theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2020 – great live orchestra, ecstatic audience | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2020 – great live orchestra, ecstatic audience

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2020 – great live orchestra, ecstatic audience

Estonia’s summer capital buzzes again with electrifying music-making under Paavo Järvi

“At the Pärnu Music Festival 2020” were words I never expected to type. A fortnight ago Estonia finally upped its non-quarantinable country rate from 15 to 16 infections in every 100,000 people (the UK was then on 15.9; our unfathomable Foreign Office has not, to my knowledge, returned the compliment, despite Estonian rates being next to 0 for weeks).

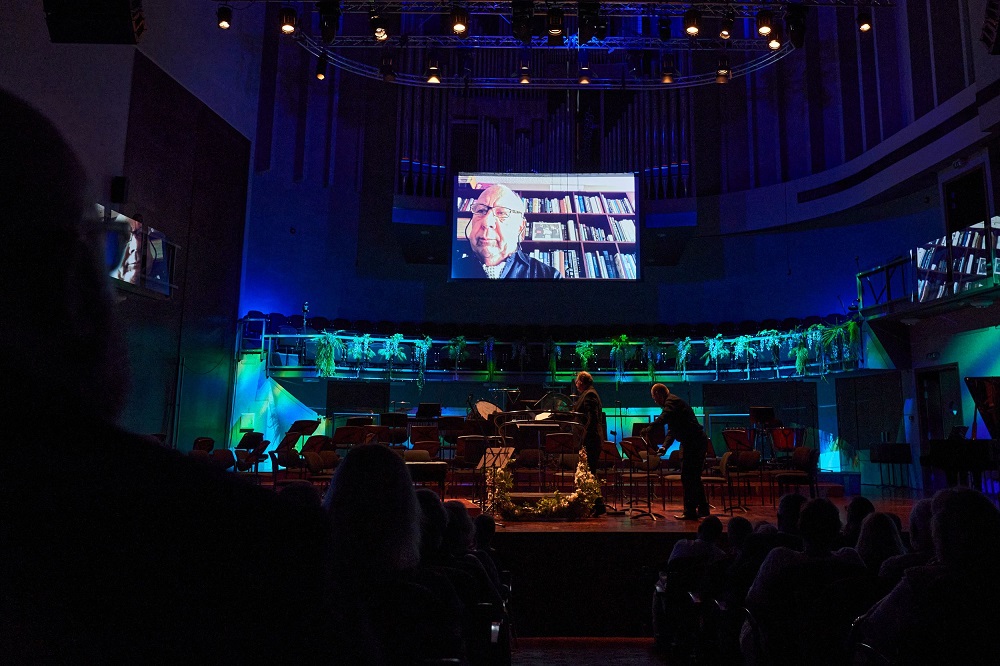

The festival week, in essence, was unchanged in the love and skill of the players, passionately devoted to Paavo Järvi; how easy it was to slip back into the exceptional expected. There were absences, of course: a strict 50 per cent limit on audience attendance, some key players who hadn’t been able to travel from Czechia, Russia and Japan - that meant the percentage of Estonian players in the orchestra was higher than before, and gosh, they're good enough - and while Paavo’s sister Maarika had travelled from Switzerland to join the flute section and his brother Kristjan was helping with sterling work on the conductors’ course, the patriarch of the festival, their father Neeme, 83 last month, was marooned in Florida (ouch) with their mother Liilia. Yet I arrived from Riga at the second half of the Saturday night concert, celebrating 50 years of Pärnu music festivals featuring three orchestras, to see him working the audience with characteristic aplomb from a big screen (pictured below).  What followed was mixed. First came leading Estonian composer Juri Reinvere’s Double Concerto for two flutes, string orchestra and percussion, expanded both in score and string size from when it was premiered here in the chamber hall in 2016; Maarika Järvi, in haunting dialogue with Monika Mattiesen, had quickly learnt a new cadenza. It was heartwarming to see the young Estonians of the Järvi Academy Youth Orchestra, on hand to work with the trainee conductors, take over from the experienced EFO players, but what followed was the only horror of the four days: a Mozart piano sonata movement and numbers from The Magic Flute transfigured by jazz pianist Kristjan Randalu. Or rather disfigured. Prokofiev described Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto, very unfairly but wittily, as “Bach with smallpox”; this was Mozart with coronavirus. Kristjan Järvi’s own piece was sweet but very short, an odd conclusion to a programme which those who’d experienced it all said just hadn’t fitted together.

What followed was mixed. First came leading Estonian composer Juri Reinvere’s Double Concerto for two flutes, string orchestra and percussion, expanded both in score and string size from when it was premiered here in the chamber hall in 2016; Maarika Järvi, in haunting dialogue with Monika Mattiesen, had quickly learnt a new cadenza. It was heartwarming to see the young Estonians of the Järvi Academy Youth Orchestra, on hand to work with the trainee conductors, take over from the experienced EFO players, but what followed was the only horror of the four days: a Mozart piano sonata movement and numbers from The Magic Flute transfigured by jazz pianist Kristjan Randalu. Or rather disfigured. Prokofiev described Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto, very unfairly but wittily, as “Bach with smallpox”; this was Mozart with coronavirus. Kristjan Järvi’s own piece was sweet but very short, an odd conclusion to a programme which those who’d experienced it all said just hadn’t fitted together.

The revelation of the festival hit home in the first of the EFO concerts the following evening. Having shared the bowled-over audience responses to Lepo Sumera’s Fourth and Sixth Symphonies in Tallinn at the Estonian Music Days of 2016 and 2017, and discussed with Paavo how the Fourth would be a knockout success if he and the EFO brought it to the Proms, I was expecting something of an event in the Cello Concerto. Maybe not quite at the level we got. Sumera died in 2000 at the untimely age of 50, and this was one of his last works. The soloist’s often maniacal winding-ups to fever pitch and the haunting, ultimately devastating oscillations of the restless slow movement hint at deep personal distress, akin to the “Anfortas Wound” movement of John Adams’ Harmonielehre, his first work after an 18 month creative block which had brought him close to madness. There is not a cliched idea or sound-combination in the entire concerto, and the finale clinches it all by sailing out into determined melody, only to return to mania and extinction. In its intensity, the work is on a level with Britten's Cello Symphony, Prokofiev's Symphony-Concerto and Shostakovich's Second Cello Concerto. The Estonian National Symphony Orchestra performances of the symphonies under Anu Tali and Kristiina Poska had both been exceptional, and in Poska’s concert we had also been stunned by young cellist-principal Theodor Sink (pictured above in Pärnu rehearsal for the Sumera) in Erkki-Sven Tüür’s Cello Concerto; it wasn’t just the news that Sink’s mother had died the previous week that brought a two-minute silence at the end of the performance. He performed both works from memory; only afterwards did I discover that he didn’t know the Sumera until Paavo Järvi asked him to be the soloist (the conductor also told me that he was familiar with Sink as a hard worker, but now realised he could take him as soloist into any hall and orchestra in the world). The modesty, focus, intensity and collegiality were so obvious in another Sumera work to have an extraordinary impact on its audience. I urge you to watch it on the festival’s TV channel.

The Estonian National Symphony Orchestra performances of the symphonies under Anu Tali and Kristiina Poska had both been exceptional, and in Poska’s concert we had also been stunned by young cellist-principal Theodor Sink (pictured above in Pärnu rehearsal for the Sumera) in Erkki-Sven Tüür’s Cello Concerto; it wasn’t just the news that Sink’s mother had died the previous week that brought a two-minute silence at the end of the performance. He performed both works from memory; only afterwards did I discover that he didn’t know the Sumera until Paavo Järvi asked him to be the soloist (the conductor also told me that he was familiar with Sink as a hard worker, but now realised he could take him as soloist into any hall and orchestra in the world). The modesty, focus, intensity and collegiality were so obvious in another Sumera work to have an extraordinary impact on its audience. I urge you to watch it on the festival’s TV channel.

Focus was officially on a premiere, To the Moonlight, by a living Estonian composer, the always reliable Tõnu Kõrvits. Its hypnotic barcarolles, impressions and pointillistic details seemed to chime with the state of suspension we’ve been living through; it worked its magic in the hall, but is even better in the film, where the colours are visually pinpointed – distant magic from harpist Eda Peäske especially - and Järvi’s clairvoyant manner can be clearly witnessed. In a perfect programme, the sheer robustness of 15-year-old Mendelssohn’s First Symphony made a perfect third work. Even if C minor wasn’t the exuberant teenager’s natural mode, the quirky pizzicati in search of a clarinet tune in the finale and the introspective third-movement trio with its eerie, timpani-punctuated lead back to the scherzo proper – subject to the special brand of chiaroscuro Järvi can conjure from his very own players – are so striking. And the Mozartian wind ensembles of the Andante, handled as a team by some of the world’s best players, again reminded me what I’d been missing so much over the past few months.  So did the Academy Orchestra pounding the Furiant of Dvořák’s happy Sixth Symphony at one of the conductor sessions the next morning: at last, an orchestra at full pelt. That evening, though, it was chamber music in the latest of the galas which have been as much a highlight as the main orchestral concerts. Players’ personalities always have more of a chance to emerge, and this year’s selection of repertoire highlights from the last 10 years blended, as always, faces familiar and (to me, at any rate) new.

So did the Academy Orchestra pounding the Furiant of Dvořák’s happy Sixth Symphony at one of the conductor sessions the next morning: at last, an orchestra at full pelt. That evening, though, it was chamber music in the latest of the galas which have been as much a highlight as the main orchestral concerts. Players’ personalities always have more of a chance to emerge, and this year’s selection of repertoire highlights from the last 10 years blended, as always, faces familiar and (to me, at any rate) new.

Juliane Bruckmann from the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen was such a vivacious, collegial leader of the double basses within the orchestra (pictured above with Siret Lust, Regina Udod and Angie Liang) and stood centre stage in Hasenhõrl’s rudely truncated version of Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel for unorthodox quintet, in which Frank-Gemmill, violinist Emma Yoon and clarinettist Signe Sõmer took the famous solos better than anyone I’ve ever heard.  Staunch leader Florian Donderer (also DKB) made the Mendelssohn Octet fly – I’ve always thought of it as a brilliant piece but usually more earthed – with an unusual team which also included young Estonian Hans Christian Aavik and DKB cellist Thomas Ruge plus regulars Mari Poll, Eva Bindere, Xandi van Dijk, Karin Sarv and Sink. Maarika Järvi adopted the first violin part of Schubert’s B flat major String Trio (here, of course, flute, viola and cello) with Georg Katsouris and Teet Järvi. Hunt’s brilliant partnership in Bartók’s Contrasts with Donderer’s front-desk regular partner Triin Ruubel was repeated, but with the luxury of Olli Mustonen (pictured above with Ruubel and Hunt) taking the place of Sophia Rahman (performing Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time at the end of festival week up in the Arvo Pärt Centre near Tallinn with Hunt and two other players).

Staunch leader Florian Donderer (also DKB) made the Mendelssohn Octet fly – I’ve always thought of it as a brilliant piece but usually more earthed – with an unusual team which also included young Estonian Hans Christian Aavik and DKB cellist Thomas Ruge plus regulars Mari Poll, Eva Bindere, Xandi van Dijk, Karin Sarv and Sink. Maarika Järvi adopted the first violin part of Schubert’s B flat major String Trio (here, of course, flute, viola and cello) with Georg Katsouris and Teet Järvi. Hunt’s brilliant partnership in Bartók’s Contrasts with Donderer’s front-desk regular partner Triin Ruubel was repeated, but with the luxury of Olli Mustonen (pictured above with Ruubel and Hunt) taking the place of Sophia Rahman (performing Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time at the end of festival week up in the Arvo Pärt Centre near Tallinn with Hunt and two other players).

Mustonen’s touch here could be harp-like as well as cimbalom-evocative: a marked contrast to his usual percussive way, which made Beethoven’s own arrangement of his Violin Concerto for piano and orchestra in the penultimate EFO concert seem even further from the lyric original. Mustonen has an odd way of highlighting individual notes which is far from the pearly runs you might expect from an Imogen Cooper, a Paul Lewis or Leif Ove Andsnes in Beethoven, but he made the cadenzas, especially the first-movement spectacular with timpani, leap out as absolutely modern. By Beethoven, really, people asked? Yes, every note.  Another soloist of stunning individuality, Berlin Philharmonic principal horn Stefan Dohr, proved predictably peerless in Mozart’s Third Horn Concerto with the Academy, and took us to another place altogether in the distant gleams of the horn solo from Messiaen’s Des canyons aux étoiles.... It was a bit of a shock, then, to find Dohr the conductor make less than expressive work of Dvořák's first movement. Choosing the best from this year’s line-up of conducting course students seems invidious; some movements would have been worked on harder during the sessions than others, not least the loveliest of Adagios, gleaming in the performance under EFO viola-player-turned-conductor Xandi van Dijk. Undoubtedly the most striking was the emergence of a real conducting personality from an initially tentative impression made in the sessions by Estonian choral conductor Nele Erastus (pictured above) in Dvořák’s Furiant.

Another soloist of stunning individuality, Berlin Philharmonic principal horn Stefan Dohr, proved predictably peerless in Mozart’s Third Horn Concerto with the Academy, and took us to another place altogether in the distant gleams of the horn solo from Messiaen’s Des canyons aux étoiles.... It was a bit of a shock, then, to find Dohr the conductor make less than expressive work of Dvořák's first movement. Choosing the best from this year’s line-up of conducting course students seems invidious; some movements would have been worked on harder during the sessions than others, not least the loveliest of Adagios, gleaming in the performance under EFO viola-player-turned-conductor Xandi van Dijk. Undoubtedly the most striking was the emergence of a real conducting personality from an initially tentative impression made in the sessions by Estonian choral conductor Nele Erastus (pictured above) in Dvořák’s Furiant.

The great symphonic experience was yet to come at the end of the two final EFO programmes. Sumera’s Third Symphony was a welcome opener; my reaction to it might have been slightly more fine-tuned if I’d known that the drifting triads of the Larghetto were the endgame resulting from the previous frenzy, a finale which again brought Adams to mind (this time the metaphysical ending of Nixon in China) as well as the lunar landscape of the "Epilogo" to Vaughan Williams’s Sixth Symphony. But we needed a joyburst at the end of the concert, and I doubt if there has even been a more radiant unleashing of Mozart’s E flat (39th) Symphony than the one Järvi so vividly won from his loving players. Staggering subtlety was here too, above all in the strings’ dropback to pianissimo in the Andante con moto, the most touching major/minor shifts in music before Schubert. But it was Mozart’s cornucopia of invention, the beauty of his tender transitions and his absolute oneness with the world which radiated from every bar.  That, or more specifically the usual charge of the encores - two per EFO concert until the very last night, when there were three - was the live conclusion for me of a blissful four days which also included the familiar walks along the sandy bay and swims in a warm sea, café life at its most relaxed and meetings with wonderful people. But praise be to technology that when I arrived home in London, I could just catch a violinist who, when I met her after her first rehearsal with the orchestra, clearly embodied the true Pärnu spirit, Alena Baeva – coming from Luxembourg, she'd self-quarantined in Germany for two weeks to play in the final concert – in Strauss’s Violin Concerto (pictured above), made worthwhile by its tarantella finale but all of it beautifully articulated, and watch the Mozart symphony again, given one extra twist by the peerless Hunt’s little ornamentation in the minuet trio. You can witness the miracle, too, for a month; don’t miss the EFO concerts or the chamber gems. Music-making as an expression of sheer love from the very best players can never soar higher than this.

That, or more specifically the usual charge of the encores - two per EFO concert until the very last night, when there were three - was the live conclusion for me of a blissful four days which also included the familiar walks along the sandy bay and swims in a warm sea, café life at its most relaxed and meetings with wonderful people. But praise be to technology that when I arrived home in London, I could just catch a violinist who, when I met her after her first rehearsal with the orchestra, clearly embodied the true Pärnu spirit, Alena Baeva – coming from Luxembourg, she'd self-quarantined in Germany for two weeks to play in the final concert – in Strauss’s Violin Concerto (pictured above), made worthwhile by its tarantella finale but all of it beautifully articulated, and watch the Mozart symphony again, given one extra twist by the peerless Hunt’s little ornamentation in the minuet trio. You can witness the miracle, too, for a month; don’t miss the EFO concerts or the chamber gems. Music-making as an expression of sheer love from the very best players can never soar higher than this.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Add comment