believe its own folly.

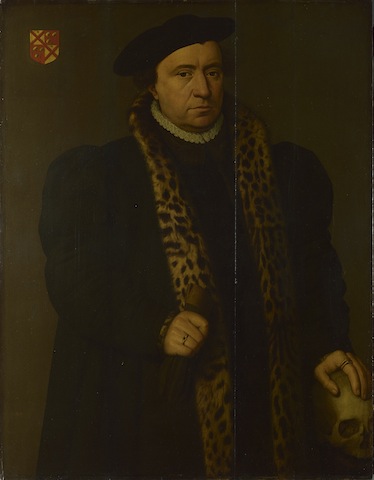

Two rooms pointlessly dedicated to the defining characteristics of German Renaissance art appear to be a hastily conceived attempt to deflect attention from the National Gallery itself, which is, nevertheless, subject to yet further embarrassment in a room dedicated to Cranach, Holbein and Dürer. The gallery actively acquired works by these artists, but its lack of expertise in German painting meant that a number of acquisitions have turned out to be by someone else entirely, with one such painting, A Man with a Skull, c1560 (pictured left), thought to be a Holbein, causing uproar when it turned out to be by someone called Michiel Coxcie. That it is nevertheless a fine painting and of interest in its own right seems not to have mattered, and the gallery's Keeper was forced to resign.

Two rooms pointlessly dedicated to the defining characteristics of German Renaissance art appear to be a hastily conceived attempt to deflect attention from the National Gallery itself, which is, nevertheless, subject to yet further embarrassment in a room dedicated to Cranach, Holbein and Dürer. The gallery actively acquired works by these artists, but its lack of expertise in German painting meant that a number of acquisitions have turned out to be by someone else entirely, with one such painting, A Man with a Skull, c1560 (pictured left), thought to be a Holbein, causing uproar when it turned out to be by someone called Michiel Coxcie. That it is nevertheless a fine painting and of interest in its own right seems not to have mattered, and the gallery's Keeper was forced to resign.

This episode, along with the other examples of misattribution in this room, makes plain our collective obsession with a canon of celebrity artists, and however much this exhibition might leave us appalled by the whims and fancies of long-dead directors of the National Gallery, it reminds us too that some things, however foolish, will never change, amongst them the unassailable cult of "authenticity".

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment