Christian McKay: Me and Orson Welles | reviews, news & interviews

Christian McKay: Me and Orson Welles

Christian McKay: Me and Orson Welles

A newcomer from Lancashire talks about his hailed reincarnation of a US film legend

"I must apologise for talking ten to the dozen," begins Christian McKay with a confidential air. "I do it when I'm nervous. I'm a rookie - I've never done this before. The stars get media training, but I thought, ‘I'm a naturally gregarious person and I'd rather be an open book'." It can't last, one thinks ruefully.

"Me" is Zac Efron, as a young man recruited by Welles to play the small role of Lucius in the play. The film's notional hero, he makes a very fair fist of his graduation from the High School Musical series that established him as a teen idol. But it's indubitably McKay who dominates the movie in the other title role, and who is its "Oscar buzz focal point," in the words of the Los Angeles Times last week.

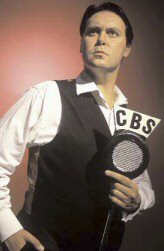

Many have tried before to play Orson (the genuine article is pictured right), with patchy success. Vincent D'Onofrio in Ed Wood (1994) was dubbed by the Canadian actor Maurice LaMarche, who has supplied an Orsonian voice-over on numerous occasions. D'Onofrio returned to Welles in the short Five Minutes, Mr Welles (2005), which he also directed. Other Orsons include Liev Schreiber in RKO 281 (1999), Angus MacFadyen in Cradle Will Rock (1999), and Danny Huston in Fade to Black (2006). Most of them have been compared to the original and found wanting. "I thought, ‘Jump in the deep end, first film, sink or swim'," declares McKay breezily. "The confidence of ignorance and all that."

Many have tried before to play Orson (the genuine article is pictured right), with patchy success. Vincent D'Onofrio in Ed Wood (1994) was dubbed by the Canadian actor Maurice LaMarche, who has supplied an Orsonian voice-over on numerous occasions. D'Onofrio returned to Welles in the short Five Minutes, Mr Welles (2005), which he also directed. Other Orsons include Liev Schreiber in RKO 281 (1999), Angus MacFadyen in Cradle Will Rock (1999), and Danny Huston in Fade to Black (2006). Most of them have been compared to the original and found wanting. "I thought, ‘Jump in the deep end, first film, sink or swim'," declares McKay breezily. "The confidence of ignorance and all that."

Spruce in suit, tie and aftershave, the Lancashire-born actor is possessed of a superabundance of charm and a booming, infectious laugh which frequently follows some funny, often highly indiscreet anecdote. "Orson is the only real-life person I've ever played," he says. "And I was fascinated with the process, although it's harder than playing fiction because you feel a terrible responsibility. It's a minefield because if you do an impression, it's death. Absolute death. That's why, when you see impersonators, they're two-minute sketches; after that it's boring. But to embody a character, as if you were playing Hamlet, you've only got yourself to use."

McKay likes to joke that he's the only actor in the world who had to lose weight to play Welles. "It's a good line, isn't it? But I was getting very big at the time. I lost two and half stone, thinking to myself that, if I looked thinner, I'd look younger," he says. He is 35 whereas the Welles of the film is 22. "But he was always an old head, years ahead of his age - with that baby face, which we've both got.

"But I didn't have his voice at all. To deepen your voice technically, you can press down on your vocal chords and lose your voice or even damage it permanently. So you have to open your throat and open your chest physically. You use the back of the mouth as a sounding board, though we don't do it really in English. It's been 18 months and I can't do it now," continues McKay, whose diction nonetheless begins to morph into Welles's fruity tones as he speaks.

"In interviews he'd twinkle at you, flirt with you: the eyes, the eyebrows, the little dimples. I had those tics and, after we'd finished the film, I kept doing all that while I was talking. Even now I can feel my face... the old man's around. And Orson laughs like a whale, Falstaffian laughing [McKay gives a great wheezing guffaw]. My own laugh was completely lost after working on it so long and trying to get it naturally. It was a strange, weird thing."

McKay has been living with Welles for a very long time. Already at drama school, fellow-students remarked on the uncanny resemblance. "My generation remembers him as the 350 pound mountain, with an ego to go with it, and so, whenever anybody said that or when the idea of playing him came up, I always said, ‘I'm not that big. Please. I've lost a pound this year!'" Orson proved harder to shed, however.

A couple of years later, fresh out of drama school, McKay was playing a eunuch in the 1999 Royal Shakespeare Company production of Antony and Cleopatra when a couple of colleagues - the director Josh Richards and writer Mark Jenkins - suggested a one-man-show about Welles. "I totally did not want to play Orson. I kept saying, ‘What about Richard Burton?' Because I can transform physically and give a flavour of [in an incredible voice] that incredible voice. What about Peter Sellers or Alec Guinness? Winston Churchill?"

But his friends persisted and, in 2004, the show, Rosebud, was the toast of Edinburgh, winning a Fringe First and another major award as well as rave reviews for McKay. He took the play round the UK and began touring with it internationally. So the big man has been good to him, I remark. "Not really," the actor replies, to my astonishment.

"I had bad times with him, really bad times. I'd been totally involved in the show, it was tailored for me, because of me and with me. I had all the books on Welles; I was doing all the research; I wanted to know everything about him. Rosebud was meant for me to make my living and then the rights were given away. I virtually had my own show taken off me, just like it happened to Orson with his films. It was a horrible, horrible experience."

Eventually the rights were clawed back and McKay (pictured left in the role on stage) was asked if he wanted to revive the show. "I said, ‘No. I've had it up to here. Orson Welles is cursed. I'll find another fat guy to play.' I was adamant. But then my wife said to me, ‘You know, you love the old man. And you worked so hard on that show. Why be defeated by circumstance and bad decision making?' And I thought ‘Well, I would quite like to play him again'."

Eventually the rights were clawed back and McKay (pictured left in the role on stage) was asked if he wanted to revive the show. "I said, ‘No. I've had it up to here. Orson Welles is cursed. I'll find another fat guy to play.' I was adamant. But then my wife said to me, ‘You know, you love the old man. And you worked so hard on that show. Why be defeated by circumstance and bad decision making?' And I thought ‘Well, I would quite like to play him again'."

Thus Rosebud blossomed again briefly off-Broadway in 2007. "The show was the success it had been in Edinburgh," he gloats. "We were playing to packed houses. In a tiny theatre, don't get me wrong. But it was my theatre. My wife produced it and then the magic happened."

In the audience one night was Linklater, who was looking for his own Orson and had been urged to catch the show. "I stood there afterwards giving him the names of Hollywood stars, thinking, ‘He's not going to cast an unknown Englishman. No way'." Even after the director had committed, the financiers demurred. "Every producer in America said, ‘Ditch the limey!' Even in London, they said, ‘Let's cast up for Orson,' and Rick said ‘No: it's Christian or I don't make the film.' I've read about people being in the right place at the right time and having diabolical, devilish, divine good luck, but this was unbelievable.

"It's my first film role and people already have mentioned the word ‘typecasting'. How can you be typecast as Orson Welles? Look at the thousands of roles he played. That would mean I get the chance to play the Scottish king, Falstaff, King Lear, Brutus, Caine, Harry Lime, Hank Quinlan in Touch of Evil. The range is extraordinary. I'd love to be typecast like that."

Rosebud spanned the whole arc of Welles' life. Linklater's film is a snapshot of the boy wonder poised on the verge of his career: overbearing, volatile, adulterous, unscrupulous, charming, mercurial, brilliant. "That's all documented fact. I didn't want to be an apologist for him." (McKay is pictured right playing Welles as Brutus in the production of Julius Caesar, which mirrored the real-life rise of totalitarianism). In only one scene, when Welles muses how everything can get taken away from you, is the mask allowed briefly to slip: "That was a very important scene to me and it was the last one we shot. I felt it was very important that he has this massive front, the bombast and the arrogance. But really he's only a 22-year-old kid putting his neck on the line, in the cauldron of New York theatre."

Rosebud spanned the whole arc of Welles' life. Linklater's film is a snapshot of the boy wonder poised on the verge of his career: overbearing, volatile, adulterous, unscrupulous, charming, mercurial, brilliant. "That's all documented fact. I didn't want to be an apologist for him." (McKay is pictured right playing Welles as Brutus in the production of Julius Caesar, which mirrored the real-life rise of totalitarianism). In only one scene, when Welles muses how everything can get taken away from you, is the mask allowed briefly to slip: "That was a very important scene to me and it was the last one we shot. I felt it was very important that he has this massive front, the bombast and the arrogance. But really he's only a 22-year-old kid putting his neck on the line, in the cauldron of New York theatre."

McKay's show was named after the central enigma of Citizen Kane: the meaning of its protagonist's dying words which, famously, the kaleidoscopic film declines finally to answer. I wondered whether he felt Welles himself was ultimately unknowable. "You can't play him if you're going to think that," the actor replies. "But he created his own legend. He wove all these tales about himself. He used to say, ‘I'm a magician.' ‘Who did you study with?' ‘Houdini!' He was on a walking holiday in Bavaria and went to a Bierkeller and a little man with a moustache was sitting next to him. He walked into the Gate Theatre in Dublin and said he was a celebrated actor from New York and they gave him the lead role. It's nonsense. He went and auditioned like everybody else, and they saw something raw in him they thought they could teach. The truth was actually a better story.

"For me, ultimately the myth destroyed him because, in the last 20 years of his life, when he was struggling to find the financing for his films, everybody believed it: that he was unreliable, that he was profligate, that he was a nightmare to work with. In fact he was the most reliable and fastest director in the world at that time." Even today the fallacy persists, McKay says: Hollywood folk have frequently remarked to him, "But Citizen Kane made no money", unaware, apparently, that it was because the media tycoon William Randolph Hearst, the prototype for Kane, used all his powers to bury the film.

Yet it survived, and how: "I've seen Kane (pictured left) a hundred times but it was re-released recently and I thought, ‘I'll go and see it again because every time you watch that movie you find something new.' I was at the BFI Southbank and the theatre was packed. In Los Angeles two days ago, I did a Q&A at a screening of Me and Orson Welles, just after a screening of Citizen Kane. The theatre there was packed too. That movie is still making a fortune," McKay thumps the table. "It's still playing all over the world. How many films from 1941 can you say that about?"

Yet it survived, and how: "I've seen Kane (pictured left) a hundred times but it was re-released recently and I thought, ‘I'll go and see it again because every time you watch that movie you find something new.' I was at the BFI Southbank and the theatre was packed. In Los Angeles two days ago, I did a Q&A at a screening of Me and Orson Welles, just after a screening of Citizen Kane. The theatre there was packed too. That movie is still making a fortune," McKay thumps the table. "It's still playing all over the world. How many films from 1941 can you say that about?"

He admits he has become something of an "Orson anorak" and possesses 96 books about the man. What surprised him the most in the course of his research? "That in America he was viewed as a failure. A fat failure. They ask, ‘What did he do after Citizen Kane?' Well, he only made another 10 masterpieces of which any average film-maker would give his right arm just to produce one. And he did it mostly independently.

"He worked in such an expensive medium that he had to sell himself by doing all those wine and dogfood and photocopier commercials [Linklater's film shows Welles already funding the production of Julius Caesar by moonlighting in radio shows]. He was making a fortune from them and putting it all into his films. For me, that is not a failure. That is a man of obstinate, utter integrity. I get a bit evangelical about it.

"I'm aware of his failings and flaws as a human being. My God, we've all got flaws, and he's a genius so he's probably got more than any of us. But all he was trying to do was to give and to entertain us, and that's a very noble and optimistic thing. The day he died [in 1985, aged 70], he'd just been on The Merv Griffin Show doing a magic trick. He went home, tired out, and had a heart attack while he was typing the next day's schedule for the film he was working on. He never stopped creating. Everybody said, ‘Oh he did nothing during the last 20 years of his life,' but look at what he was creating privately. It's staggering. A young man half his age would not be capable of such work. He flogged himself, with an unbelievable drive and ambition."

One reason why McKay is happy to talk about playing Welles with such irresistible and undiminished passion is that he knows himself to be no one-trick-pony. A professional musician, he was a chorister at Manchester Cathedral and studied at the Royal College of Music and Queensland Conservatorium before becoming a successful concert pianist. By 21, he was performing Rachmaninov's notoriously demanding Third Piano Concerto. "It was my Caesar at that age." After spending all day alone at the piano, he liked to relax with a drama troupe, acquired a taste for that too and was persuaded to apply, successfully, to RADA. But he still practises the piano daily, even on set, and hopes to record Enrique Granados' Goyescas suite next year.

His forthcoming turns include a small role in Woody Allen's next film; McKay tells a funny, self-deprecating tale about their first meeting, then adds conspiratorially, "Perhaps that's just a story for you and me because it makes me sound like an idiot." More immediately, he'll be seen in Mr Nice (opening in February), as a "crap spy" from MI6 who tries to recruit the drug dealer Howard Marks and ends up "demoted and behind a desk in a dreary office." Mindful that it's the best way to get good work, he's also writing three scripts with juicy roles for himself: as the young Winston Churchill, as an Eastern European mechanic and as a Spanish pianist-composer. So typecasting should not be on the cards.

His forthcoming turns include a small role in Woody Allen's next film; McKay tells a funny, self-deprecating tale about their first meeting, then adds conspiratorially, "Perhaps that's just a story for you and me because it makes me sound like an idiot." More immediately, he'll be seen in Mr Nice (opening in February), as a "crap spy" from MI6 who tries to recruit the drug dealer Howard Marks and ends up "demoted and behind a desk in a dreary office." Mindful that it's the best way to get good work, he's also writing three scripts with juicy roles for himself: as the young Winston Churchill, as an Eastern European mechanic and as a Spanish pianist-composer. So typecasting should not be on the cards.

As he rises to leave, McKay is still talking. There is a flood of recollections about the old Wellesians he met in the course of travelling with the show and the movie, including Arthur Anderson, Orson's original Lucius. "There was one old lady, I think she was 84, but you could tell she had been an astonishing beauty. We sat there after the show, she cried, I was holding her hand. She said, ‘You look so like him. You've done something to me.'

As he rises to leave, McKay is still talking. There is a flood of recollections about the old Wellesians he met in the course of travelling with the show and the movie, including Arthur Anderson, Orson's original Lucius. "There was one old lady, I think she was 84, but you could tell she had been an astonishing beauty. We sat there after the show, she cried, I was holding her hand. She said, ‘You look so like him. You've done something to me.'

"It slowly dawned on me that they'd had an affair while he was married to Virginia. ‘Then,' she sobbed, ‘he left me for Dolores del Rio.' I said ‘The sonuvabitch!'" McKay roars with Falstaffian laughter. Didn't his own wife play the long-suffering Virginia in Me and Orson Welles? "Yes," he says, pausing, tempted to roll out one last anecdote en route through the door. "I got into terrible trouble once because.... no, I'd better not tell you that story."

"It slowly dawned on me that they'd had an affair while he was married to Virginia. ‘Then,' she sobbed, ‘he left me for Dolores del Rio.' I said ‘The sonuvabitch!'" McKay roars with Falstaffian laughter. Didn't his own wife play the long-suffering Virginia in Me and Orson Welles? "Yes," he says, pausing, tempted to roll out one last anecdote en route through the door. "I got into terrible trouble once because.... no, I'd better not tell you that story."

Three rival Orsons (top to bottom): Vincent D'Onofrio in Five Minutes, Mr Welles, Danny Huston in Fade to Black, Angus Macfadyen in Cradle Will Rock.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...

...