Jenny Diski: Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? Essays review - a posthumous collection from the pages of the LRB | reviews, news & interviews

Jenny Diski: Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? Essays review - a posthumous collection from the pages of the LRB

Jenny Diski: Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? Essays review - a posthumous collection from the pages of the LRB

Bright white luminescence from an elegant and thought-provoking writer

“Jenny Diski lies here. But tells the truth over there.” That was Diski’s response to daughter’s Choe’s observation that if she were buried – a friend had just offered her a spot in a plot she’d bought amid the grandeur of Highgate Cemetery – she’d need a headstone. Cremation and the music would have to be “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes”, Diski said.

Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? Essays brings together some thirty essays of more than 200 written for the London Review of Books from 1993 to her death in 2016. The magazine’s founding editor, Karl Miller, met Diski at a party and suggested to his deputy, the eccentric and bird-like Mary-Kay Wilmers, that she get in touch with her: “You’ll get on with her… she’s a bit like you.” And so they did, and so she was. By the time she began at the LRB, really the only outlet for long-form journalism in Britain, Diski had already written five novels. Her most celebrated work, the memoir-cum-travelogue Skating to Antarctica, would appear in 1997.

The terrain it covered – a childhood which redefined the meaning of “dysfunction” and led to suicide attempts and several stays in a mental hospital – is revisited in “A Feeling for Ice”, the longest essay in this book, in which her infatuation with vast expanses of borderless white nothingness, acquired in the long white ward, is discussed, from her childhood love of ice-skating to a trip to Antarctica, with its “floating mountains of blue ice shaded with white, white ice shaded blue”. Chloe had persuaded her to look into her childhood, a journey begun only reluctantly by going back to Paramount Court, on London’s Tottenham Court Road, where Diski grew up, the only child of Jewish immigrants. Her father had run off in the wake of one of her mother’s breakdowns. From old neighbours still there, she learned that the man she thought a charmer had been a professional con man who committed suicide, an event in which her mother had taken delight. Both parents had sexually abused her, which she only recognised in retrospect, and she’d grown up in foster care and later been taken in and mentored for four years by Doris Lessing, whose son she came to know at school. When she returns from a cruise to the real Antarctica, Diski finds her mother’s death certificate, obtained by Chloe, among the mail: “Only for the last eight years had she truly not existed; only since 1988 had I been orphaned, really safe.”

The finding seems to have been cathartic but, unsurprisingly, Diski never fully recovered from the loss and trauma of her childhood. Depression and madness were perennial themes of her writing which nevertheless ranged widely. Many of the essays here take flight from books, rarely reviews as such (though she does of course pass judgment) but think-pieces, which interrogate both book and author: Piers Morgan’s so-called diaries (“Politics and reality TV are one and the same at present, if the Piers Morgan experience is anything to go by” she writes presciently); Tom Bower’s uninsightful biography of Richard Branson, which leaves many dots unjoined; Tina Brown on Diana (the absurd and vulgar psychobiography of the Princess’s final moments). Howard Hughes was a brilliant weirdo, but Diski reserves her acid for Charles Higham, the notorious celebrity biographer.

The finding seems to have been cathartic but, unsurprisingly, Diski never fully recovered from the loss and trauma of her childhood. Depression and madness were perennial themes of her writing which nevertheless ranged widely. Many of the essays here take flight from books, rarely reviews as such (though she does of course pass judgment) but think-pieces, which interrogate both book and author: Piers Morgan’s so-called diaries (“Politics and reality TV are one and the same at present, if the Piers Morgan experience is anything to go by” she writes presciently); Tom Bower’s uninsightful biography of Richard Branson, which leaves many dots unjoined; Tina Brown on Diana (the absurd and vulgar psychobiography of the Princess’s final moments). Howard Hughes was a brilliant weirdo, but Diski reserves her acid for Charles Higham, the notorious celebrity biographer.

There’s a wonderful essay on the office, within which is a beguiling secondary essay on the enticements of the stationery cupboard: gentle and nostalgic. On those two bizarre killers, Jeffrey Dahmer and Dennis Nilsen, she is viscerally unsettling, trying somehow to “account” for their behaviour while wondering whether books about them are strictly necessary. Revisiting in adulthood Anne Frank’s diary offers an entirely different experience from her childhood reading, when the main point of interest was a shared dislike of mothers. In “Did Jesus Walk on Water Because He Couldn’t Swim?” and “Jews and Shoes”, the latter about “schlepping and cobbling… academic cultural studies at its most anxious”, Diski combines high erudition with high entertainment. As for “The Friendly Spider Programme”, anyone who keeps suitable weaponry on standby and shares a “paranoid theory that I summoned up spiders through the power of thought” will read it from behind a cushion.

America, the America opposed to Trump that is, cherishes and reveres essayists. The Brits, both left and right, tend to have a shorter attention span. We need more essays and Diski was a loss. Reading her now reminds me of the late great Pauline Kael in the New Yorker – or Dorothy Parker, had she been less indolent. Mrs P wanted her headstone to read “Excuse My Dust”.

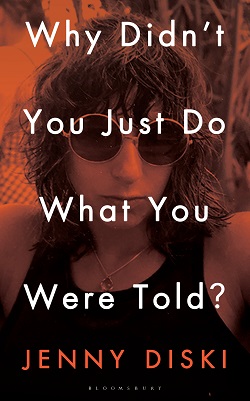

- Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? Essays by Jenny Diski (Bloomsbury, £18.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment