The Wolverine | reviews, news & interviews

The Wolverine

The Wolverine

The X-Man goes to Japan, but stays a mediocre superhero

Wolverine is a second-division, third-generation Marvel superhero, and for all the care devoted to his sixth cinema outing, he remains the problem here. First introduced in 1974, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby – comics’ Lennon and McCartney – were no longer on hand to conceive this metal-clawed lunk with the adolescently resonant weaknesses they gave Spider-man and the rest. Instead, Wolverine had over-wrought, tin-eared Chris Claremont to chronicle his key years as the star turn in the X-Men, a firm fan favourite who never touched the general public.

This second attempt at a solo film away from the X-Men franchise is based on a 1980s mini-series by Claremont and Frank Miller, which landed Wolverine in Japan, and Miller’s favoured milieu of samurai, ninjas, codes of honour and gut-opening swordplay. The capable, stylish director James Mangold exploits this setting for all its worth, aiming for a “fever dream” of modern Japan, mixing ancient warriors and industrialists, and bullet-training from Tokyo to the rustic, lazing south.

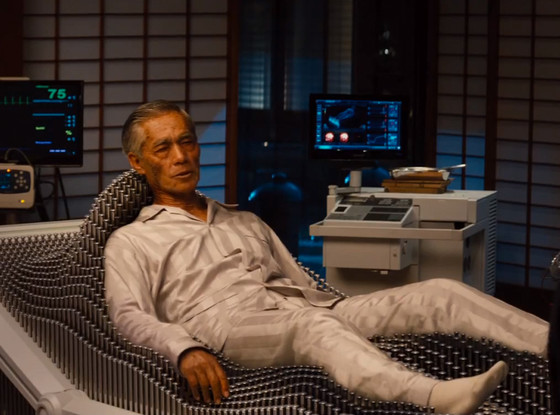

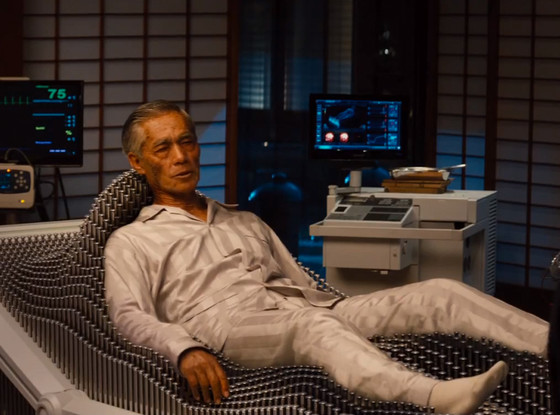

He opens with the Atom bomb blasting Nagasaki, where the immortal, indestructible Wolverine (Hugh Jackman) saves a young Japanese soldier. In the present day, that soldier has become dying industrialist Lord Yashida (Haruhiko Yamanouchi, pictured right). Drawing a drifting Wolverine to his death-bed, he tells him that the immortality which has come to seem like a curse can be extracted and transferred to another. After a mass Yakuza assault on Yashida’s funeral, Wolverine rescues the industrialist’s grand-daughter and heir Mariko (Tao Okamoto, pictured below with Jackman), going on the run together across Japan. Finding his indestructibility has indeed been removed, our hero is bloodied, wounded, vulnerable: about as interesting as he’s ever been.

He opens with the Atom bomb blasting Nagasaki, where the immortal, indestructible Wolverine (Hugh Jackman) saves a young Japanese soldier. In the present day, that soldier has become dying industrialist Lord Yashida (Haruhiko Yamanouchi, pictured right). Drawing a drifting Wolverine to his death-bed, he tells him that the immortality which has come to seem like a curse can be extracted and transferred to another. After a mass Yakuza assault on Yashida’s funeral, Wolverine rescues the industrialist’s grand-daughter and heir Mariko (Tao Okamoto, pictured below with Jackman), going on the run together across Japan. Finding his indestructibility has indeed been removed, our hero is bloodied, wounded, vulnerable: about as interesting as he’s ever been.

Mangold is responsible for surprising and entertaining turns in the careers of Sylvester Stallone (Cop Land), Angelina Jolie (Girl, Interrupted), Russell Crowe (3.10 to Yuma), Joaquin Phoenix (Walk the Line) and John Cusack (Identity), and has worked with Hugh Jackman before, on the Meg Ryan romance Kate and Leopold. He brings out his star’s easy, straightforward decency and muscular charisma, and sets him to work in what for much of its more than two hours is a modern film noir, with a haunted knight errant as its hero. Okamoto is also excellent, woefully under-written but communicating great depth, as does Yamanouchi, fearsomely steely and calculating even as his character lies dying. There are some extraordinary images too, such as Wolverine’s harpooning by dozens of ninja arrows, straining but reeled in to a backdrop of mountain snow. The moment when all this good work unravels is easy to spot: it’s when Wolverine regains his indestructibility. When a hero instantly heals after his opponent hits his heart fair and square with a sword, you start to side with the hapless bad guys. The final reel is schematic and battle-heavy, full of obvious revelations and the over-heated, unconvincing pulpiness of a typical 1970s Marvel comic. Basically, it becomes another Wolverine yarn, and the energy and talent expended to find something worthwhile in that falls exhausted to the floor. It’s enjoyable, even memorable. But comic-book lead can’t be turned into gold.

The moment when all this good work unravels is easy to spot: it’s when Wolverine regains his indestructibility. When a hero instantly heals after his opponent hits his heart fair and square with a sword, you start to side with the hapless bad guys. The final reel is schematic and battle-heavy, full of obvious revelations and the over-heated, unconvincing pulpiness of a typical 1970s Marvel comic. Basically, it becomes another Wolverine yarn, and the energy and talent expended to find something worthwhile in that falls exhausted to the floor. It’s enjoyable, even memorable. But comic-book lead can’t be turned into gold.

Overleaf: watch the trailer to The Wolverine

Wolverine is a second-division, third-generation Marvel superhero, and for all the care devoted to his sixth cinema outing, he remains the problem here. First introduced in 1974, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby – comics’ Lennon and McCartney – were no longer on hand to conceive this metal-clawed lunk with the adolescently resonant weaknesses they gave Spider-man and the rest. Instead, Wolverine had over-wrought, tin-eared Chris Claremont to chronicle his key years as the star turn in the X-Men, a firm fan favourite who never touched the general public.

This second attempt at a solo film away from the X-Men franchise is based on a 1980s mini-series by Claremont and Frank Miller, which landed Wolverine in Japan, and Miller’s favoured milieu of samurai, ninjas, codes of honour and gut-opening swordplay. The capable, stylish director James Mangold exploits this setting for all its worth, aiming for a “fever dream” of modern Japan, mixing ancient warriors and industrialists, and bullet-training from Tokyo to the rustic, lazing south.

He opens with the Atom bomb blasting Nagasaki, where the immortal, indestructible Wolverine (Hugh Jackman) saves a young Japanese soldier. In the present day, that soldier has become dying industrialist Lord Yashida (Haruhiko Yamanouchi, pictured right). Drawing a drifting Wolverine to his death-bed, he tells him that the immortality which has come to seem like a curse can be extracted and transferred to another. After a mass Yakuza assault on Yashida’s funeral, Wolverine rescues the industrialist’s grand-daughter and heir Mariko (Tao Okamoto, pictured below with Jackman), going on the run together across Japan. Finding his indestructibility has indeed been removed, our hero is bloodied, wounded, vulnerable: about as interesting as he’s ever been.

He opens with the Atom bomb blasting Nagasaki, where the immortal, indestructible Wolverine (Hugh Jackman) saves a young Japanese soldier. In the present day, that soldier has become dying industrialist Lord Yashida (Haruhiko Yamanouchi, pictured right). Drawing a drifting Wolverine to his death-bed, he tells him that the immortality which has come to seem like a curse can be extracted and transferred to another. After a mass Yakuza assault on Yashida’s funeral, Wolverine rescues the industrialist’s grand-daughter and heir Mariko (Tao Okamoto, pictured below with Jackman), going on the run together across Japan. Finding his indestructibility has indeed been removed, our hero is bloodied, wounded, vulnerable: about as interesting as he’s ever been.

Mangold is responsible for surprising and entertaining turns in the careers of Sylvester Stallone (Cop Land), Angelina Jolie (Girl, Interrupted), Russell Crowe (3.10 to Yuma), Joaquin Phoenix (Walk the Line) and John Cusack (Identity), and has worked with Hugh Jackman before, on the Meg Ryan romance Kate and Leopold. He brings out his star’s easy, straightforward decency and muscular charisma, and sets him to work in what for much of its more than two hours is a modern film noir, with a haunted knight errant as its hero. Okamoto is also excellent, woefully under-written but communicating great depth, as does Yamanouchi, fearsomely steely and calculating even as his character lies dying. There are some extraordinary images too, such as Wolverine’s harpooning by dozens of ninja arrows, straining but reeled in to a backdrop of mountain snow. The moment when all this good work unravels is easy to spot: it’s when Wolverine regains his indestructibility. When a hero instantly heals after his opponent hits his heart fair and square with a sword, you start to side with the hapless bad guys. The final reel is schematic and battle-heavy, full of obvious revelations and the over-heated, unconvincing pulpiness of a typical 1970s Marvel comic. Basically, it becomes another Wolverine yarn, and the energy and talent expended to find something worthwhile in that falls exhausted to the floor. It’s enjoyable, even memorable. But comic-book lead can’t be turned into gold.

The moment when all this good work unravels is easy to spot: it’s when Wolverine regains his indestructibility. When a hero instantly heals after his opponent hits his heart fair and square with a sword, you start to side with the hapless bad guys. The final reel is schematic and battle-heavy, full of obvious revelations and the over-heated, unconvincing pulpiness of a typical 1970s Marvel comic. Basically, it becomes another Wolverine yarn, and the energy and talent expended to find something worthwhile in that falls exhausted to the floor. It’s enjoyable, even memorable. But comic-book lead can’t be turned into gold.

Overleaf: watch the trailer to The Wolverine

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Add comment