Horizon: The Hunt For AI, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

Horizon: The Hunt For AI, BBC Two

Horizon: The Hunt For AI, BBC Two

Through exploring artificial intelligence we learn what it is to be human

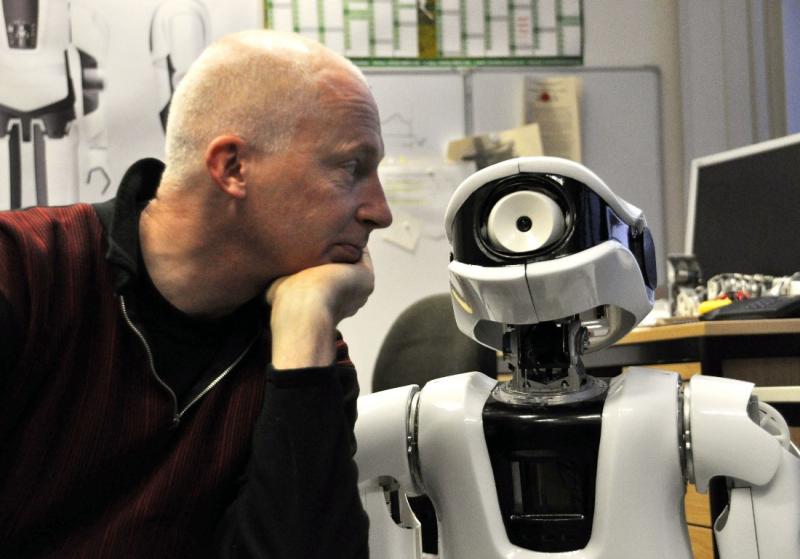

What is it with these scientists? Two spanking-new child-sized robots stand opposite each other in a room, talking. Their designer proclaims with barely concealed pride, “I don’t know which one is going to speak first.” In fact he says this twice, as if this very fact is proof that these bipedal assemblages are on the cusp, or have even reached some kind of sentient intelligence - rather than simply being mildly amazing, mildly amusing mimics of sentient intelligence.

OK, so they were speaking their own language which they'd created themselves, learning from each other as they went along. But for me this was no more impressive than an elaborate Derren Brown routine, in that it looked miraculous but was in fact just very, very clever. With films such as Terminator 2: Judgment Day in the back of one’s mind, it’s disconcerting to watch what could be the beginning of the rise of the machines. And last night’s Horizon certainly played on such celluloid-driven fears, as wide-eyed presenter Marcus du Sautoy ominously intoned questions such as, “What are these machines? Or who are they?”

Blue Gene could do in an hour what us mushy-brained primates would take half a lifetime to do

But another segment of the programme should have been enough to calm down even the most paranoid and pessimistic of sci-fi doom merchants. Blue Gene is one of the most powerful supercomputers in the world, yet it also looks like a throwback to an era when computers filled large rooms. Du Sautoy could barely hear himself interviewing its inventor, Fred Mintzer, so loud was the ocean roar of the cooling systems of its numerous filing-cabinet-sized racks of computational circuitry. It could do in an hour what us mushy-brained primates would take half a lifetime to do. And yet when Du Sautoy – displaying a healthy degree of scepticism for once – asked if it was “just an enormous number cruncher”, the answer was, sadly (or rather, thankfully), yes. Programmed intelligence is not artificial intelligence, even when it’s operating on such a colossal scale. In the simplest of layman’s terms: you only get out what you put in.

Another experiment effectively demonstrated that we’re still a lifetime away from having an AI-run Big Brother surveillance system. Computers can only “see” a tiny area of what’s on a CCTV monitor at any one time, continually scanning the screen in order to see the full picture. But then, of course, even if they could see the full picture they’d never get the full picture. Because to do so they’d have to bring into play intuition, suspicion, wariness, curiosity - to name just a few human characteristics that are useful when keeping on eye on hoodies skulking around shopping mals. For example, even the most sophisticated computer-driven surveillance system would not be able to tell if two drunken men were play-fighting or genuinely fighting.

Whatever name you give to the indefinable core of what it is to be human, it will always be an unachievable goal for AI

It wasn’t even the case that much new evidence was presented on last night’s Horizon to suggest we should be heading for the hills. How many times before – from Tomorrow’s World onwards – have we been told that humanoid robots can do their 6,789-times-table, and yet running, walking – or even just standing – is a real bugger? Or that they’re not much cop at art? Yes, good old robot art: it’s always amusing to see the nauseatingly soulless daubs that don’t even convince as bad graphic design. I wasn’t going to mention the soul, primarily because I doubt its existence. But documentaries on artificial intelligence bring out the hopeful agnostic in me, simply because they reaffirm just what a mysterious, marvellous and intangible thing human consciousness is.

I suspect that whatever name you give to the indefinable core of what it is to be human, it will always be an unachievable goal for AI. The fact is that, despite the admirable vision and wishful thinking of our most dedicated scientists, we are still a zillion miles away from an AI robot that could be considered as anything other than quite cute, a glorified children’s toy. How do you programme in curiosity, passion, excitement, imagination, joy?

By the end of this programme, Du Sautoy himself was willing to admit that true artificial intelligence was still a long way away. He also pointed out that perhaps trying to make AI machines imitate us is a false trail, which is something I'm in complete agreement about. But it’s been a false trail for half a century or more. We want to believe we can create friends and helpers out of silicone and plastic. In fact our urge to anthropomorphise is so strong that if Apple started sticking eyes on iPods, I think part of us would suspect them of having acquired independent thought. But then that's what makes us so wonderfully, stupidly human.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

Add comment