Anxiety, injustice and desperate disorder are the themes of these six disparate noirs. In one, The Dark Past, Lee J. Cobb’s psychiatrist draws a crude diagram of the brain with a line dividing the conscious and unconscious, and these films visit the choppy depths under the surface calm of suburban Cold War America, its terrors in the night.

Venturing beyond the obvious classics, Columbia Noir #3 shows the range and intensity of Hollywood’s response to the post-war malaise. Often blighted by the House Un-American Activities Committee’s anti-communist witch-hunts, and increasingly shot in real streets, this cinema is part of the country’s condition. It describes a sick society that thinks it can be cured, as psychopaths and psychiatrists, delinquents and detectives duel.

Between Midnight and Dawn (1950) borrows the documentary trappings of The Naked City (1948), with its call-centre codes and prowl-cars. Director Gordon Douglas - a talented journeyman later responsible for good Sinatra thrillers and the atomic horror of giant ants in Them! (1954) – hurls car chases down urban and country back-streets, as if escaping into his unnamed city’s unconscious hinterland.

The realistic veneer is undermined by the plot’s melodrama, and folksy banter between veteran cop “Pappy” Purvis (burly Edmond O’Brien) and easygoing partner Rocky (Mark Stevens). But listen as these Pacific war veterans keep talking, and the blunt force beneath Fifties conformity hits home. “Wait’ll you’ve had your fill of the scum,” Purvis sneers of a weeping young female accomplice. Slapping a female singer later, he explains: “The only thing these hoodlums understand is an iron fist.” Orphaned Irish cop’s daughter Kate Mallory (Gale Stevens) passionately disagrees, in words which cross the decades: “A brutal policeman is a terrible thing. He has too much power.”

But outside this debate on reform struts young gangster Ritchie Garris (Donald Bucka), a sawdust Caesar with the Emperor’s face on his wall, thin-skinned and baby-faced, his body tense with nerves and vanity. Bucka makes him truly dangerous, a monster from the urban id repeatedly incarnated across these six noirs. Thanks to him and the deceptively full-blooded script, a hero dies, a redeemed “bad” girl is bloodily gut-shot, and a child dangled from a high window. A happy, liberal ending can’t erase the chaos.

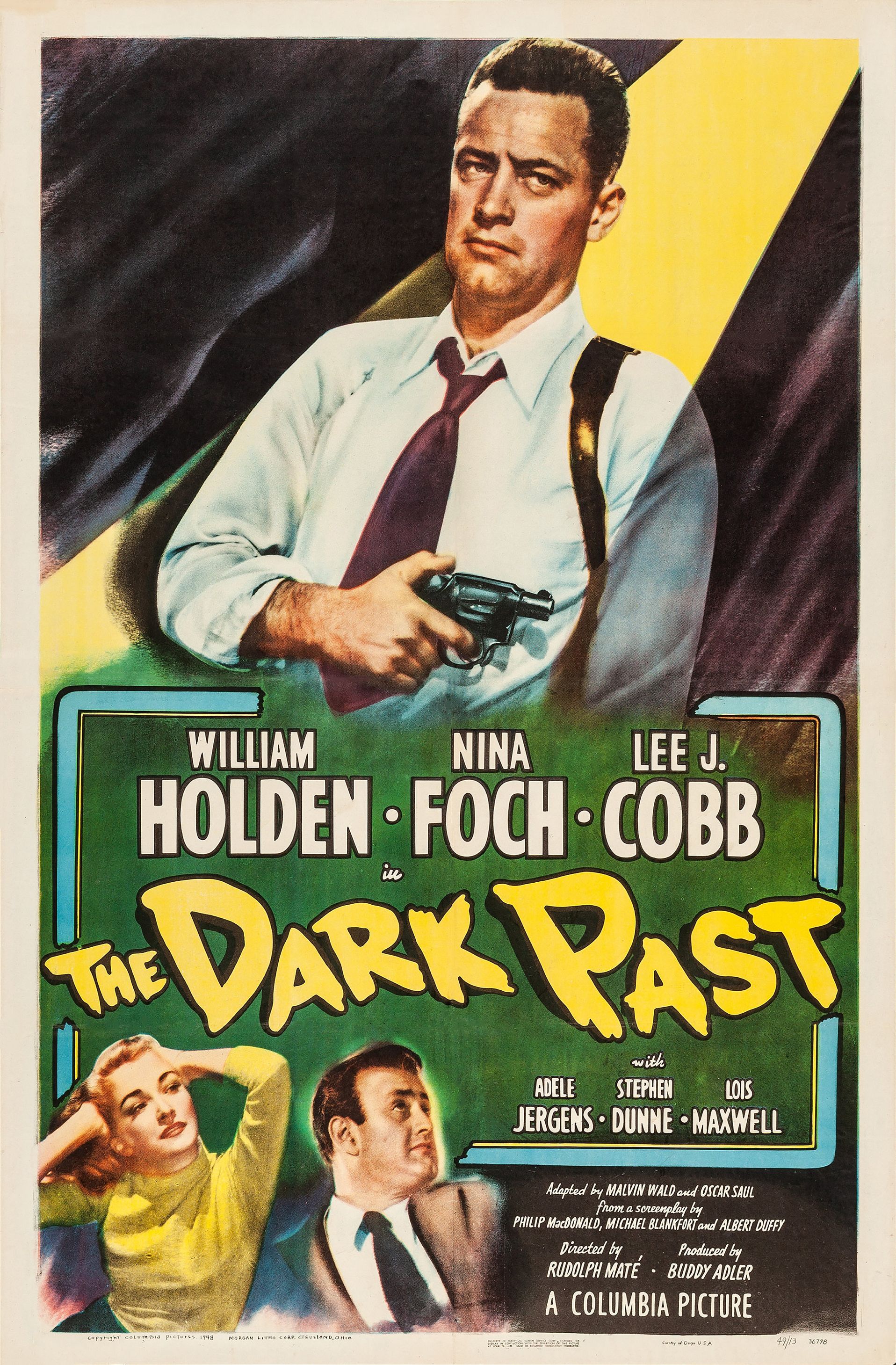

In The Dark Past (1949), Lee J. Cobb is a stretch as pipe-smoking psychologist Collins, whose dinner party is invaded by the gang of escaped killer Walker (William Holden), including Nina Foch’s coolly understated, mothering moll. Cobb’s inherent authority and menace neutralises the threat in later home invasion thrillers such as The Desperate Hours (1955), or Edward G. Robinson’s prior, pistol-enforced stay with Bogie in Key Largo (1948). His confidence is reinforced by his character’s place at society’s top, and the film’s conviction that psychiatry is a panacea if we’ll just take our dose, much as hippies viewed LSD.

In The Dark Past (1949), Lee J. Cobb is a stretch as pipe-smoking psychologist Collins, whose dinner party is invaded by the gang of escaped killer Walker (William Holden), including Nina Foch’s coolly understated, mothering moll. Cobb’s inherent authority and menace neutralises the threat in later home invasion thrillers such as The Desperate Hours (1955), or Edward G. Robinson’s prior, pistol-enforced stay with Bogie in Key Largo (1948). His confidence is reinforced by his character’s place at society’s top, and the film’s conviction that psychiatry is a panacea if we’ll just take our dose, much as hippies viewed LSD.

Again, though, we’re attracted to Holden’s lean, wired, sullen hood (and cool Nina by his side). He handles a copy of The Sociological Aspect of Insanity like an unexploded bomb, afraid of its answers, and when Collins digs up a symbolic nightmare of patriarchal betrayal, remembered in X-ray negative, Holden’s pained, set face is childishly earnest as he regresses. If you only know him for the drink-ravaged later years of The Wild Bunch, this committed, naturalistic performance is a revelation. Disarmed by Collins’ cure, his killer’s cool anyway goes too, his reward, we imagine, the electric chair. The moral is again one of optimistic improvement. “There, with a little difference in the basic human equation, goes any one of us,” the good doctor muses. Despite the many corpses coldly left in his wake, its Holden’s Walker, a bloody premonition of parentally tortured James Dean, who holds our sympathy.

Convicted (1950) has similarly contrasting stars, and half-hearted belief in reform. As lawyer George Knowland, Broderick Crawford, fresh from his Oscar as populist Senator Willie Long in All the King’s Men (1949), is a big, tough man, a real-life hard-drinker looking much older than his 38 years, with bullish energy, light feet, and a capacity for softness. He reluctantly gets Okinawa war hero Joe (Glenn Ford) convicted for the accidental killing of a judge’s son in a nightclub row; Ford is still sitting at his table when the cops arrive, boyish and lost. Five years of jail make him sullen. “I haven’t let anything happen, it’s just gone ahead and done it,” he snaps, noir fatalism, a form of blues, crushing him. Director Henry Levin films the prison yard like a refugee camp, and stokes a sense of bitter injustice (today’s corrupt industrial jails are seen in outline). Suburban acceptance, not psychiatry, leads to happiness here.

Edward Dmytryk’s The Sniper (1952) takes the Fifties’ belief in scientific redemption to the outer limits, with a young misogynist serial killer protagonist, almost a decade before Peeping Tom effectively ended Michael Powell’s career.

Edward Dmytryk’s The Sniper (1952) takes the Fifties’ belief in scientific redemption to the outer limits, with a young misogynist serial killer protagonist, almost a decade before Peeping Tom effectively ended Michael Powell’s career.

Laundry worker Edward (Arthur Franz) is the unassuming, awkward war veteran who watches women from his room through a rifle sight. As Hitchcock knew, the camera’s viewpoint lures us into identifying with his voyeuristic, long-distance power. Dmytryk films on San Francisco’s nightmare-angled slopes, German Expressionism meeting documentary realism in noir America. Here a customer of Edward’s who’s mildly slighted him, nightclub singer Jean (Marie Windsor, pictured above with Franz), walks through barely lit streets to work at the Paper Doll (a real gay nightclub). She has a warm exchange with her kindly boss, glances at her poster. Then her head suddenly smashes into its glass, Dmytryk showing the shocking violence of Edward’s gun. There’s another smug police psychologist to explain it all, hands in pockets, early cure or jail his path to ending male violence. Meanwhile, uncomfortable Arthur escalates his spree. What’s more symptomatic and disturbing, though, is the endemic misogyny in Edna and Edward Anhalt’s script, from the woman dunked as a fairground prize to callous banter. In an Extra, Martin Scorsese remembers seeing The Sniper aged 10, and feeling “unsafe”. It hung around small New York cinemas, its attraction select but potent.

City of Fear (1959) is at the end of noir’s line, a terminal film. Director Irving Lerner starts with an ambulance speeding down back-roads, at its wheel Vince Ryker (Vince Edwards), two dead back at his jailbreak, his partner soon following, and a canister of what he thinks is heroin in his hand. In fact it’s Cobalt-60, a radioactive poison the authorities were testing on prisoners. Vince isn’t just personally dangerous but a walking plague, vanishing from the desperate authorities into cheap motels where the coin-op radio plays cool jazz. Edwards is another magnetic, under-sung performer, later a star as TV doctor Ben Casey, before gambling ruined him. Disguised in a murdered man’s civilised hat and spectacles, he has Mark Ruffalo’s edgy, queasy respectability. Sensually macho in reality, he could be James Caan. And he’s sweating worse and worse, a ruthless killer who’s also a victim. “TERMITES RATS ROACHES” a billboard says above him and, like Harry Lime, his social pestilence is run to ground. Lerner films in Los Angeles’ anonymous sprawl, and Jerry Goldsmith’s jittery, avant-jazz score adds to the feeling that the whole film is diseased, Cobalt-60 the symptom of a nuclear-dreading nation, sweating under the covers.

City of Fear (1959) is at the end of noir’s line, a terminal film. Director Irving Lerner starts with an ambulance speeding down back-roads, at its wheel Vince Ryker (Vince Edwards), two dead back at his jailbreak, his partner soon following, and a canister of what he thinks is heroin in his hand. In fact it’s Cobalt-60, a radioactive poison the authorities were testing on prisoners. Vince isn’t just personally dangerous but a walking plague, vanishing from the desperate authorities into cheap motels where the coin-op radio plays cool jazz. Edwards is another magnetic, under-sung performer, later a star as TV doctor Ben Casey, before gambling ruined him. Disguised in a murdered man’s civilised hat and spectacles, he has Mark Ruffalo’s edgy, queasy respectability. Sensually macho in reality, he could be James Caan. And he’s sweating worse and worse, a ruthless killer who’s also a victim. “TERMITES RATS ROACHES” a billboard says above him and, like Harry Lime, his social pestilence is run to ground. Lerner films in Los Angeles’ anonymous sprawl, and Jerry Goldsmith’s jittery, avant-jazz score adds to the feeling that the whole film is diseased, Cobalt-60 the symptom of a nuclear-dreading nation, sweating under the covers.

Robert Rossen’s Johnny O’Clock (1947) is the closest to classic film noir, with its wise-guys, femme fatales and fatalism. Lee J. Cobb is back in his element as dogged Detective Koch. He’s hunting casino co-owner Johnny O’Clock, who has more names than suits, and as played by Dick Powell (a Thirties musical star getting a second wind as tough guys) is rumpled and sallow from a sunless life. Nina Foch’s latest quietly intelligent turn as hat-check girl Harriet ends her “22 quick years” in murder. Sister Nancy (Evelyn Keyes, pictured above with Powell) investigates, softening Johnny’s hard-boiled shell at one bar with shots and blues music (“That’s low-down and mean,” she murmurs), then getting out of the rain after a missed flight at Joe’s Cocktails. Powell and Keyes make it a real relationship as she drags on his cigarette. She’s another war victim, her boyfriend dead. “No place to go,” she tells him with fathomless need. In the background there are rooming houses, a vast casino with real Vegas gear, and gangster’s moll Nelle (Ellen Drew), poured into her dress but drinking grimly. Though Johnny O’Clock operates in a genre dreamland, it includes the hard poetry Rossen ultimately brought to The Hustler (1961).

Robert Rossen’s Johnny O’Clock (1947) is the closest to classic film noir, with its wise-guys, femme fatales and fatalism. Lee J. Cobb is back in his element as dogged Detective Koch. He’s hunting casino co-owner Johnny O’Clock, who has more names than suits, and as played by Dick Powell (a Thirties musical star getting a second wind as tough guys) is rumpled and sallow from a sunless life. Nina Foch’s latest quietly intelligent turn as hat-check girl Harriet ends her “22 quick years” in murder. Sister Nancy (Evelyn Keyes, pictured above with Powell) investigates, softening Johnny’s hard-boiled shell at one bar with shots and blues music (“That’s low-down and mean,” she murmurs), then getting out of the rain after a missed flight at Joe’s Cocktails. Powell and Keyes make it a real relationship as she drags on his cigarette. She’s another war victim, her boyfriend dead. “No place to go,” she tells him with fathomless need. In the background there are rooming houses, a vast casino with real Vegas gear, and gangster’s moll Nelle (Ellen Drew), poured into her dress but drinking grimly. Though Johnny O’Clock operates in a genre dreamland, it includes the hard poetry Rossen ultimately brought to The Hustler (1961).

These six discs’ exhaustive extras include mostly very informative critics’ commentaries, filling in Hollywood Blacklist lacunae and sometimes painful, career-saving betrayals in the lives of Rossen, Dmytryk, and Irving Lerner (who was actually caught in likely Soviet espionage). As Otto Friedrich’s book on Forties Hollywood, City of Nets (1986), also makes clear, war, paranoia and duplicity were in the air these films breathed. Short documentaries (including one on Nina Foch), appreciations from Scorsese and Christopher Nolan, short films by these films’ makers often supporting Jewish refugees, and even appropriate Three Stooges shorts complete the supporting bill.

Add comment