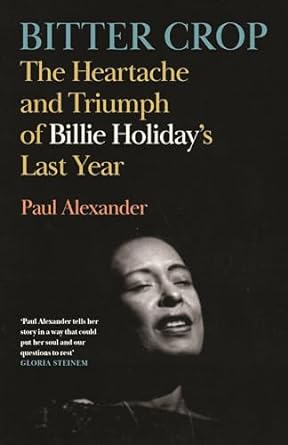

Paul Alexander: Bitter Crop - The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday's Last Year review - setting the record straight | reviews, news & interviews

Paul Alexander: Bitter Crop - The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday's Last Year review - setting the record straight

Paul Alexander: Bitter Crop - The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday's Last Year review - setting the record straight

Busting myths in this sensitive appraisal of a jazz legend

It’s often said that nobody mythologised Billie Holiday like Billie Holiday. I’m not so sure.

In this fine, clear-eyed biography, Paul Alexander documents Holiday’s propensity for feeding the media inaccuracies and tall tales, her enthusiastic embrace of “the adage that said the truth should never stand in the way of a good story.” But the media gave as good as they got, downplaying her artistic achievements and fixating on her problems with substance abuse and exploitative, violently toxic male partners.

Many of the myths imposed upon her during her lifetime persist, particularly those that linger around her early death. It’s worth ticking a few off here, for the record. Holiday was not a tragic figure. She didn’t die a junkie, or a has-been. The three main eras of her career – at Columbia, Commodore/Decca, and then Norman Granz’s Verve – don’t plot a steady decline in her abilities. She was never, despite the innumerable times and contexts in which the label was lazily applied, a ‘blues singer’. And it’s a facile misconception to regard her art as doleful or depressing, a mournful expression of her supposedly pitiful, unhappy life.

Refreshingly, the main thrust of Alexander’s book is to assert that despite the heartaches and vicissitudes she endured, Billie Holiday rightly regarded her life as a triumph. The opening chapter, "Last Night at The Flamingo Lounge", a vivid account of Holiday’s final nightclub appearance, highlights the singer’s determination to “do whatever it took to carry on.” It could stand as a metaphor for her whole life. The press loved portraying Holiday as a victim, but she didn’t see it that way. Alexander quotes her friend (and ghostwriter of her autobiography) William Dufty: “What she really felt, the Rosebud to understanding her, was that her life was a triumph.” Having survived what Alexander understatedly describes as “hardscrabble beginnings”, she had become “a living legend”, her life “a beautiful success.”

Refreshingly, the main thrust of Alexander’s book is to assert that despite the heartaches and vicissitudes she endured, Billie Holiday rightly regarded her life as a triumph. The opening chapter, "Last Night at The Flamingo Lounge", a vivid account of Holiday’s final nightclub appearance, highlights the singer’s determination to “do whatever it took to carry on.” It could stand as a metaphor for her whole life. The press loved portraying Holiday as a victim, but she didn’t see it that way. Alexander quotes her friend (and ghostwriter of her autobiography) William Dufty: “What she really felt, the Rosebud to understanding her, was that her life was a triumph.” Having survived what Alexander understatedly describes as “hardscrabble beginnings”, she had become “a living legend”, her life “a beautiful success.”

This isn’t the first Holiday book to focus on art instead of scurrilous myths. John Szwed’s 2016 biography, Billie Holiday: The Musician and The Myth, made its purpose clear from its subtitle onwards. Credit too to Robert O’Meally’s The Many Faces of Billie Holiday, which, like Szwed’s book, melded biographical fragments with lucid, insightful descriptions of Holiday’s songs and, in particular, the power, complexity, and uniqueness of her voice.

It’s an odd, almost otherworldly voice. Alexander notes that “for years critics and jazz lovers had tried to describe its eccentricity.” O’Meally annotated the dualities of its timbre: “now wine-dark, now scalpel-bright.” At times, Holiday’s voice splashed joyful surprise across the listener’s consciousness like clusters of raindrops in a sudden sunshower; other times, it invoked an ineffable paradox of pleasure and pain: her voice sounded like nostalgia feels.

All of these aspects endured, and deepened, as she aged. Yet many recoiled in horror at her later vocals, ignoring the fact that what her voice may have lost in youthful buoyancy, was more than compensated for by a richer, more lived-in tone and complexity, blooming into what ‘Jazz Scene’ columnist John McLellan called “a ripe, mature beauty.”

Lady in Satin, her penultimate album, is probably still her most divisive. Alexander considers it “a masterpiece”, and devotes a fascinating chapter to its genesis and recording, but the idea that it marked a final milestone in Holiday’s “sad decline” has now crystalised into cant. This blinkered view ignores the fact that artists change. If not, they risk becoming, in the words of saxophonist Lester Young – Holiday’s key musical collaborator, platonic soulmate, and originator of her ‘Lady Day’ sobriquet – “a repeater pencil”.

Any Holiday biography is necessarily also a chronicle of the times she lived in, an era awash in vicious racism. As for "Strange Fruit" – the incendiary anti-lynching song which provides this book with its title – Holiday’s “close association with the song drew the ire of Harry Anslinger, the director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics,” who “launched a vendetta against her”. Holiday was vulnerable due to her well documented history of intermittent heroin addiction, and the state homed in on that weakness like a drone strike. This resulted in “a drug bust in 1947 that landed her in prison in Alderson, West Virginia, for a year-and-a-day sentence.”

Holiday was framed for heroin possession on her deathbed, and arrested. The NYPD, in an act of petty vindictiveness, subjected her to fingerprinting and a mugshot, and confiscated her record player, radio, magazines, and flowers. Before “this ordeal”, writes Alexander, “Billie had been improving”. After this “sinister – and intentional – tactic of intimidation”, it was not long before “her physical and emotional well-being began to deteriorate.”

If there was a tragedy to Billie Holiday’s life, it lay in the fact that the State hounded, harassed, and, in the end, killed her. “The motherfuckers really were out to get her”, jazz singer Annie Ross says. “Lady felt she was a target of the government because of the nature of the arrests and how they were carried out. She felt there was a plot to destroy her. She was right.”

Once Holiday was dead, the media continued to twist the knife. Her obituary in Time – “Negro blues singer”; “schooled in a Baltimore brothel”; “stubbornly nursed her resentment”; “succumbed to dope addiction” – was, Alexander says, “not a recapitulation of what Billie achieved in her life and career but an effort by the establishment to marginalize her as an artist and deride her as a woman, all with a not-so-subtle undertone of racial animus.”

For Sonny Rollins, “Billie was a consummate artist. She was at least a genius.” She was an artist determined to “do whatever it took to carry on”. Her art will last as long as there are people left to enjoy art. As Nat Hentoff put it, “Other singers sing about emotion, Billie actually projects the emotion itself.” Dropping the needle on a Billie Holiday record offers access to the closest thing to a secular miracle any of us are ever likely to encounter. Paul Alexander has made a significant contribution to rescuing the artist from the myths. This is an important book. It is, in its own quiet way, a triumph.

- Bitter Crop: The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday’s Last Year by Paul Alexander (Canongate, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment