Clare Carlisle: Philosopher of the Heart review – how to be human | reviews, news & interviews

Clare Carlisle: Philosopher of the Heart review – how to be human

Clare Carlisle: Philosopher of the Heart review – how to be human

Great Dane unleashed: an immersive portrait of Kierkegaard

How close should a biographer come to her subject? Clare Carlisle stays by the side, and looks through the eyes, of Søren Kierkegaard at almost every step on his maverick journey. Philosopher of the Heart even closes with a glimpse of Carlisle in tears at a bicentenary celebration for Kierkegaard at the Danish Church in London.

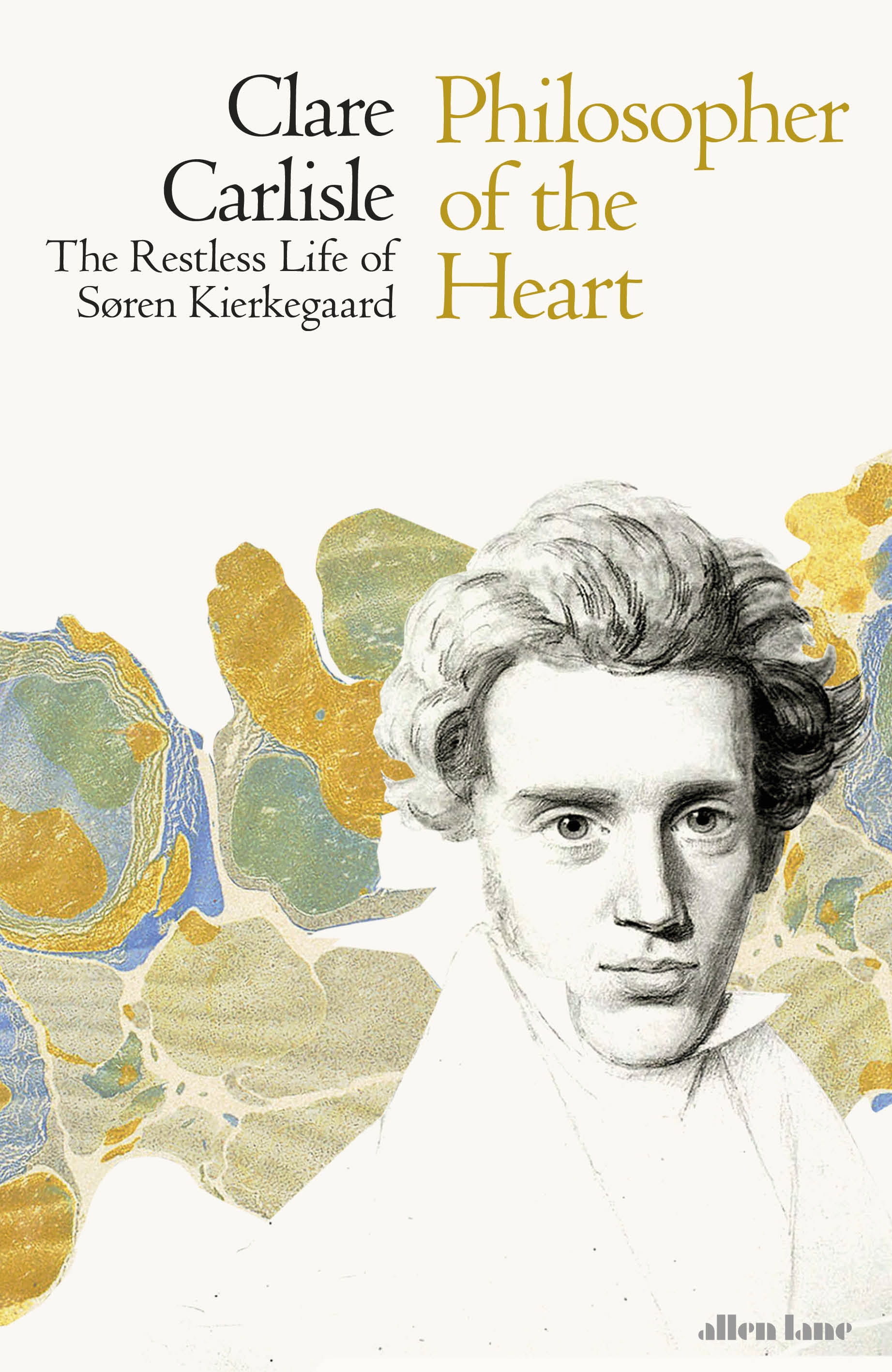

It’s a very Kierkegaardian moment, one of several in her book: unashamedly subjective, lyrical, impassioned and impatient with the buttoned-up, life-denying formality of conventional philosophy – conventional biography too, for that matter. Those qualities make her study of this ironic, ecstatic and anguished outsider a deep pleasure, but a challenge as well, for the curious lay reader. They also explain why anybody who seeks above all a straightforward, hand-holding introduction to the great Dane often labelled the “father of existentialism” should probably apply elsewhere. Carlisle has crafted a Kierkegaard-style portrait of an author who disdained the abstract philosophy of systems, doctrines and propositions in favour of writings that tried to capture “the compelling drama of being human that unfolds within every person”. Truth, for him, must be experienced without filters “in the middle of life itself”, not theorised from a safe distance. Carlisle knows, perhaps too well, that to reduce this pioneering mission – yes, an “existential” quest if you like – to a list of bullet-point axioms would be to betray the essence of his work. At the same time, at moments I did feel glad that more boringly didactic expositors, such as the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (at plato.stanford.edu/), have gone in for such helpful treachery.

With that proviso, Philosopher of the Heart enacts Kierkegaard’s audacity and verve in thinking and writing, his “new way of doing philosophy”, in a thrillingly inward and intimate style. Carlisle (pictured below) avoids any blow-by-blow, concept-by-concept elucidation of events and ideas. Rather, she offers a series of immersive and impressionistic scenes, closely woven with lavish quotation from her primary sources. Much of her narrative pivots around a few key episodes in the fairly brief life (1813-1855) of this son of a pious, self-made Copenhagen merchant and a beloved mother who also came from the humblest peasant stock. Young Kierkegaard, indeed, only stood two generations away from serfdom.

After drawn-out student years, he graduated in theology but spurned the expected church career. He spent his inherited wealth to support an existence as a freelance author in Copenhagen, labouring to make his name via literary work “through the sheer force of its argument and style”. After Kierkegaard broke off his engagement with his fiancée Regine Olsen in 1841, a rupture that later shaped both life and thought, he stood alone and exposed. This tormented oddball performed his prophetic fury under the often-mocking gaze of his gossipy town, a brave but ludicrous figure “burdened with this absurd ego slumped like a fragile giant upon his shoulders”. Shattered, Regine justifiably thought that Søren had played a “terrible game” with a vulnerable young woman. Yet her errant suitor remained obsessed with Regine, never ceased to crave her approval, and finally appointed her his heir. He had rejected bourgeois marriage just as he spurned the bourgeois Christianity of the Danish Lutheran church. Instead, he embarked on his restless, zigzagging hunt for a “completely human life” free of institutional repression and the false dogmas peddled by preachers and philosophers: “A man must first learn to know himself before knowing anything else”.

After drawn-out student years, he graduated in theology but spurned the expected church career. He spent his inherited wealth to support an existence as a freelance author in Copenhagen, labouring to make his name via literary work “through the sheer force of its argument and style”. After Kierkegaard broke off his engagement with his fiancée Regine Olsen in 1841, a rupture that later shaped both life and thought, he stood alone and exposed. This tormented oddball performed his prophetic fury under the often-mocking gaze of his gossipy town, a brave but ludicrous figure “burdened with this absurd ego slumped like a fragile giant upon his shoulders”. Shattered, Regine justifiably thought that Søren had played a “terrible game” with a vulnerable young woman. Yet her errant suitor remained obsessed with Regine, never ceased to crave her approval, and finally appointed her his heir. He had rejected bourgeois marriage just as he spurned the bourgeois Christianity of the Danish Lutheran church. Instead, he embarked on his restless, zigzagging hunt for a “completely human life” free of institutional repression and the false dogmas peddled by preachers and philosophers: “A man must first learn to know himself before knowing anything else”.

Paradoxically, Kierkegaard practised this prototype of modern rebellion in the public eye on the smart streets of Copenhagen, fed by his fast-dwindling investments and bound into the city’s professional networks. He delivered sermons in churches, haunted newspaper offices and cafés, cultivated (and quarrelled with) editors, professors and clergymen. Kierkegaard hustled, often effectively, in this busy cultural marketplace among rivals who also “earned their living from their ideas, their imaginations, their skilled use of language”. Carlisle sketches the social and intellectual backdrop to his dozen years of intensive “authorship” with flair and insight, from the theme-park novelties of the new Tivoli Gardens to the spats and rumours of the scurrilous press, even the foul stench of the tanneries on the street where he lived. She reminds us that his milieu overlapped with that of Hans Christian Andersen (to whom he once gave a lousy review): both of them shape-shifting literary experimenters and entrepreneurs, trying to do original things with old but re-purposed forms.

The 1840s saw the torrential production of one major work after another – Either/Or; Fear and Trembling; Repetition; The Concept of Anxiety; Works of Love; The Sickness Unto Death – in a flood of creativity that has precious few counterparts in the history of philosophy, or literature. Kierkegaard pushed philosophy off its shiny new academic tracks, as followed by the system-building Hegelians he despised, into the richer literary territory of the dialogue, the diary, the parable, the soliloquy, the sermon. They transformed his “innate tendency to hyper-reflection” into a vision of struggling selfhood in a lonely and anxious age. It has infused the work of his admirers and disciples from Kafka to Auden; from Wittgenstein to Sartre. His modes of thinking, of feeling, remain ours; not least in his exploration of anxiety, that florid symptom of freedom that he sees as “a blessing as well as a curse”, since “whoever has learned to be anxious in the right way has learned the ultimate”. His still-radical ideas play out in a theatre of the mind peopled with a vividly eccentric cast. A variety of pseudonymous characters, from “Victor Eremita” and “Johannes the Seducer” to “Judge William”, signed his works. “None of these men are Søren Kierkegaard,” Carlisle clarifies: “they are paths which converge at the question of his own existence.”

His radically individualist version of the Christian faith repudiated not only the cosy rituals of the Lutheran hierarchy in Denmark but also – as Fear and Trembling shows in its mightily influential meditation on Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac – the austerity of righteous self-denial. For Kierkegaard, “the divine inhabits the finite”, and “perhaps the soul does not lose itself in the world, but finds itself there”. Strolling among, socialising with, Copenhagen’s artistic and ecclesiastical elite, he would find himself forever caught “in a dialectic between worldly achievement and ascetic renunciation”. For him, the “knights of resignation” may shun everyday concerns; but true “knights of faith” return to them. Yet he always sought to reclaim the shock and threat of Jesus’s life and teaching from the “comfortable worldliness” of middle-class piety embodied in his lifelong bugbear: the unctuous Bishop Mynster. From first to last, theological debate powers Kierkegaard’s prose. Carlisle correctly refuses to downplay its role. His communion homilies, collected as Upbuilding Discourses, aim to rescue the “divine scandal” of original Christianity, with its “dangerous and uncertain path”, from the Establishment that fraudulently claimed authority in its name. If most of her readers will not identify with organised religion, no matter: Kierkegaard himself detested its smugness and hypocrisy more vehemently than any atheist. As she writes, “He spoke of, and to, a deep need for God within the human heart – a need for love, for wisdom, for peace – and he did so with a rare and passionate urgency”. Her book powerfully shares that passion, and that urgency.

His radically individualist version of the Christian faith repudiated not only the cosy rituals of the Lutheran hierarchy in Denmark but also – as Fear and Trembling shows in its mightily influential meditation on Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac – the austerity of righteous self-denial. For Kierkegaard, “the divine inhabits the finite”, and “perhaps the soul does not lose itself in the world, but finds itself there”. Strolling among, socialising with, Copenhagen’s artistic and ecclesiastical elite, he would find himself forever caught “in a dialectic between worldly achievement and ascetic renunciation”. For him, the “knights of resignation” may shun everyday concerns; but true “knights of faith” return to them. Yet he always sought to reclaim the shock and threat of Jesus’s life and teaching from the “comfortable worldliness” of middle-class piety embodied in his lifelong bugbear: the unctuous Bishop Mynster. From first to last, theological debate powers Kierkegaard’s prose. Carlisle correctly refuses to downplay its role. His communion homilies, collected as Upbuilding Discourses, aim to rescue the “divine scandal” of original Christianity, with its “dangerous and uncertain path”, from the Establishment that fraudulently claimed authority in its name. If most of her readers will not identify with organised religion, no matter: Kierkegaard himself detested its smugness and hypocrisy more vehemently than any atheist. As she writes, “He spoke of, and to, a deep need for God within the human heart – a need for love, for wisdom, for peace – and he did so with a rare and passionate urgency”. Her book powerfully shares that passion, and that urgency.

- Philosopher of the Heart: the Restless Life of Søren Kierkegaard by Clare Carlisle (Allen Lane, £25)

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment