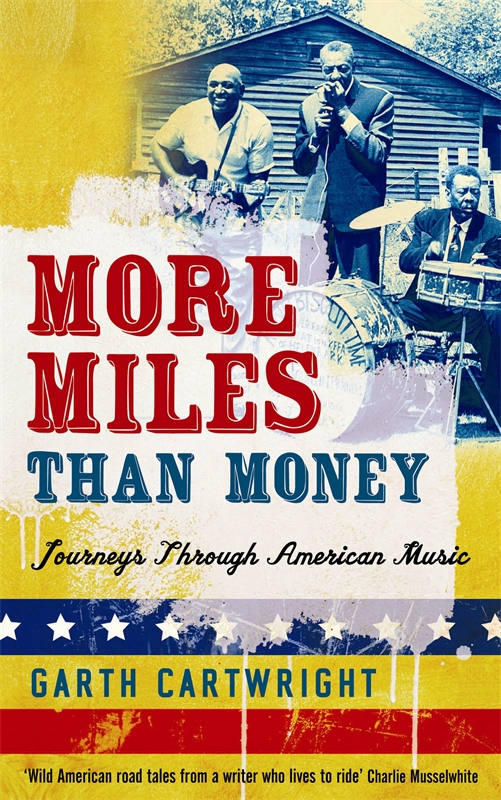

Inevitably, reading Kerouac ruined me. Not that I headed to the US expecting things to be as they were in Jack’s time. Yet just how harsh poor America can be to live and travel amongst did surprise me. The title of More Miles than Money: Journeys through American Music is from an Alejandro Escovedo song about the musician’s life, but it fitted not just the people I was meeting but also how I travelled. So many miles to cross. And so little money. It became a quest with rules: avoid famous artists, seek out visionaries and lost legends, ride Greyhound, no phone interviews or running to Holiday Inn – stay on the Rez, in the barrio, engage.

Inevitably, reading Kerouac ruined me. Not that I headed to the US expecting things to be as they were in Jack’s time. Yet just how harsh poor America can be to live and travel amongst did surprise me. The title of More Miles than Money: Journeys through American Music is from an Alejandro Escovedo song about the musician’s life, but it fitted not just the people I was meeting but also how I travelled. So many miles to cross. And so little money. It became a quest with rules: avoid famous artists, seek out visionaries and lost legends, ride Greyhound, no phone interviews or running to Holiday Inn – stay on the Rez, in the barrio, engage.

I wanted to hear music in the communities where it was created: powwows on the Navajo Nation, blues in Mississippi juke joints, country in Texan honky-tonks and mariachis in San Antonio bars. And to hear the musicians’ stories, why they sang, how America shaped them. So More Miles than Money is my own American dream, a journey in stories and songs. The following extract is from a chapter entitled “Not in Raceriotland . . .”

South Central LA bleeds warehouses, strip clubs (“To our customers: lock your cars and take your keys”), wreckers yards (“We Buy Junk Cars”), fast food joints, gas stations, tyre merchants, railway lines, omnipresent striped taco stands, shabby factories, faceless office blocks. Flat, dusty, tense, inimical - the LA of Point Blank and Reservoir Dogs - hermetic environs, designed to isolate, keep paranoia levels high, conduct near invisible business. Grid roads, telephone cables, traffic lights, city gristle. Those resident here are constantly reminded just how fugacious their existence can be.

Out of East LA we’d cruise down Alameda, Luis noting where working-class white, black and brown communities once existed, divided by race and railway tracks. Back in the day South Central’s workforce filled local mills and factories. “LA had the second largest industrial base in the US after Chicago,” says Luis, “huge steel mills like you wouldn’t believe. I worked in them in the Seventies, doing pipe-fitting, carpentry, lots of stuff. The racial tension from the streets carried into the factories but, for the most part, people got on. Now, well, almost all of the heavy industry has gone. The owners shifted the work to Mexico or China.”

The 1965 Watts Uprising encouraged white flight – “cops told the whites blacks were coming for them so people were standing on their front lawns with shotguns” – followed by an exodus of black residents who could afford to shift. South Central’s now becoming a barrio for new arrivals from Mexico and Central America. This being evident at our intersection: moving among traffic a girl (maybe 12) begs; one man sells oranges, another soft toys.

We drive on and at the next intersection there’s coconuts and flowers for sale. “Imagine leaving your home town,” I say, “crossing the desert, going through all those extremes to enter the US and finding that the better life you dreamed of involves standing at these lights all day.” Luis mentions how the US-Mexico free trade agreement brokered by Clinton screwed Mexican farmers, dumping cheap maize on Mexico, forcing a wave of landless farmers north. “LA’s a tough place to survive in and getting tougher. The way the system is now, it’s much more difficult than when my family arrived. That’s one of the reasons gangs thrive: they offer security, a sense of belonging, to a lot of displaced people.”

As Luis turns into Slauson Avenue he recalls the Slausons, a black gang of the 1950s and ‘60s. We pass a McDonalds with Spanish signs, bungalows with barbed-wire fences and pit bulls behind them, concrete walls with broken glass embedded, droopy palm trees and youths with shaven heads and baseball shirts. A police helicopter floats overhead. We turn left and Luis says, “Central Avenue.” “Well,” I say, “all right.”

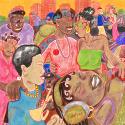

Yet “all right” isn’t the correct expression. For Central Avenue (picture left), which connects Downtown with Watts, looks anything but all right. A Jack-In-The-Box trash food emporium, Nails outlets, 99c shops, empty lots, Louisiana Fried Chicken, a caged Chinese food vendor, Central Liquor Bank, Kick-Boxing, Missionary Baptist Church. Central Avenue resembles East LA in its strip-mall shoddiness but it’s poorer, more threadbare. And yet Central Avenue once provided LA’s musical heartbeat, comparable to Harlem, packed with clubs and juke joints pumping jazz and blues. Jelly Roll Morton, self-styled “inventor of jazz”, played and recorded here in 1918 while it was here that Jack Johnson ran Club Alabam in 1932. Kerouac turned up in 1947, breathlessly enthusing about “the wild, humming night... chickenshacks barely big enough to house a jukebox, and the jukebox blowing nothing but blues, bop, and jump”. The presence of famous white LA citizens mixing with the locals at clubs on Central Avenue infuriated Chief Parker, then the LAPD’s ruling bully. Through citing “interracial vice”, Parker viciously succeeded in snuffing out much of LA’s jazz/blues scene by the mid-1950s.

Yet “all right” isn’t the correct expression. For Central Avenue (picture left), which connects Downtown with Watts, looks anything but all right. A Jack-In-The-Box trash food emporium, Nails outlets, 99c shops, empty lots, Louisiana Fried Chicken, a caged Chinese food vendor, Central Liquor Bank, Kick-Boxing, Missionary Baptist Church. Central Avenue resembles East LA in its strip-mall shoddiness but it’s poorer, more threadbare. And yet Central Avenue once provided LA’s musical heartbeat, comparable to Harlem, packed with clubs and juke joints pumping jazz and blues. Jelly Roll Morton, self-styled “inventor of jazz”, played and recorded here in 1918 while it was here that Jack Johnson ran Club Alabam in 1932. Kerouac turned up in 1947, breathlessly enthusing about “the wild, humming night... chickenshacks barely big enough to house a jukebox, and the jukebox blowing nothing but blues, bop, and jump”. The presence of famous white LA citizens mixing with the locals at clubs on Central Avenue infuriated Chief Parker, then the LAPD’s ruling bully. Through citing “interracial vice”, Parker viciously succeeded in snuffing out much of LA’s jazz/blues scene by the mid-1950s.

Parker’s LAPD viewed blacks and Chicanos as a criminal class so policed South Central with a brutality that, when twinned with the discriminatory hiring policies employed by LA’s construction, aerospace and entertainment industries, lit a racial powder keg: on August 11, 1965, Watts exploded into a week of violence and arson leaving 34 dead, 1,100 injured, 4,000 arrested, 600 buildings damaged or destroyed. Several miles north LA’s psychedelic era took shape around Hollywood yet beyond Frank Zappa’s riot-referencing "Trouble Every Day on Freak Out" little attention was paid; to pop’s pampered elite Watts was as distant as Morocco, if not quite so romantic.

The riots lead Thomas Pynchon to travel, almost a year later, into South Central and write the rambling, if illuminating, A Journey into the Mind of Watts for The New York Times Magazine (June 12, 1966). Pynchon’s fiction is unfathomably dense and hubristic yet his essay is unfussy, stumbling only when he romanticises ghetto dwellers like so much rock/rap journalism: “Everything seems so out in the open, all of it is real, no plastic faces, not transistors, no hidden Muzak, or Disneyfied landscaping, or smiling little chicks to show you around. Not in Raceriotland... These kids are so tough you can pull slivers of it (glass) out of them and never get a whimper.”

The surrounding urban landscape mixes those L.A. totems of scruffy palm trees with off kilter suburban ruination: Chief Parker, his successor Daryl Gates, and the '92 riots have all left a lasting imprint. In the late afternoon heat a sense of subjection hangs across the ‘hood. Little of LA’s fabulous wealth and fantasy trickles down to Watts: the community has the lowest household income in all of Los Angeles County at $17,987 with 49.7 per cent of families and 49.1 per cent of individuals below the federal poverty line. Sociologist Carl Taylor has coined the phrase “Third City” to describe places like Watts, places abandoned by mainstream America, places heavy industry has left so bequeathing high unemployment and low expectation, declining public services and spiralling crime rates, the drug trade now an economic mainstay, crack cocaine and automatic weapons terrorising the community. “A lot of this area burned during the 92 riots,” says Luis, “and there’s been little reinvestment. My brother worked for a phone company and was down here when the city went off. He had to hide in his work for three or four days. Couldn’t go home. Fires everywhere. Gangs rampaging.’

We turn off Central Avenue and roll along 109th St until we pull up in front of Watts Towers (pictured right). It’s an odd construction, folk art of sorts, built by Simon Rodia between 1921 and 1954. He laboured alone, paying for this baby Gaudi edifice from his wages as a window cleaner, using scrap pottery, glass, rocks, sea shells, all kinds of colourful refuse, alongside cement and iron, to create a taste of urban magic. The Watts Towers are enclosed behind a fence now, recognised as a genuine LA artefact, but Luis recalls a childhood where The Towers were a playground.

We turn off Central Avenue and roll along 109th St until we pull up in front of Watts Towers (pictured right). It’s an odd construction, folk art of sorts, built by Simon Rodia between 1921 and 1954. He laboured alone, paying for this baby Gaudi edifice from his wages as a window cleaner, using scrap pottery, glass, rocks, sea shells, all kinds of colourful refuse, alongside cement and iron, to create a taste of urban magic. The Watts Towers are enclosed behind a fence now, recognised as a genuine LA artefact, but Luis recalls a childhood where The Towers were a playground.

“We used to climb this thing. It’s amazing it hasn’t fallen apart. Rodia was a little guy, only five foot tall, but a real visionary. I always found it inspiring that he built the Towers for no practical purpose, just out of creative spirit."

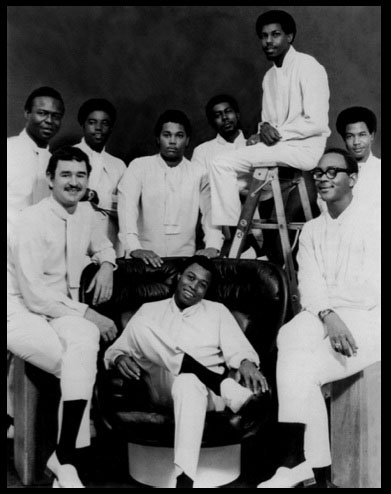

In front of the Towers black marble plaques honouring Watts’s finest. I recognise critic Stanley Crouch, athlete Florence Griffith Joyner and a whole host of musicians: Aaron “T-Bone” Walker, Charlie Mingus, Johnny Otis, Eric Dolphy, Esther Phillips, Etta James and the man who truly put his ‘hood on the musical map - Charles Wright, leader of the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band. I mention my love for Charles Wright’s music and Luis nods ascent.

"Back in the day any low-rider with style would blast Charles Wright. That was hard core LA street music."

Charles Wright is more than just a local hero. His musical legacy links Delta blues with soul, doo-wop to hip-hop. Underlying Wright’s finest music is the essence of funk: African-American groove, pride, sensuality, earthiness, an aesthetic seemingly derived from the Ki-Kongo word “lu-fuki”, suggesting both bad body odour and artistic achievement, an expression employed by black musicians in New Orleans since the 19th century. Funk, in the music of Wright and James Brown, establishes a raw sonic beauty. Seeing Wright’s name in Watts stone made me want to meet him and Luis, of course, knew where to find Charles.

Charles Wright is more than just a local hero. His musical legacy links Delta blues with soul, doo-wop to hip-hop. Underlying Wright’s finest music is the essence of funk: African-American groove, pride, sensuality, earthiness, an aesthetic seemingly derived from the Ki-Kongo word “lu-fuki”, suggesting both bad body odour and artistic achievement, an expression employed by black musicians in New Orleans since the 19th century. Funk, in the music of Wright and James Brown, establishes a raw sonic beauty. Seeing Wright’s name in Watts stone made me want to meet him and Luis, of course, knew where to find Charles.

Aged 65, Wright now lives in a spacious house in Orange County. Upon arrival I find him leading a band rehearsal. Across the afternoon Wright directs the band and, during breaks, answers my questions. He speaks with unshakeable conviction, his rasping voice and granite features speaking of hard scrabble, determination, a refusal to flinch. “Most of the neighbours are Korean,” he says when I ask about this ‘burb. “They ain’t too friendly but they don’t cause no problems either.” His house is a long way from the sharecropper’s shack he was born intoor the small Watts bungalow he and his 15-member family shifted into in 1950, Wright’s hard won musical success having ensured him a degree of comfort.

"I was born nine miles outside of Clarksdale, Mississippi, on a cotton patch. My father was a sharecropper. I spent my first ten years in that shack. They call it sharecropping, I call it slavery. The way we were living down there at that time... My dad insisted I pick 100 pounds of cotton a day. I couldn’t do it. I’d get 92, 94, 98 pounds. But I couldn’t get 100. Each time I didn’t get to 100 he whupped me. Reason I say it was slavery is each time at the end of the year a sharecropper would have to settle with the guy who owned the land and my father always ended up in the hole. No matter how hard he pushed us, how hard we worked, how hard he tried not to buy materials from the man, he always ended up owing the man money. Each year at a certain time of year he’d come in the house with a look on his face and my mother would say, ‘He gotcha again, didn’t he?’

“When I was 10 we moved into Clarksdale but the guy we used to do the sharecropping for was trying to force us back - he had connections with the police - so we shipped out. LA was like day and night. I’d been in Clarksdale but I’d never really been in a city. Los Angeles was huge. I had to catch on quick but you can’t believe what a change LA was to Mississippi. My family settled in South Central Los Angeles. It was all kinds of ethnic groups living together. Whites, Japanese, Mexicans and blacks, we all got on. Integrated schools. And my parents could buy a lot of food for their money. Today it’s not a good city to live in and your money buys nothing. Ronald Reagan got elected Governor in 1966 and he ruined the state. Then he got elected President and he ruined the country.”

Wright’s importance to LA’s black music scene is undeniable: his slangy, drawling sing-rap delivery, loose, spiralling guitar-playing, hip street philosophy and raw, under-rehearsed sound gave black LA its groove back after Central Avenue’s cessation. He opened doors for the likes of Barry White (his drummer in the Sixties) and War, the superb South Central funk-Latin-blues ensemble.

“Everybody wanted me to play on their records and so I did that from ‘65 through about ‘67. Played on a lot of hit records – Bettye Swann, Leon Hayward, Dyke and the Blazers. I was in the studio all day and with the band all night. It was a great trip. Warners signed us on Bill Cosby’s advice. They were looking to get into the R&B scene and they began to see us as the way to that market.”

Whether preaching soulfully on “Comment (If All Men Are Truly Brothers)” or drawling ‘bout Good Things over a spacey, minimalist groove, Wright’s music is constantly full of surprises: rhythms tug, guitars go to interesting places. It’s talking drum music, African music made in America.

“I created my own rhythms and stuff. I tried to be different but effective. I admired James Brown and Otis Redding, would do a lot of their stuff in the clubs. James Brown usually played only two or three changes in a song. I brought in more chords, more arrangement. Sometimes we would find a rhythm and work up a song from that. ‘Express Yourself’ came out of me improvising over the end of ‘Do Your Thing in Texas’ and the kids goin’ crazy for it.”

“I created my own rhythms and stuff. I tried to be different but effective. I admired James Brown and Otis Redding, would do a lot of their stuff in the clubs. James Brown usually played only two or three changes in a song. I brought in more chords, more arrangement. Sometimes we would find a rhythm and work up a song from that. ‘Express Yourself’ came out of me improvising over the end of ‘Do Your Thing in Texas’ and the kids goin’ crazy for it.”

He then adds, “They rarely play us on LA radio. Black radio don’t play us now and oldies stations don’t play us like they do the other groups. See, Watts is still getting blamed for the ‘65 riots and so we take that blame by not getting played."

What are Wright’s recollections of the riots?

“I don’t know, being the first people on the block to start a riot, people don’t like that. If another policeman had stopped me and felt my balls I would have really lost it. So I got out. I could have participated but I didn’t. I don’t think people really wanted to riot but enough is enough – it was an emotional outburst. We’d been backed up as far as we could go. Our humanity had had enough. ‘Cos the LA police and sheriff’s department, their job was to keep us in our place and they loved to do that. I always heard they recruited from Southern whites and those people had a mean attitude. So it was a hot night and it happened. And what happened in LA and what happened in Detroit, they were gonna happen. ‘92? That was what I call a fair riot. ‘Cos we knew those guys beat Rodney King to a pulp. That was a non-racial riot, lots of Latinos and blacks involved."

Wright pauses, thinks about what he’s said, then adds, “Personally, I would love to see people sit down and talk rather than go to war with one another.”

More Miles than Money: Journeys through American Music by Garth Cartwright (Serpent’s Tail). Buy the book here. Visit the author's website.

Add comment