CPE Bach: Complete Piano Trios Linos Piano Trio (C-Avi)

CPE Bach: Complete Piano Trios Linos Piano Trio (C-Avi)

13 piano trios squeezed onto just two discs is a steal, but we’re talking CPE Bach and not Schubert, and there’s the issue of whether these pieces are piano trios in the accepted sense. Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach’s London publisher issued the Wq 89 set in 1776, describing them as “Six Sonatas for the Harpsichord or Pianoforte accompanied by Violin and Violincello”. The composer variously referred to them as trios, sonatas or “Trios (which are also Solos)”. They were an instant success, and Bach added a further set shortly afterwards, early examples of what would become one of the most significant chamber music forms. He presumably imagined them played on a domestic square piano. The Linos Piano Trio are the first group to record the trios on modern instruments. Balance is never an issue; pianist Prach Boondiskulchok’s light, crisp playing is ideal, never swamping Konrad Elias-Trostmann and Vladimir Waltham on violin and cello. These are fabulously entertaining works. Take the opening seconds of the earliest, E minor trio, the keyboard’s prim opening gesture interrupted by a shrill string shriek, or the serene C major chords at the start of its successor. Bach’s volatility is extraordinary; he’ll toss you a smile one minute and bare his teeth just seconds later.

Take the beginning of the Wq 91 F major trio, the mellow piano intro abruptly shoved aside within just a few bars. Or the cascading flourish which opens the Wq 90 C major trio; the string parts aren’t virtuosic, but the keyboard writing would make little sense without them. Some moments should provoke laughter, as with the stuttering finale of Wq 90’s A minor work, though Bach’s melting slow movements offer relief. They tend to be incredibly compact, a favourite being the tiny “Poco andante” of Wq 91, soft, sustained string chords giving meaning to the keyboard part. This music will enrich anyone’s life. The performances are consistently excellent, with Boondiskulchok’s notes both scholarly and entertaining.

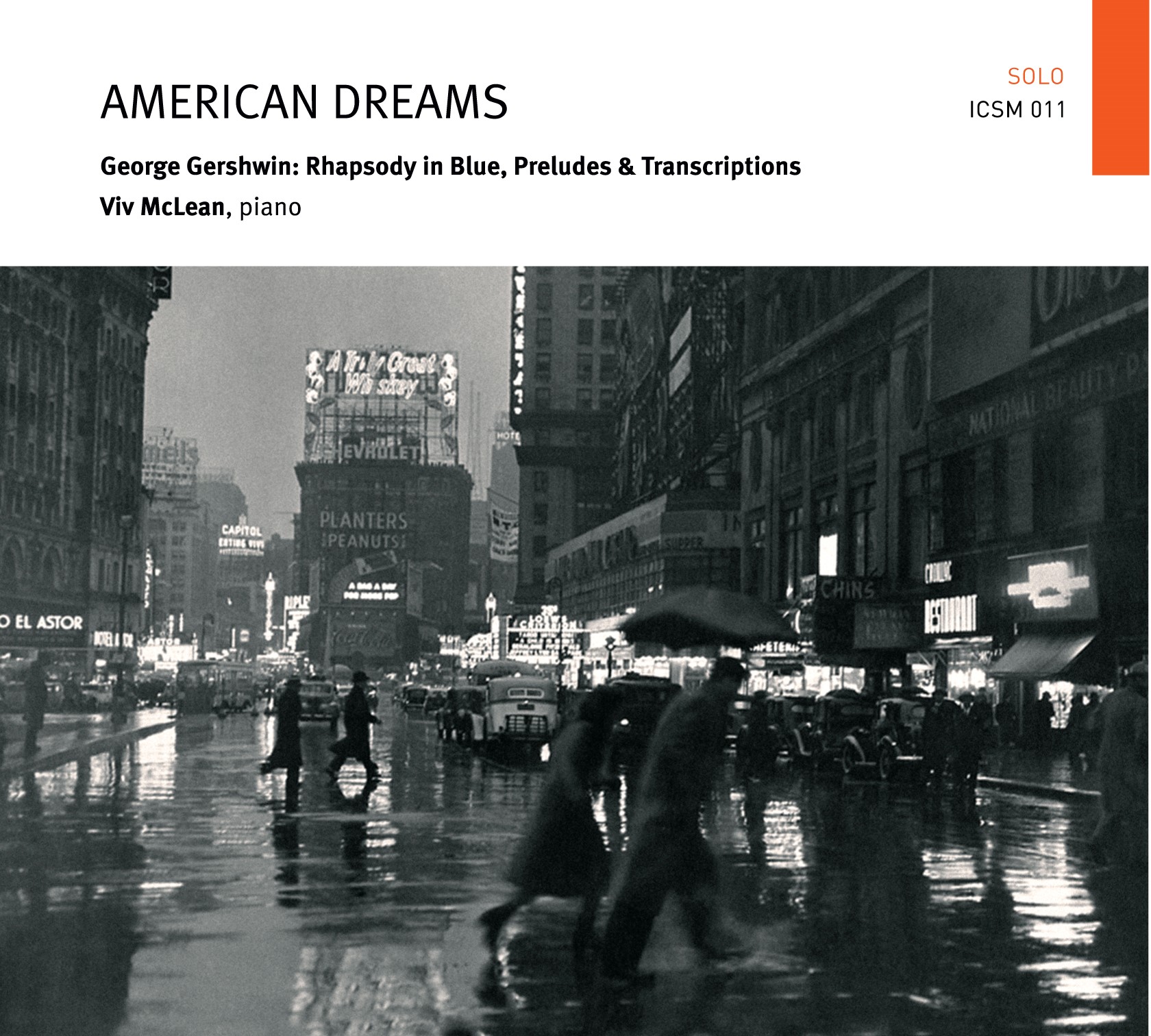

Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue, Preludes & Transcriptions Viv McLean (piano) (ICSM Records)

Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue, Preludes & Transcriptions Viv McLean (piano) (ICSM Records)

How Gershwin’s music would have developed had he not died tragically young is one of the great musical what-ifs. The breezy early songs are perfect in their own way, but the gulf between them and works like Porgy and Bess and the final film scores is huge, Gershwin’s hunger to learn and evolve pushing him to ever greater heights. Rhapsody in Blue remains his signature piece, but Bernstein wasn’t being harsh when he described it as “not a composition at all… a string of separate paragraphs stuck together. You can cut parts of it without affecting the whole.” I’m the only person I know who prefers the Second Rhapsody and Variations on I Got Rhythm, both works leagues ahead in terms of coherence. We don’t often hear Gershwin’s solo piano version of the Rhapsody. It’s fascinating, both as a virtuoso transcription and in terms of its bringing us back to the work’s improvisatory origins. The few cuts suggest that Bernstein was correct; this Rhapsody still sounds authentic. Having just one musician allows for far greater rhythmic flexibility, and pianist Viv McLean’s technical mastery is never deployed for its own sake. He makes us believe that he’s composing it on the spot, and passages like the very rhetorical lead-in to the big tune are irresistibly done.

Couplings include the Three Preludes and a generous selection of song arrangements. The bluesy second prelude is sweetly done, and the harmonic boldness of a song like “Who Cares” is striking. Percy Grainger’s take on “The Man I Love” is appealing, and there’s a nifty abridged version of An American in Paris arranged by composer Maurice Whitney. Three bonus tracks come from a 2007 McLean album; brilliantly orchestrated versions of songs for piano and orchestra made by Hershy Kay, best known for his work on Bernstein’s On The Town and Candide. They’re highly enjoyable, McLean gamely supported by Simon Lee’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. It’s all excellent, and the booklet includes Gershwin’s 1933 essay The Composer and the Machine Age.

King Frederik IX Conducts Royal Danish Orchestra & Danish National Symphony Orchestra (DaCapo)

King Frederik IX Conducts Royal Danish Orchestra & Danish National Symphony Orchestra (DaCapo)

This handsome box set is a real curio, and a fun one too. It celebrates the musical talents of Denmark’s King Frederik IX (1899-1972), famous for his spare time conducting as well as for the tattoos he acquired during active naval service. Reigning from 1947 to 1972 until his death, he oversaw Denmark’s postwar transformation into a modern state. Frederik’s interest in music was encouraged by his mother Queen Alexandrine, a keen pianist who ensured that her son took lessons from an early age. Frederik conducted his first chamber ensemble as a teenager, honing his self-taught skills and finally conducting a rehearsal with the Royal Danish Orchestra in 1938, the orchestra subsequently holding an annual private concert for him as a recurring birthday gift. Most of the recordings amassed here were made with the Danish National Symphony Orchestra. Transferred from shellac discs and magnetic tape, they play to Frederik’s strengths. Along with some choice Danish novelties, Beethoven and Wagner feature heavily. A 1954 version of Beethoven 7 has plenty of energy, plenty of attention given to Beethoven’s dynamic markings. The playing across the four discs is consistently tight and responsive; Frederik always sounds as if he knows what he’s doing. The Eroica’s first movement is grand and imposing, followed by a similarly weighty funeral march. A 1948 Schubert 8 has a fiery intensity that transcends the scratchy mono sound.

The Wagner excerpts are similarly strong. Best of them is a stoic, powerful 1969 account of Siegfried’s Funeral March, and Frederik’s Flying Dutchman overture benefits from some outstanding brass playing. The rarities are enjoyable. H.C. Lumbye’s Dream Pictures is gorgeous, one of several performances originally released on records raffled off in 1948 to raise money for the United Nations. I’d never heard of the Danish early romantic Friedrich Kuhlau, and we get to hear similarly unheard short pieces by Niels Gade and Hakon Børresen. Frederik’s conducting is unfussy, affectionate but attentive throughout, guests at the private concerts recalling the joy which the King found in his music making. Attractively designed and well-annotated, this is an appealing release.

Add comment