BBC Proms: Hodges, Bickley, Daniel, Britten Sinfonia, Rundell | reviews, news & interviews

BBC Proms: Hodges, Bickley, Daniel, Britten Sinfonia, Rundell

BBC Proms: Hodges, Bickley, Daniel, Britten Sinfonia, Rundell

Not conventional Saturday afternoon fun, but a bracing line-up of contemporary British music, powerfully performed

A motley crowd at Cadogan Hall on Saturday afternoon: new music aficionados and interested parties; general music lovers; some passing trade; tourists; one dad with a young boy of six or seven. Heaven knows what the latter made of the dissonances, dislocations and heated laments summoned forth by the intrepid performers in this invigorating concert, dominated by the creations of some of the more challenging composers among contemporary Brits.

It could be that the lad had a whale of a time, for a child’s sensibility might well respond to the exuberant anarchy of Michael Finnissy’s Piano Concerto No 2. Premiered in France in 1977, the work has taken 35 years to cross the Channel. Not that it’s aged a day. A permanent iconoclast, Finnissy uses a traditional title simply to smash conventions: the piece is basically a piano solo with muted contributions from strings and two alto flutes.

Judging by his music, Elias spends all day on his knees, mourning

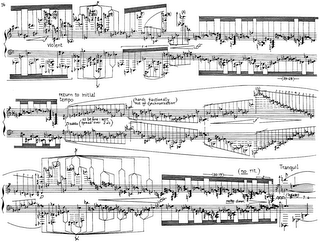

Three movements could, I suppose, just about be discerned; but you couldn’t spot Brahms or Chopin in the full-tilt cascades of notes, the scary intervals and growling reverberations, scattered with sudden pools of quiet, spidery counterpoint, or passing biffs from one of the pianist’s arms (a sample Finnissy piano score pictured below right). Saturday’s soloist Nicolas Hodges is known for his extraordinary skills in conquering the unconquerable, but even he exceeded himself by navigating this belligerently crazy score from faint and murky photocopied pages. You might as well climb Everest blindfolded.

Out of the spotlight in the Finnissy, members of the Britten Sinfonia and Saturday's unflappable conductor, Clark Rundell, showed more of their stuff in Brian Ferneyhough’s Prometheus of 1967 for wind sextet. Ferneyhough’s music usually has all the charm of a ball of barbed wire, but following Finnissy’s assault and battery the brittle, fragmentary exchanges in this early piece almost resembled the lyrical colour permutations of Webern.

No time for an interval and a comforting ice cream; instead, the concert pressed on with Nicolas Hodges back at the ivories with a more legible score, and one also more easily swallowed.

No time for an interval and a comforting ice cream; instead, the concert pressed on with Nicolas Hodges back at the ivories with a more legible score, and one also more easily swallowed.

Dedicated to Hodges, Harrison Birtwistle’s 12-minute Gigue Machine from 2011 (this was its British premiere) never overtly suggests a baroque dance, though I heard the machine of the title, hard and energetic, rattling out staccato material while more linear and legato fingerings sometimes swept through at a different speed. This wouldn’t be the first Birtwistle piece which the ear walks around as if sizing up a sculpture or gnarled rock. I’d be happy to walk round it again, especially if Hodges is playing.

I’d equally be happy to pay another visit to Brian Elias’s 17-minute vocal scena, Electra Mourns, which received a convincing world premiere performance from Rundell and the Sinfonia, mezzo-soprano Susan Bickley, and Nicholas Daniel on the cor anglais. Judging by his music, Elias spends all day on his knees, mourning. He regularly sets lamenting, death-haunted texts, preferably in Russian, though the grief embedded in Sophocles’ play Electra was obviously too juicy to pass over. Here the concert’s music audibly echoed past traditions, and achieved something otherwise scarce: direct emotional expression.

Ever ardent, Bickley’s mezzo admirably suited Sophocles’ lines featuring Electra in full flight, raging before the urn supposedly containing her brother Orestes’ ashes. Elias doubled her eloquence by mirroring her phrases with Daniel’s plangent cor anglais, backed by the Sinfonia’s sorrowing strings. Bickley was singing in ancient Greek, though we needed no translation to understand those breast-beating syllables oimoi moi. Nor did we need any signpost to grasp Sophocles’ and Elias’s double intention: acknowledging Electra’s loving feelings, while suggesting that the love has curdled into a vicious instrument of revenge. Just the bracing lesson needed for a sunny Saturday afternoon.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment