Writing in the Edinburgh Review in 1814, Francis Jeffrey began his review of Wordsworth’s The Excursion with a provocative denunciation of romanticism: “This will never do,” he complained. “It bears no doubt the stamp of the author’s heart and fancy; but unfortunately not half so visibly as that of his peculiar system.”

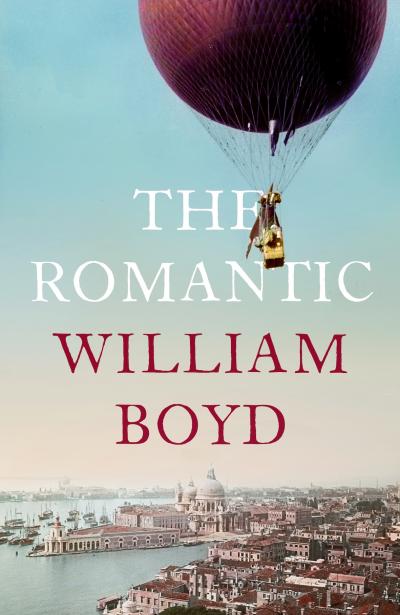

William Boyd’s latest excursion into fictional biography, aptly entitled The Romantic, is the fourth of the “whole-life” novels he has made his speciality, following The New Confessions (1987), Any Human Heart (2002) and Sweet Caress (2015). It will almost certainly do, as far as his legion of admiring readers is concerned. Yet Jeffrey’s second sentence, less well known than his first, highlights the peculiarity of Boyd’s now systematic treatment of this cradle-to-grave genre.

The bare bones of his latest story, in which Cashel Greville Ross, a “cut-price Byron substitute” – and illegitimate son of an Irish baronet – seeks a coherent life first as a soldier at Waterloo, and grand tourist in Italy, and then, more cynically, as a bestselling author in Dickensian London, a farmer in Massachusetts, a Nicaraguan diplomat and an African explorer in the guise of Sir Richard Burton, make up a tasty menu pastiching 19th-century fiction, biography, travelogue, and memoir. There is a dollop of Tolstoy, for instance, in the Waterloo scenes, which also evoke Stendhal’s depiction of the battle in The Charterhouse of Parma.

However, unlike that epic yet intimate tale of political intrigue and erotic frustration, Boyd’s novel is more of an historical soap opera than a literary masterpiece. In Pisa, in the spring of 1822, Ross inveigles himself into the dissolute circle of Byron and Shelley. Yet Boyd’s focus on Romanticism itself is perfunctory, and he is generally more interested in the poets’ famous libidos than in any literary dimension of their lives. He sleeps with Mary Shelley’s step-sister Claire Clairmont and falls in love with a teenage friend of Byron’s mistress, Teresa Guiccioli, becoming her cavalier servente (which is repeatedly misspelt). His star-crossed love affair with the beautiful (and, it must be said, rather dull) contessa, Raphaella Rezzo, bookends his sexual career but, in truth, Ross is more of a gallant than a romantic and a few torrid scenes lend the novel the mass-market feel and prose of pulp fiction: “Raphaella hauled up her blue-and-silver skirts to reveal her pale naked thighs above her gartered silk stockings and the dark ‘V’ of her pudenda.”

Headlong momentum often takes its toll on narrative coherence but there are many incidental pleasures. Even if Boyd never signals that, in the Pisan spring, Byron was actually writing Don Juan, the greatest poem to be published in English between Paradise Lost and The Prelude, there is still a moving description of Shelley’s drowning in a schooner named Don Juan, and his auto-da-fé on the beach at Viareggio is skilfully adapted from Edward John Trelawny’s Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron.

Headlong momentum often takes its toll on narrative coherence but there are many incidental pleasures. Even if Boyd never signals that, in the Pisan spring, Byron was actually writing Don Juan, the greatest poem to be published in English between Paradise Lost and The Prelude, there is still a moving description of Shelley’s drowning in a schooner named Don Juan, and his auto-da-fé on the beach at Viareggio is skilfully adapted from Edward John Trelawny’s Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron.

Trelawny himself, an East India Company veteran perambulating through Europe’s literary salons on half-pay could be the model for Boyd’s hero. So, too, could another shadow player in the Pisan drama, the Irishman John Taaffe, here mysteriously entitled “Count Taaffe”. Like Cashel Ross, Taaffe was a Dantescan expert who accompanied Byron and Shelley on the shooting party that resulted in a near fatal stabbing of an Italian cavalry officer, Sergeant Stefani Masi. Boyd makes a vignette of this otherwise uneventful expedition, giving us its exact date and location in the Pisan countryside, but surprisingly omits to mention the complicated affray, in which Shelley himself was also wounded. Here, as elsewhere in The Romantic, truth is more exotic than fiction. Or is Boyd’s glaring omission just another playful trick, his ironic disconnect?

Unfortunately Cashel Greville Ross doesn’t have the charisma of Boyd’s earlier “whole-life” heroes – or heroine, in the case of Sweet Caress. Like Amory Clay in that novel, John James Todd (in The New Confessions) and Logan Mountstuart (in Any Human Heart) were born shortly before World War One and their lives encapsulate the 20th century whose twists and ironies Boyd instinctively knows well. He is less at home in the preceding century and, as a result, The Romantic fails to achieve the same depth and focus, while often flirting with the superficial and absurd. “What’s going on in the world, Ross, do you know? I haven’t seen a newspaper in months,” a friend asks in the south of France, to which the Romantic unromantically replies: “Neither have I. In Arles, the other day, I heard that Simon Bolivar was made the President of Peru.” It must have been the talk of the town!

- The Romantic by William Boyd (Viking, £20.00)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment