A new Estonian musical golden age is now reaping the benefits of a superlative musical education system, but experience also counts: the central force that makes this festival the most welcoming I’ve ever experienced, Paavo Järvi, will be 60 this year; father Neeme, back in Estonia’s lovely summer capital by the Baltic after two years’ enforced absence, and brother Kristjan marked their respective 85th and 50th birthdays in June (Paavo pictured below by Tõiv Jõul with players of the Estonian Festival Orchestra). Other dedicated wisdom is international: friends of Paavo in leading positions with top orchestras around the world are here not just to play alongside native talent in the dream ensemble that is the Estonian Festival Orchestra, a Utopian ensemble that comes together every summer, but also to teach the young conductors and players of the Academy Orchestra, waxing ever finer. This time, having attended many of the conducting and instrumental masterclasses on previous occasions, I experienced only the rewards of all that hard work in five stupendous concerts, in music ranging from Biber to Estonian composer Mari Vihmand, from violin solo to roof-raising orchestral Sibelius and Tchaikovsky.

Other dedicated wisdom is international: friends of Paavo in leading positions with top orchestras around the world are here not just to play alongside native talent in the dream ensemble that is the Estonian Festival Orchestra, a Utopian ensemble that comes together every summer, but also to teach the young conductors and players of the Academy Orchestra, waxing ever finer. This time, having attended many of the conducting and instrumental masterclasses on previous occasions, I experienced only the rewards of all that hard work in five stupendous concerts, in music ranging from Biber to Estonian composer Mari Vihmand, from violin solo to roof-raising orchestral Sibelius and Tchaikovsky.

Having regretfully missed Neeme conducting the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra at the opening concert, and Kristjan bringing his Baltic Sea Philharmonic to the festival for the first time, I was at least able to follow the usual pattern – two of the essential concerts with Paavo and his army of EFO generals who form the reason for the festival’s existence, the unmissable chamber concert showcasing key players of that musical family, and the big event – never bigger than this year – in which young conductors of the Järvi Academy course go through their paces with the Academy’s ever more miraculous Youth Symphony Orchestra.  The first notes I heard proved why we need the best players, and the most ardent spirit, to make everything work. Previous impressions of Lutosławski’s 1958 Musique funèbre had been of something grey and unnecessarily thorny. But starting with the cello section of the EFO, never finer, the string articulation here was a matter of life and death, and just why was clear in Paavo’s spoken introduction: the performance was dedicated to the victims of the atrocities in Ukraine (it goes without saying, of course, that no country identifies more strongly with Ukraine than Estonia). Watching the previous evening’s concerto performance on the Pärnu Music Festival TV channel – every event is filmed for free viewing (donations welcome), and the archive is already impressive – I wished I’d been there for a concerto I love, Strauss’s Second for horn, played, or rather sung, by the peerless Stefan Dohr. Bruch’s First Violin Concerto only works for me if it’s unfolded with all the naturalness in the world, which is why I found the full-octane energy of Joshua Bell and the EFO players a little too much (though Bell’s performance of the Dvořák last year was thrilling. Bell pictured above by Taavi Kull with Paavo Järvi in rehearsal).

The first notes I heard proved why we need the best players, and the most ardent spirit, to make everything work. Previous impressions of Lutosławski’s 1958 Musique funèbre had been of something grey and unnecessarily thorny. But starting with the cello section of the EFO, never finer, the string articulation here was a matter of life and death, and just why was clear in Paavo’s spoken introduction: the performance was dedicated to the victims of the atrocities in Ukraine (it goes without saying, of course, that no country identifies more strongly with Ukraine than Estonia). Watching the previous evening’s concerto performance on the Pärnu Music Festival TV channel – every event is filmed for free viewing (donations welcome), and the archive is already impressive – I wished I’d been there for a concerto I love, Strauss’s Second for horn, played, or rather sung, by the peerless Stefan Dohr. Bruch’s First Violin Concerto only works for me if it’s unfolded with all the naturalness in the world, which is why I found the full-octane energy of Joshua Bell and the EFO players a little too much (though Bell’s performance of the Dvořák last year was thrilling. Bell pictured above by Taavi Kull with Paavo Järvi in rehearsal).

That’s a question of taste; similarly with Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony, where Paavo’s elasticity with the tempi went to more emphatic extremes than I’d have liked in a first movement which was more one of buffets and ecstasies than the onward march of fate-as-providence with incidental consolations. But what rightful mastery in the Andante cantabile: there isn’t a horn player in the world who can unfold the first main theme better than EFO regular Alec Frank-Gemmill (and there were some supremely spooky stopped-horn effects from Björn Olsson in the not quite straightforward waltz). The finale flamed at slightly deafening close quarters, but magnificently; and there was perfect play with the polonaise rhythms of the grand number which begins Act Three of Eugene Onegin.

There was every reason to look forward to Monday evening’s intermezzo of charmers from Biber and Vivaldi, featuring treasures from the Estonian Foundation of Musical Instruments; but it excelled expectations. Twenty-four-year-old Estonian Hans Christian Aavik, who’s already appeared with the EFO and in a 2020 performance of the Mendelssohn Octet, and now has a special feather in his cap as the winner of the violin prize at the 2022 Carl Nielsen International Competition, produced a silvery flow of sheer delight in Biber’s Sonata Representativa (1669) with cellist Theodor Sink (star of 2020) and harpsichordist Reinut Tepp. Nightingale, cuckoo, frog, cock and hen, quail and cat all figured in one short, perfect work; Biber’s modernity cued some jamming, too. For The Four Seasons there was the winning idea of giving each of the concertos to each of four soloists, both young and experienced; Aavik was bound to run away with the originality here, but EFO leader Florian Donderer seemed to be conjuring improvisations on the spot in tricky “Autumn”. All of it fleet, direct and unhackneyed from a perfect ensemble.

There was every reason to look forward to Monday evening’s intermezzo of charmers from Biber and Vivaldi, featuring treasures from the Estonian Foundation of Musical Instruments; but it excelled expectations. Twenty-four-year-old Estonian Hans Christian Aavik, who’s already appeared with the EFO and in a 2020 performance of the Mendelssohn Octet, and now has a special feather in his cap as the winner of the violin prize at the 2022 Carl Nielsen International Competition, produced a silvery flow of sheer delight in Biber’s Sonata Representativa (1669) with cellist Theodor Sink (star of 2020) and harpsichordist Reinut Tepp. Nightingale, cuckoo, frog, cock and hen, quail and cat all figured in one short, perfect work; Biber’s modernity cued some jamming, too. For The Four Seasons there was the winning idea of giving each of the concertos to each of four soloists, both young and experienced; Aavik was bound to run away with the originality here, but EFO leader Florian Donderer seemed to be conjuring improvisations on the spot in tricky “Autumn”. All of it fleet, direct and unhackneyed from a perfect ensemble.

Aavik dazzled again in the chamber music gala the following night, this time in the company of his partner, in both music and life, Karolina Žukova, in the phantasmagorical dance finale of one of the 20th century’s greatest and most original sonatas for piano and violin, Enescu’s Third (pictured above by Taavi Kull). You wonder how hard they’d had to work on this to reach such a level: and what a shame that given recent curtailments of festival galas they weren’t permitted to play the whole thing: at the Wigmore Hall, soon, is an event devoutly to be wished.  I’d also love to have heard all five movements of the Fourth String Quartet by major Ukrainian composer Lyatoshinsky (teacher of Silvestrov). Both the native folk-songs he chooses and the original quartet treatment of them are first-rate, starting with the gorgeous cello song delivered exquisitely here by Benjamin Nyffenegger. The mover here was Lyatoshinsky’s compatriot and long-serving violinist in the EFO, Artur Podlesniy; poignantly, Podlesniy is from Kharkiv, and though his parents have been able to join him in Frankfurt, there are still concerns for the wider family. (Pictured above by Taavi Kull: Podlesniy, Grace Kyung Eun Lee, Mari Adachi and Nyffenegger).

I’d also love to have heard all five movements of the Fourth String Quartet by major Ukrainian composer Lyatoshinsky (teacher of Silvestrov). Both the native folk-songs he chooses and the original quartet treatment of them are first-rate, starting with the gorgeous cello song delivered exquisitely here by Benjamin Nyffenegger. The mover here was Lyatoshinsky’s compatriot and long-serving violinist in the EFO, Artur Podlesniy; poignantly, Podlesniy is from Kharkiv, and though his parents have been able to join him in Frankfurt, there are still concerns for the wider family. (Pictured above by Taavi Kull: Podlesniy, Grace Kyung Eun Lee, Mari Adachi and Nyffenegger).

There were no weak links in this programme, and much to learn. Benjamin Baker opened the concert with the tough and brilliant solo violin sonata by one of Estonia’s top composers, Eduard Tubin; despite the awkward intervals and material never quite returning the same, the utter conviction was stunning. For some reason I’ve also not heard Dvořák C major String Trio in concert; it was subtly and lovingly delivered by a couple new to the EFO, Eugenia and Gilad Karmi, and Emma Yoon..  In the absence of several star players this year, not least regular clarinettist Matt Hunt, the extrovert Karmi made some amends, and I haven’t seen bassoonist Martin Kuuskmann since he played Prince-Beast to Hunt’s Princess in Strauss’s Duett-Concertino in 2015: some amazing sounds from him and another consummate pianist, Kärt Ruubel, in Kuuskmann’s arrangement of Erkki-Sven Tüür’s Dedication (bassoonist and pianist pictured above by Taavi Kull). The grand finale looked dodgy on paper – Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings arranged for four cellos – and lower-register sounds, especially in the first movement, just felt wrong. But what four cellists we had here, all of them singing the melody of the "Élégie" to perfection: ineffable master Thomas Ruge, Nyffenegger, Sink and 27-year-old Marcel Johannes Kits.

In the absence of several star players this year, not least regular clarinettist Matt Hunt, the extrovert Karmi made some amends, and I haven’t seen bassoonist Martin Kuuskmann since he played Prince-Beast to Hunt’s Princess in Strauss’s Duett-Concertino in 2015: some amazing sounds from him and another consummate pianist, Kärt Ruubel, in Kuuskmann’s arrangement of Erkki-Sven Tüür’s Dedication (bassoonist and pianist pictured above by Taavi Kull). The grand finale looked dodgy on paper – Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings arranged for four cellos – and lower-register sounds, especially in the first movement, just felt wrong. But what four cellists we had here, all of them singing the melody of the "Élégie" to perfection: ineffable master Thomas Ruge, Nyffenegger, Sink and 27-year-old Marcel Johannes Kits.

Nearly four hours and two intervals used to be the running time of festival chamber galas. This year it was the turn of the Academy special, in order – for the first time ever – to allow all 19 young conductors a movement each. That even meant having every movement of Haydn’s endlessly inventive Symphony No 95 performed twice in the central panel of the triptych – a decision which actually worked in practice, with fascinating contrasts to be drawn and at least three top conductors emerging, Kristian Sallinen in the Menuetto and Jakub Przybycien; in the once-through-only Schumann Four – much the trickiest work for the players – there were fine things from Margarita Balanas in the Scherzo and Dorian Todorov (an exciting breakthrough) in the Finale.  Yet though the audience and the orchestra got to choose its favourite, this was no competition and it wasn’t really possible to judge the artistry in Vihmand’s rather static and repetitive Triple Concerto, despite consummate work from flautists Maarika Järvi and Monika Mattiesen and bassoonist Kuuskmann again.

Yet though the audience and the orchestra got to choose its favourite, this was no competition and it wasn’t really possible to judge the artistry in Vihmand’s rather static and repetitive Triple Concerto, despite consummate work from flautists Maarika Järvi and Monika Mattiesen and bassoonist Kuuskmann again.

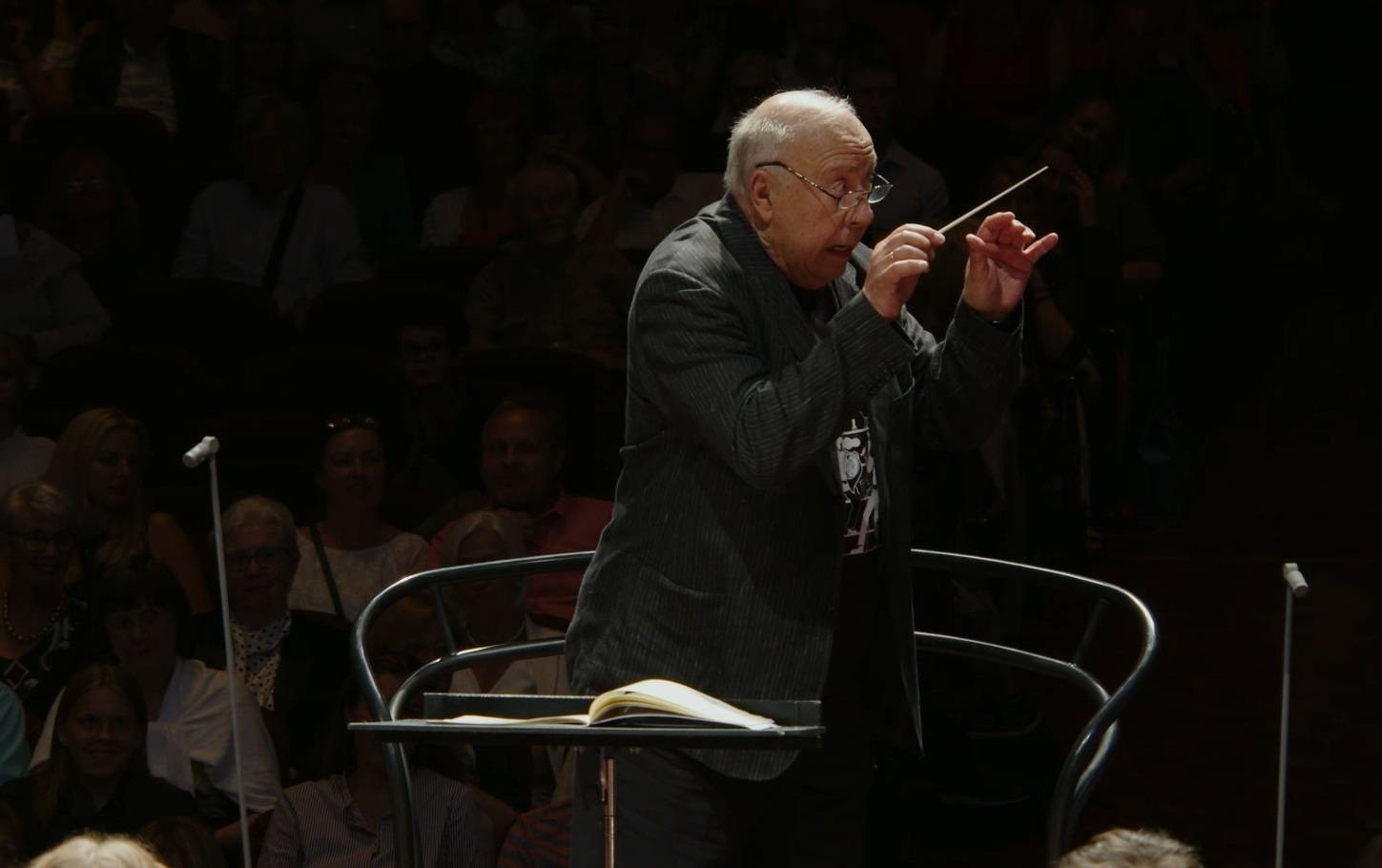

There were two performances of Tubin’s Prélude Solennel, impressive at the start under Nelle Eraste, the conductor I thought made the most progress two years ago, and very authoritative from 15-year-old Kasper Joel Nõgene – no timebeater he, no freakshow, but clearly a real talent (pictured above on the left as Paavo goes along the line to congratulate the conductors).  The most delicious playing of the evening was the incredibly authentic Viennese lilt – not easy to capture by players young or old – in Josef Strauss’s Dynamiden Waltz, the obvious model for the Rosenkavalier hit of Richard (no relation). Jaehyuck Choi had the idiom off to a tee, so there was no real overshadowing when Neeme took up the baton at the end for another masterclass in teasing waltz-magic: an obvious highlight of the week for anyone who adores this master (as who could not? Pictured above: holding the upbeat to the famous melody)

The most delicious playing of the evening was the incredibly authentic Viennese lilt – not easy to capture by players young or old – in Josef Strauss’s Dynamiden Waltz, the obvious model for the Rosenkavalier hit of Richard (no relation). Jaehyuck Choi had the idiom off to a tee, so there was no real overshadowing when Neeme took up the baton at the end for another masterclass in teasing waltz-magic: an obvious highlight of the week for anyone who adores this master (as who could not? Pictured above: holding the upbeat to the famous melody)

A final unexpected turn from the patriarch at the very last concert of the festival, where I saw on film how Paavo handed the stick over to dad to conduct “his” orchestra in a regular encore, Sibelius’s Andante festivo, made me regret not having been able to stay one more night; likewise the pacy brilliance of Paavo and the EFO keeping tabs on Wayne Marshall in Gershwin’s Piano Concerto (pictured below by Tõiv Jõul), full of lovely and, in the middle movement, substantial improvisational touches, even more beautifully done in a solo encore which wedded the opening of Sibelius Two with “Happy Birthday”. Still, I got a differently moving concerto performance, showcasing more great Estonians in the Brahms Double: Triin Ruubel, world-class leader of the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra and recorded interpreter, with Neeme Jarvi and the orchestra, of what I think is the best Elgar Violin Concerto since Kennedy’s first shot; and Marcel Johannes Kits, both rising from chamber-musical intimacy to elevated grandeur (after the performance, pictured below by Tõiv Jõul , with EFO leader Florian Donderer looking on).

Still, I got a differently moving concerto performance, showcasing more great Estonians in the Brahms Double: Triin Ruubel, world-class leader of the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra and recorded interpreter, with Neeme Jarvi and the orchestra, of what I think is the best Elgar Violin Concerto since Kennedy’s first shot; and Marcel Johannes Kits, both rising from chamber-musical intimacy to elevated grandeur (after the performance, pictured below by Tõiv Jõul , with EFO leader Florian Donderer looking on).

The opener this time (and on the Friday) was Grazyna Bacewicz’s Concerto for String Orchestra, never sounding more finely textured, rhythmically alert or thematically striking – a beacon in the murky sea of post-World War Two string works. Good to know that it's been included in the EFO's latest recording schedule. For the epic, world-embracing final gambit, Paavo Järvi championed Sibelius’s early Lemminkäinen Suite – would it do better if, as he later thought he should have done, he’d called it a symphony? The adventures of the erotomanic hero of the Kalevala in a Tristanesque drama of love and death sounded so vivid, as individual a masterpiece as Sibelius ever penned; and the ppp(pp) mythic ghost of eight-part violins at the heart of what this time sounded like the most extraordinary movement, “Lemminkäinen in Tuonela”, was what the players call a “Paavo moment”, like the barely-audible major shuffles in his most impressive encore, Valse Triste – which we got again, after a hyper-flexible Brahms Hungarian Dance No. 1. Of course I regretted not staying to see the final glory, Neeme conducting his most celebrated encore, Sibelius’s Andante festivo, but you can’t do everything, and that moment of history is there on the TV channel, too.

For the epic, world-embracing final gambit, Paavo Järvi championed Sibelius’s early Lemminkäinen Suite – would it do better if, as he later thought he should have done, he’d called it a symphony? The adventures of the erotomanic hero of the Kalevala in a Tristanesque drama of love and death sounded so vivid, as individual a masterpiece as Sibelius ever penned; and the ppp(pp) mythic ghost of eight-part violins at the heart of what this time sounded like the most extraordinary movement, “Lemminkäinen in Tuonela”, was what the players call a “Paavo moment”, like the barely-audible major shuffles in his most impressive encore, Valse Triste – which we got again, after a hyper-flexible Brahms Hungarian Dance No. 1. Of course I regretted not staying to see the final glory, Neeme conducting his most celebrated encore, Sibelius’s Andante festivo, but you can’t do everything, and that moment of history is there on the TV channel, too.

Add comment