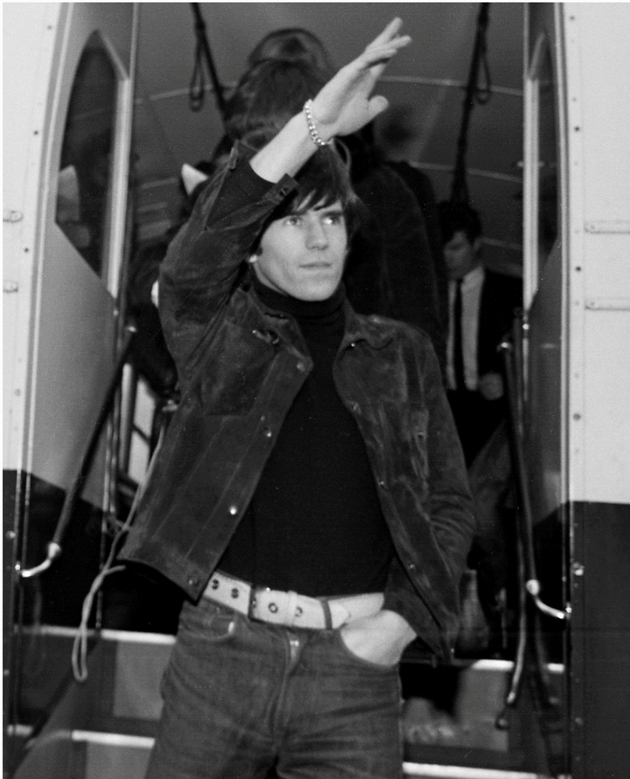

There’s a shot of the six of them running across a railway line in Belfast, running for their lives, Brian Jones at the rear, "Satisfaction" at the top of the charts, and there he is, the one who set light to the whole thing, between Mick and Keith. For a time virtually a sixth member of the band, the teenage hustler-manager with the vision thing who walked into the Station Hotel in Richmond to see the Rollin’ Stones and said hello to the rest of his life, Andrew Loog Oldham is one of the few of his caste of Sixties svengalis to survive the ensuing five decades.

"Surely you’ve seen the blond in the tweed jacket picking his nose on the train from Belfast to Dublin?" Oldham told me back in 2004 when asked about his involvement in Charlie Is My Darling, the first and perhaps most intimate and unguarded of all the films about the Stones. We were talking via email as Oldham prepared to fly from his home in Bogota to the UK for a trio of Charlie screenings. Later, he invited me to lunch at Dolphin Square in Pimlico. I remember following him to the dining room, and the flourish with which he dealt with staff, with entrances and exits. You need charisma to do that, and Oldham had it in spades.

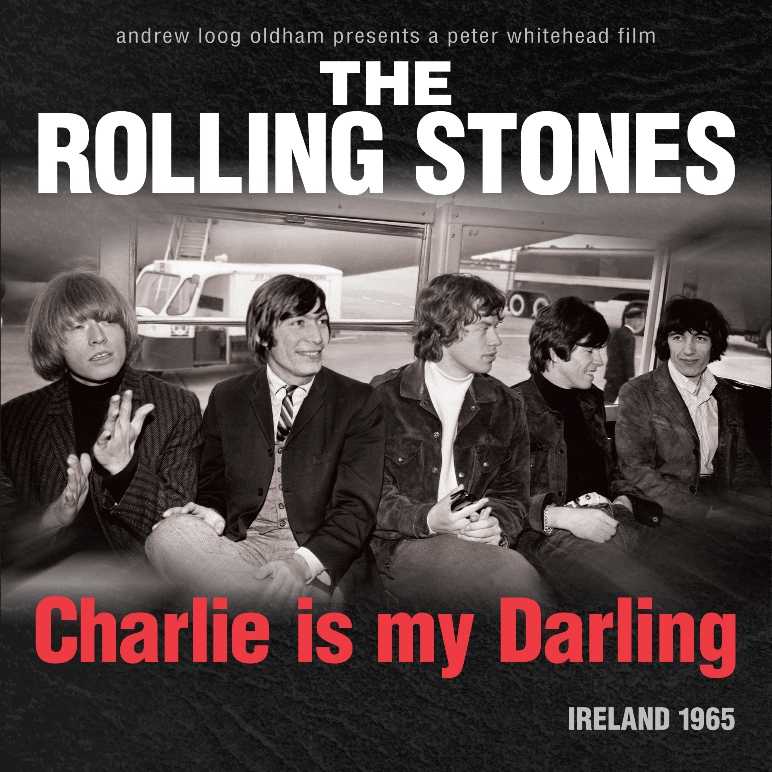

Almost a decade later - and 47 years after Oldham handed Wholly Communion film-maker Peter Whitehead £2,000 to film the band with one of the first-ever hand-held cameras - Charlie Is My Darling is finally getting its official release, out on DVD, CD and broadcast last night on BBC Two. Its sound and visual quality, after a lifetime of viewing in bootleg VHS format, is breathtaking.

Almost a decade later - and 47 years after Oldham handed Wholly Communion film-maker Peter Whitehead £2,000 to film the band with one of the first-ever hand-held cameras - Charlie Is My Darling is finally getting its official release, out on DVD, CD and broadcast last night on BBC Two. Its sound and visual quality, after a lifetime of viewing in bootleg VHS format, is breathtaking.

Shot over three days in Ireland in September 1965, it’s one of the first-ever road movies, and predating Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back, captures the Rolling Stones on the rollercoaster of Sixties pop stardom. The film’s stark verité style won high praise from Joseph von Sternberg at its first screening at the Mannheim Festival in 1966. "When all the other films at this festival are forgotten," he said, "this film will still be watched as a unique document of its time." Unique, and for decades almost impossible to get hold of. The only public showings came courtesy of Oldham with his one good VHS copy, which he carried with him to festivals.

"I made it to get the Stones in the mood, if that was possible," Oldham told me. "Charlie put up with a lot of prodding from Peter, and the interview is a classic. That's why the film is so titled. Keith gave an amazing vaudeville turn on a train at 10.30am, and Mick was good enough to shoot his myth in the foot with a delicious send-up of Elvis. Bill gave a very true and brave interview that explains musicians and the day," he concludes, "And Brian bravely boxed with himself." The doomed guitarist was already talking of the "insecurity of his future as a Rolling Stone".

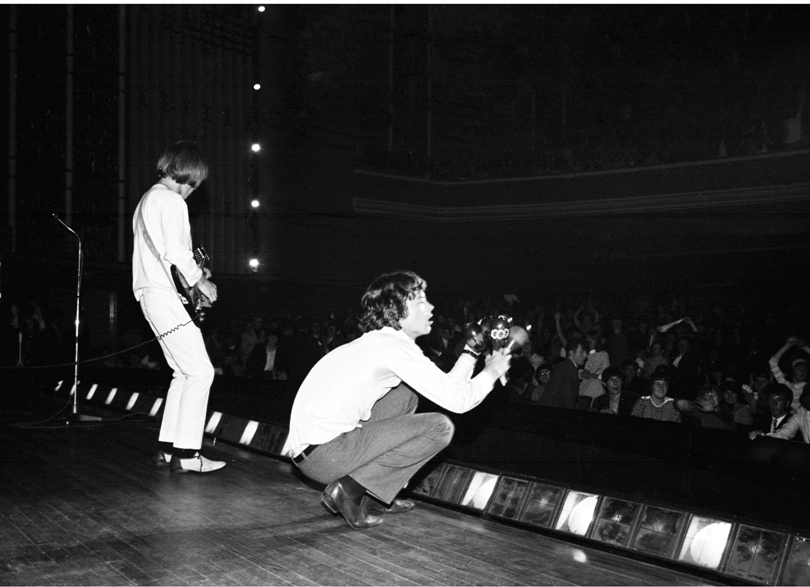

Edited by Whitehead, Oldham and the Stones themselves, the interviews are mixed with live footage that ends in a stage invasion, and scenes of the band on the train between gigs, on the run from fans, and at the piano in their hotel. "It’s not Help! or A Hard Days Night," Oldham said. "It's a demo - a few days in Ireland that captures the heart of the band at that moment." There’s Mick's Elvis impersonation, and Keith (pictured below) stirring the cauldron of yet-to-be-written songs, through his guitar or at the hotel piano. Jones slips in and out of focus. Charlie looks the most stoned, and Bill wears a dirty grin and never blinks.

Edited by Whitehead, Oldham and the Stones themselves, the interviews are mixed with live footage that ends in a stage invasion, and scenes of the band on the train between gigs, on the run from fans, and at the piano in their hotel. "It’s not Help! or A Hard Days Night," Oldham said. "It's a demo - a few days in Ireland that captures the heart of the band at that moment." There’s Mick's Elvis impersonation, and Keith (pictured below) stirring the cauldron of yet-to-be-written songs, through his guitar or at the hotel piano. Jones slips in and out of focus. Charlie looks the most stoned, and Bill wears a dirty grin and never blinks.

"The fuckin’ miracle of the opportunity," is how Oldham described the path the band followed in cutting their first ground-breaking singles, that had just taken them to the top of the charts with "Satisfaction" – the version on Charlie is one of its first concert performances, a thrilling, compacted strip of turbo-charged total rock 'n' roll. "Keith would come in with the flash and the rest would add the dash," Oldham said of the song-making. "Charlie had an inherent arranger’s mentality that shaped many an arrangement into being very, very special. We all know how good they all were - time just makes a point of it. We learnt on the job. We trusted our instincts, interest and ignorance - the three eyes, and wisdom itself for that short while."

"The fuckin’ miracle of the opportunity," is how Oldham described the path the band followed in cutting their first ground-breaking singles, that had just taken them to the top of the charts with "Satisfaction" – the version on Charlie is one of its first concert performances, a thrilling, compacted strip of turbo-charged total rock 'n' roll. "Keith would come in with the flash and the rest would add the dash," Oldham said of the song-making. "Charlie had an inherent arranger’s mentality that shaped many an arrangement into being very, very special. We all know how good they all were - time just makes a point of it. We learnt on the job. We trusted our instincts, interest and ignorance - the three eyes, and wisdom itself for that short while."

Out of all their peers, the Stones have remained alone in eschewing the middle-aged spread of radio sessions, outtakes, demos, and live tracks that have fattened the catalogues of virtually every other Sixties legend. But no longer. As the 50th anniversary rolls in with a new Best Of, a series of official, often stunning bootleg concert downloads in the online store, and their two biggest 1970s albums augmented with buffed-up extra tracks, Charlie Is My Darling – especially if you can afford the deluxe set with Glyn Johns’s mic-hung-over-the-balcony concert recordings - just might be the jewel in the crown.

Add comment