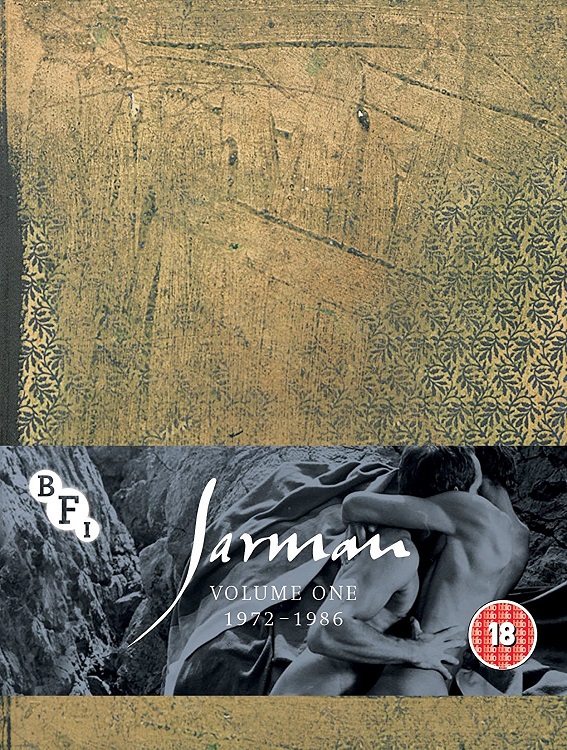

This BFI boxset of Derek Jarman films from the first phase of his career, brilliantly curated by William Fowler, is an exemplary package: a treasure trove of extras accompanies his first six features, here presented in re-mastered form, and a thorough, well-illustrated and thought-provoking 80-page booklet with extensive material about the films and a wealth of essays.

The collection makes it possible to follow the evolution of Jarman as a film-maker, always riding the wave of creative and mould-breaking adventure, from the mysteries of In the Shadow of the Sun (1981), a film that built on much of Jarman's super-8mm footage from the 1970s, the controversial Sebastiane (1976), through to the explosive punk-inspired politics of Jubilee (1978), followed by The Tempest (1979), surely one of the best adaptations of Shakespeare on film, the avant-garde rigour and homo-erotic delirium of The Angelic Conversation (1985), and the assured and more straightforward account of the rebellious life of the painter Caravaggio.

The extras draw extensively on Jarman’s early super 8mm films – all of which prefigure his later work, a film-making career that was at times erratic and sometimes undermined by Dionysiac excess, yet displays a remarkable integrity and continuity of poetic imagery. In the 1970s, he had plunged into the alchemical writings of CG Jung, work that gave him confidence to follow the imagery that had already featured extensively in his own dreams. Films such as Journey to Avebury (1971) and Art of Mirrors (1973) feature images that recur in later films, not least the bright flares carried aloft and mirrors which "blind" the eye of the camera and wreak havoc with automatic exposure.

The extras draw extensively on Jarman’s early super 8mm films – all of which prefigure his later work, a film-making career that was at times erratic and sometimes undermined by Dionysiac excess, yet displays a remarkable integrity and continuity of poetic imagery. In the 1970s, he had plunged into the alchemical writings of CG Jung, work that gave him confidence to follow the imagery that had already featured extensively in his own dreams. Films such as Journey to Avebury (1971) and Art of Mirrors (1973) feature images that recur in later films, not least the bright flares carried aloft and mirrors which "blind" the eye of the camera and wreak havoc with automatic exposure.

There are also many interviews with collaborators and actors, from designer Christopher Hobbs, producer Don Boyd, artist and film-maker John Scarlett-Davis and actor Nigel Terry (excellent as Caravaggio), to Jarman’s muse Tilda Swinton and Jordan, one of the stars of Jubilee. Several remember vividly the atmosphere that Jarman was able to conjure on set, and reflect on the fact that the convivial process of the making of the films was perhaps more important than the finished product. Derek Jarman fizzed with energy and was able to infect those around him with the same almost child-like passion for play and the breaking of taboos and boundaries. He was both a fierce traditionalist, in love with a mythic sense of England, and a rebel, fired by a fury at what he saw as the failings of the world, a world that fell short of his dreams of artistic freedom, the freedom afforded by dreams, and a lifestyle nourished by the possibility of transgression.

The importance of process is crucial in understanding Jarman’s work. His genius lay more in creating an atmosphere and inspiring others, and the effervescence and extraordinary range of his work – as a painter, set-designer, writer, film-maker and activist – than in any of his single works, most of which were flawed. He was as much of a magus, as the boxset’s curator William Fowler writes in the booklet, for whom film-making was a form of collective ritual: Tilda Swinton speaks of a “Sisyphean task”, a form of sympathetic magic, designed to change the world.

Jarman was in any case more of a visual artist than a story-teller, and films like The Angelic Conversation, however mesmeric in their use of repetition, with elemental symbols such as earth, water and fire, belong more to the art gallery than the cinema. The disjointed nature of Sebastiane could pass as an attempt to undermine the linear tropes of conventional narrative, but the clumsiness of the film’s dramatic structure works against its undeniable beauty.

Jarman’s work was fuelled by anger, a passion which at times worked against the strength of his films. Jubilee has its moments, and is at times simply extraordinary – as when Jordan sings and dances her way through a punkish “Rule Britannia” – but the film rambles on, failing to build any real tension. This is perhaps because of the essentially anti-narrative and Dada roots of punk, but the relentless shock and awe, in this anti-celebration of Queen Elizabeth II, tires after a while, though it is miraculously rescued by the magical sequences where the first Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by the magus John Dee, wanders through 1970s England, and at the lyrical and nostagic end of the film, made all the more magical by the soft and entrancing voice of actor Richard O'Brien as Dee, along the Dorset shoreline of Dancing Ledge, a place both sacred and dear to Jarman.

Jarman’s inner world and self-image are omnipresent in all these films – whether as the rebel painter Caravaggio, forced to make artistic compromises with a corrupt Pope, or the magician Prospero in The Tempest. He chose characters that mirrored aspects of himself – female, as with Amyl Nitrate in Jubilee, or masculine such as the martyr Sebastiane. The theme of martyrdom was dear to him – there are recurring images of young men suffering under the weight of heavy oil drums and wooden beams, which they carry on their shoulders, through a barren rocky landscape – and resonated well with his chosen role as gay revolutionary.

The Tempest is without doubt the best of the films in the set, though Caravaggio comes a close second, perhaps the closest he ever came to making a masterpiece. In the first, the brilliant dramatic core of Shakespeare’s text serves him well, though there is also the presence of Heathcote Williams – not just on screen, but also as a collaborator: an ideal casting, as well as an expression of Jarman’s desire to be a magician capable of conjuring the world around him. The exploration of power – both political and alchemical – was central to Jarman’s quest and this extraordinary play evokes most potently the way in which the imagination can make the world, in a way that one of Jarman’s mentors, the post-Jungian writer James Hillman, whose books the artist and film-maker cherished, very well understood.

With an abundance of fascinating interviews, which could have done perhaps with a little more editing, and other extras, this boxset will delight Jarman fans and completists as much as those who want to explore in some depth the cinematic oeuvre of a particularly English artist, a Renaissance man with his heart and head in tune with the pulse of his time. He belongs to a glorious tradition of spiritually inspired and politically angry anti-conformism that is unique to Britain, one that thrives on a kind of nostalgia, and yet seeks to continuously break new ground.

Add comment