It was very odd, in January this year, to see that Super-8 camera of Derek’s in a glass case and a few open notebooks in his beautiful italic handwriting in some other glass cases in the same room. There were five or six small-scale projections from his films in other rooms, including The Last of England, and some art works, but, somehow, Derek wasn’t there at all for me.

The location where all these things were turned into what felt like sacred relics was the Inigo Rooms at Somerset House and the exhibition was Derek Jarman: Pandemonium. Pandemonium didn’t sound so out of place in relation to Derek’s work but this exhibition was anything but that.

I fight for a space for independent thought and film; not all the space, but a little for a cinema of small but nevertheless burning gestures for a true British cinema

From Derek Jarman's 1984 "Manifesto"

I’m not sure you can blame anyone. It’s 20 years since Derek died and people want to remember him, bring him back, reveal him to a new generation, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But those rooms in Somerset House were too small, too tidy. It was as if Derek had been shrunken, pickled and embalmed. Even The Last of England lost its roar in these surroundings.

Perhaps at the BFI Southbank (still the NFT for my generation) and other venues where his work is being shown on the big screen, the films themselves will come back with all their power and imagination. The films, after all, are the main things now and no one else made anything quite like them.

But somehow, in the Inigo Rooms, it was Derek tamed, catalogued, glass-cased. Even when I saw his body in Prospect Cottage, on the day of his funeral, he never seemed as dead as at Somerset House.

I was lucky. Very lucky. I knew him. Was encouraged and helped by him. Made a number of films living through the same times as him. He made Sebastiane and soon after I made, with Paul Hallam, Nighthawks. Two films about homosexuality when it was still a taboo subject in the UK. He made The Last of England and I made, with Mark Ayres, Empire State. Both reactions to Thatcher’s Britain. We both made diary and journal films. We both wrote and read our own narrations. Our ultimate concerns were perhaps not so very different and even some of our methods were not so very dissimilar. We both liked working with “non-professionals”, with people who were part of our ordinary daily life. One thing I respected above all else about Derek was the lack of contradiction between his personal and his public life. His life and work were always one, it seemed to me, and urgently so in his later years.

He was a man who expressed himself directly and without compromise. I was sitting next to him once at a preview screening by the BFI of Peter Greenaway’s A Zed and Two Noughts. All through the film I was aware of Derek getting angrier and angrier, almost rocking with anger in his seat. The film ended, there were the usual first polite comments and then Derek stood up and said, with great passion, “But it’s dead, dead, dead!” I have always remembered that moment and that outcry. Two of the giants of the independent film world suddenly in direct opposition, one man all passion, the other, on the evidence of the film, all calculation. There was something heroic, egotistical and brave about that gesture.

He was a man who expressed himself directly and without compromise. I was sitting next to him once at a preview screening by the BFI of Peter Greenaway’s A Zed and Two Noughts. All through the film I was aware of Derek getting angrier and angrier, almost rocking with anger in his seat. The film ended, there were the usual first polite comments and then Derek stood up and said, with great passion, “But it’s dead, dead, dead!” I have always remembered that moment and that outcry. Two of the giants of the independent film world suddenly in direct opposition, one man all passion, the other, on the evidence of the film, all calculation. There was something heroic, egotistical and brave about that gesture.

If Greenaway was felt by some as the new machine, the filmmaker-as-computer, perhaps even the clean-cut technological future, Derek was the revenging upsurge of the four elements – fire, earth, air and water. They rush through all his work, never more furiously than through The Last of England, for me his strongest piece, along with Blue. (Pictured, above: Tilda Swinton in The Last of England). “Elemental” is certainly another word that comes to mind in remembering Derek’s work. The sea, the sky, the raging fires, the fragile flowers and the landscapes, the sense of historical roots, the intense passion for writing and literature, for making and creating, the sheer anger at the state of things… these burst out of his films without restraint.

He managed with so little. I just re-read that incredibly moving 1982 inventory at the end of his book Dancing Ledge where he counts the pennies he survived on. That small room in Phoenix House, Charing Cross Road, was for many years his home, office, editing room and studio – and how many people flowed in and out of it – half of London it seemed sometimes! Anyone he felt was an ally was welcome, and there was always tea and conversation about politics, about a film he’d just seen (I remember him enthusing about Josef Von Sternberg and Mad Max), about raising money and his current projects. If you were broke and he still had some overdraft left, he took you for lunch in one of the cheaper Italian places in Soho he’d made his extended home. He was an exceptionally generous man, lived in just the clothes on his back.

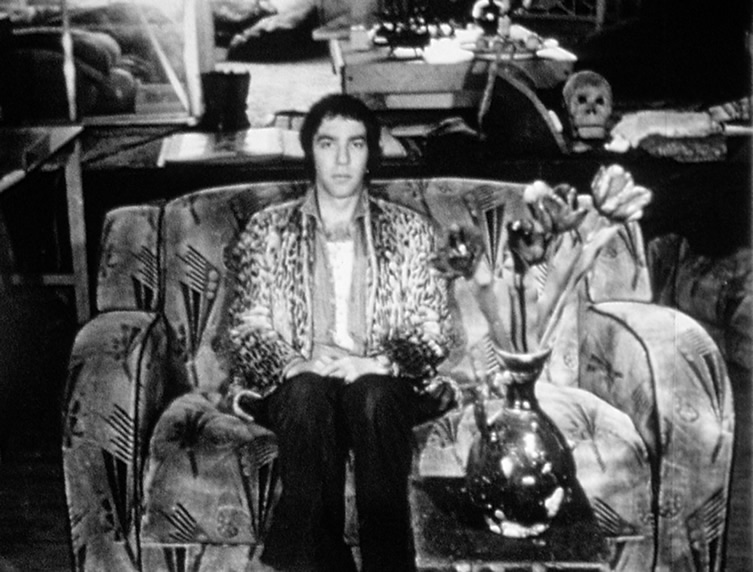

When I first knew him he lived at Butler’s Wharf in a big studio space, cheap then to rent. (Pictured, left: Studio Bankside, Derek Jarman, 1973-74, © LUMA Foundation). When an important location fell through for Nighthawks at the last minute, because the owner suddenly feared for the safety of all her artworks with a film crew and 20 extras trudging through her Victorian mansion apartment, Derek offered us his studio, gave us the keys and went out for the night. He had already appeared briefly in the club scenes in the film and was enthusiastically tracking our progress, helping us in all kinds of small ways all through. The producer Don Boyd recalls Derek arguing for the film at a very early stage and that itself led to meetings with Don and his support as one of several producer-financiers who made that film possible.

When I first knew him he lived at Butler’s Wharf in a big studio space, cheap then to rent. (Pictured, left: Studio Bankside, Derek Jarman, 1973-74, © LUMA Foundation). When an important location fell through for Nighthawks at the last minute, because the owner suddenly feared for the safety of all her artworks with a film crew and 20 extras trudging through her Victorian mansion apartment, Derek offered us his studio, gave us the keys and went out for the night. He had already appeared briefly in the club scenes in the film and was enthusiastically tracking our progress, helping us in all kinds of small ways all through. The producer Don Boyd recalls Derek arguing for the film at a very early stage and that itself led to meetings with Don and his support as one of several producer-financiers who made that film possible.

I saw Derek a lot in those days and was remembering the other day how often we talked on the phone. Once he called me to ask if I had seen that day’s Sunday Times. I hadn’t. He told me to go out and buy it as we were both part of the main story on the front page of the Arts Section, attacked, alongside several other filmmakers, for making films that were unpatriotic. The writer was Norman Stone, then an adviser to Margaret Thatcher, and The Last of England and Empire State were two films of six that had raised his blood pressure to bursting point.

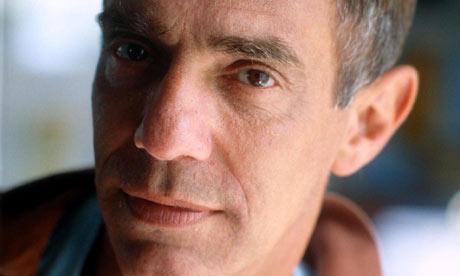

It is Derek’s voice I especially recall. (I find this is so with all the friends who have died: their voices never leave me.) I can hear Derek speaking now as if he was here, talking across the room. His voice was certainly a little posh, which at first intimidated me a bit, but God was it full of feeling! Both his enthusiasm and anger knew no bounds. That little room in Phoenix House was his stage. The first image that comes to mind in remembering Derek is him pacing up and down, raging at the BFI, C4, the ACTT or the government (“Fuck the lot of them!”), after another rejection or delay in production finance. The years of struggling to make Caravaggio (pictured below) particularly took their toll. He’d proven himself before with three feature films and yet he was still treated as if he’d never made anything. These were days when even for him it was hard to hold on to those initial impulses that led him to dream up the film in the first place.

He had, luckily, strong and regular collaborators, who were also his very close friends, Christopher Hobbs and James Mackay especially in his most independent work, Sarah Radclyffe in the bigger budget films. Though I’m sure he was fiery to work with, of necessity, I remember that he spoke with real affection and feeling about all of these people and also the wider circle of crew and performers. Tilda Swinton I met just a few times but to everyone looking on it was obvious they somehow inspired each other in a very special way, dared each other on, kept the flames of inspiration burning.

He had, luckily, strong and regular collaborators, who were also his very close friends, Christopher Hobbs and James Mackay especially in his most independent work, Sarah Radclyffe in the bigger budget films. Though I’m sure he was fiery to work with, of necessity, I remember that he spoke with real affection and feeling about all of these people and also the wider circle of crew and performers. Tilda Swinton I met just a few times but to everyone looking on it was obvious they somehow inspired each other in a very special way, dared each other on, kept the flames of inspiration burning.

In the later years I saw him less than before. We were both trying to make films and it had never really got easier and the effort consumed more and more of our time. His own time was especially precious in those later years and he urgently needed to keep on making things, to somehow say new things, to target his indictments precisely, yet to still remind us of wonderful things that existed in this world.

In 1984 he produced a kind of manifesto and asked a number of us to help him distribute it in protest at the travesty of British Film Year and a new book on British cinema, James Parks’ Learning to Dream, at a rather pompous event at the ICA. In it he asked for a small space in which independents could work – “independent” was the recurring word in his manifesto and meant everything then, just as it means almost nothing now.

That “small space” was never ceded by finance but was to some extent created instead through alternative technologies. That Super-8mm camera in the glass case had seen exceptionally active service over very many years. Derek recorded much of his earlier life with it. Later, Super-8 became a different kind of Godsend, a way to make feature films without any money. Almost magically, Derek and James Mackay conjured up films that went mysteriously from film to video to film again and somehow ended up as 35mm films with Dolby sound in big screen cinemas. I went with my collaborator on Empire State, Mark Ayres, to see The Last of England (pictured, above right) at the Scala Cinema in Kings Cross and was genuinely shaken. I was sure my hair had literally stood on end. Yet that film had originated from this tiny Super-8mm camera.

That “small space” was never ceded by finance but was to some extent created instead through alternative technologies. That Super-8mm camera in the glass case had seen exceptionally active service over very many years. Derek recorded much of his earlier life with it. Later, Super-8 became a different kind of Godsend, a way to make feature films without any money. Almost magically, Derek and James Mackay conjured up films that went mysteriously from film to video to film again and somehow ended up as 35mm films with Dolby sound in big screen cinemas. I went with my collaborator on Empire State, Mark Ayres, to see The Last of England (pictured, above right) at the Scala Cinema in Kings Cross and was genuinely shaken. I was sure my hair had literally stood on end. Yet that film had originated from this tiny Super-8mm camera.

Derek also embraced the liberating possibilities of the first relatively inexpensive video cameras – the Olympus VHS camera particularly excited him. He encouraged me to buy one as another means to circumvent the vested financial and institutional interests that owned British cinema. You no longer needed 35mm or even 16mm or Super-16mm. You could now make films without seeking the permission of government institutions, banks and TV broadcasters. How he would have relished the current technologies! He would, I think, have never stopped filming with his phone. He would have become a guerrilla fighter, firing from a hundred places at once. The old UK Film Council would have fallen on its knees from all his arrows.

Have I conveyed – a little at least – the energy and excitement and enthusiasm and fierceness of this very great man, as well as a certain disquiet about his capture by academia? I hope so, for this great wild beast of cinema should always have evaded being netted and caught. By all means we should all pay homage and visit the glass cases at Somerset House as we might go to the British Museum and look at the mummies and the Greek vases. It is not un-useful. But Derek isn’t there. He’s in his films, his books, his artworks, in the recordings of that exceptionally lucid and articulate voice. It’s these that keep us connected to those four elements that made up Derek, make up you and I and this giddying, still surprising and still often blazingly beautiful world that Derek so wanted us to see and feel and act upon.

Overleaf: the story of Derek Jarman's Will You Dance With Me? which premieres at the BFI Southbank on March 22

Unseen Jarman: Will You Dance With Me?

In 1984 I started work on a new film called Empire State, beginning, as I often prefer to do, not with a script but with non-professional actors who had a stake in the subject matter generating material through an improvisation acting workshop. Importantly, that work was always developed in relation to a camera. This was from the beginning conceived as cinema, not as theatre recorded on videotape.

In 1984 I started work on a new film called Empire State, beginning, as I often prefer to do, not with a script but with non-professional actors who had a stake in the subject matter generating material through an improvisation acting workshop. Importantly, that work was always developed in relation to a camera. This was from the beginning conceived as cinema, not as theatre recorded on videotape.

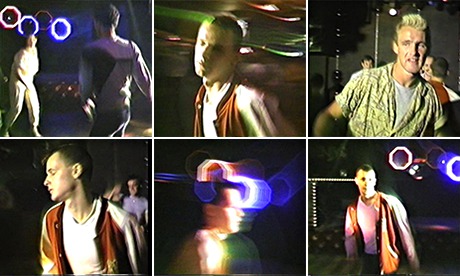

Some of the most ambitious early tests were shot at Benjy’s, an East London nightclub in Mile End. One night about a hundred people were invited to participate, including club regulars I’d got to know there (it was my local), the regular bar staff, and people being considered for specific roles in the film. There were two cameras recording in different parts of the club that night and one of these was operated by Derek Jarman.

an intensely moving experience – as a record of that evening’s genuinely free experimenting

The tape that Derek shot is the only one that has survived. I invited him to join us in trying to “find” this film and asked him to do two things: to catch something of the fluidity of movement in the club in the course of the night and to record dancing as a “release” from the social tensions that would be expressed elsewhere in the film – and to record dance in as exciting, explosive and participatory a way as he could.

The tape was viewed, assessed and then put away in a cupboard for almost 30 years. Our initial enthusiastic, even anarchic approach was refused finance everywhere. Although the film was made three years later, it was much more on mainstream cinema lines – not in these bar locations but in a studio reconstruction, not for the most part with the original street kids, but with professional actors, not improvising but working from a fully written script. That was the only way we were allowed to make it.

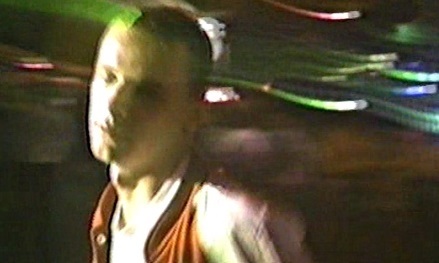

Looking again recently at the VHS tape Derek shot, I found it an intensely moving experience – as a record of that evening’s genuinely free experimenting, as a record too of another time and place now gone, but also as an insight into Derek’s own filmic approach, his own mind and eye shaping images and somehow creating his own narrative within our emerging Empire State narrative. His camera not only caught the rhythms of people’s movements but was an active and roving participant itself. Time and again he returns to the dance floor seeking a way to best catch the rhythms of people dancing, by joining in. He succeeded, I believe, in creating some of the best images of dance I have ever seen anywhere, images which involve the camera – which means Derek – itself. (Pictured, above right, and in main picture: Philip Williamson, one of the main actors in Derek Jarman's The Angelic Conversation, who also worked on the final production of Empire State).

Looking again recently at the VHS tape Derek shot, I found it an intensely moving experience – as a record of that evening’s genuinely free experimenting, as a record too of another time and place now gone, but also as an insight into Derek’s own filmic approach, his own mind and eye shaping images and somehow creating his own narrative within our emerging Empire State narrative. His camera not only caught the rhythms of people’s movements but was an active and roving participant itself. Time and again he returns to the dance floor seeking a way to best catch the rhythms of people dancing, by joining in. He succeeded, I believe, in creating some of the best images of dance I have ever seen anywhere, images which involve the camera – which means Derek – itself. (Pictured, above right, and in main picture: Philip Williamson, one of the main actors in Derek Jarman's The Angelic Conversation, who also worked on the final production of Empire State).

The 78 minutes of unedited raw material that Derek shot will be shown at BFI Southbank on March 22 and it should soon be widely available for anyone to see. Being originally just part of the experimental development work-in-progress for Empire State, it of course never had a title. I came up with Will You Dance With Me? which Derek asks one of the people he is filming early on. By the end of the tape he is dancing not just with this particular man but with the whole club. The result is exhilarating, joyous and visually very exciting indeed and is not like anything else I ever saw Derek shoot. I never saw him so happy.

© Ron Peck, 2014

Add comment