Immigration riots and the hand of Shakespeare | reviews, news & interviews

Immigration riots and the hand of Shakespeare

Immigration riots and the hand of Shakespeare

Extract from the RSC's new volume of Shakespeare's collaborations introduces 'Sir Thomas More'

It begins on the street, nastily. An immigrant has got his hands on an English woman. Trouble is brewing. Then there is a dispute about money, involving a “Lombard” – the identification originally applied to immigrants from Lombardy in northern Italy, famous for its banking, but it had gradually become a term of abuse for all foreigners engaged in trade or banking, a word bandied around in the same way as “Jew”.

Before long, London is burning. Order has broken down and the people have taken the law into their own hands. The mob mentality calls it rough justice… On May Day 1517 London witnessed the worst race riot of the age. A mob of over a thousand angry young men and women gathered near St Paul’s and tore through the City, destroying property and assaulting anyone who stood in their path. Most were poor labourers or apprentices. They broke into Newgate Prison, freeing inmates who had been detained for attacking foreigners. The riot was brought to a temporary halt when the charismatic Under-sheriff of London, Sir Thomas More, confronted the crowd. But soon they went on the rampage again, trashing foreign-owned small businesses and demanding the deportation of immigrants.

In the final years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, Shakespeare dramatised the encounter between More and the crowd as his contribution to this multi-authored comi-tragedy, which has a complicated history of collaboration and revision. He gave More a powerful speech asking the crowd to put themselves into the position of the outsider, to imagine what it would be like to be “the wretched strangers, / Their babies at their backs, with their poor luggage / Plodding to th’ports and coasts for transportation”. But even with More’s subsequent lines about the king as God’s representative on earth and the need for the people to show absolute obedience, the subject matter was too hot to handle.

The role of More is one of the largest in the entire repertoire of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama

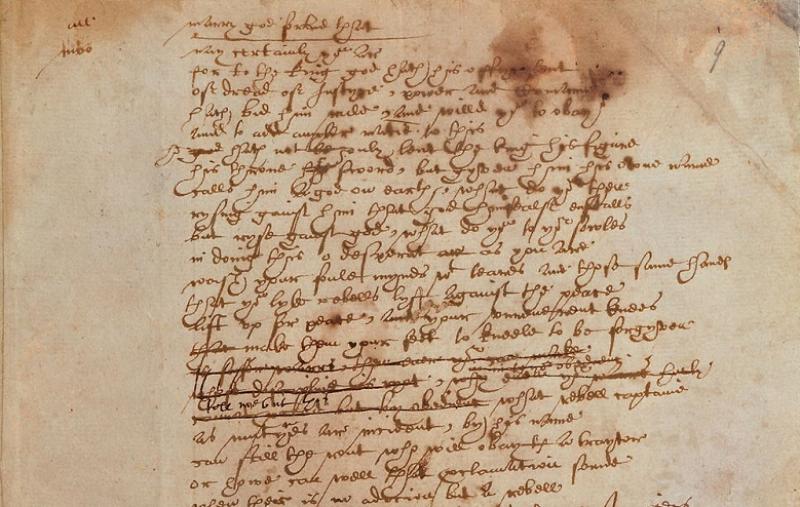

The play had already been refused permission for staging, unless major revisions were undertaken: “Leave out the insurrection wholly”, wrote Master of the Revels Edmund Tilney on the manuscript, “with the cause thereof, and begin with Sir Thomas More at the Mayor’s sessions with a report afterwards of his good service done, being Sheriff of London, upon a mutiny against the Lombards only by a short report and not otherwise, at your own peril.” As far as we know, even with the revisions, the play was never staged. Shakespeare’s scene remained unknown for two centuries. By good fortune, the prompter’s master-copy – known as the “book” – was preserved and later rediscovered. The inserted scene, in the original holograph that scholars call “Hand D”, is the only surviving example of a working manuscript in Shakespeare’s hand. Now held in the British Library in London, these three pages are among the most precious literary documents in the world.

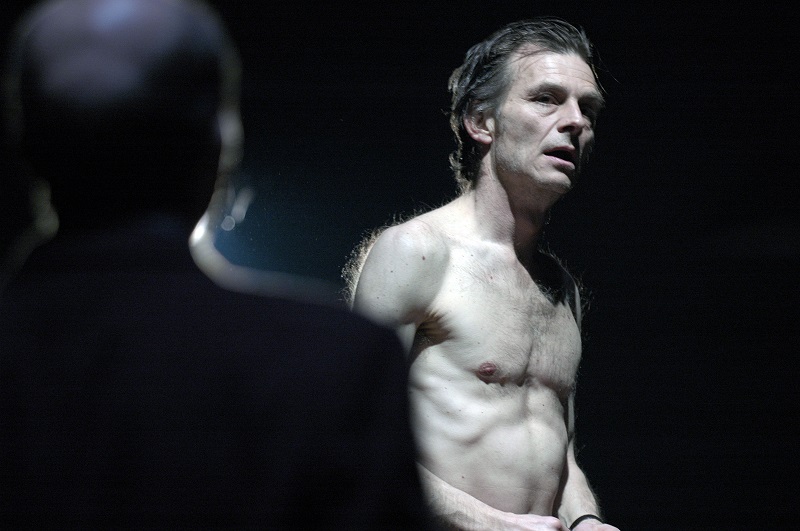

One can readily understand why Shakespeareans often look at the scene in isolation. But in approaching Shakespeare as collaborator, we must place it in context. For one thing, it fits seamlessly into the play. For another, it is probably not Shakespeare’s only intervention in the script. And besides, taken as a whole, the play is a riveting piece of theatre, as has been seen in a number of modern revivals – at the Nottingham Playhouse in 1964 with a young Ian McKellen in the title role, in Bristol and London in 1980 by a company called the Poor Players, and in 2005 on the stage of the Swan Theatre in Stratford upon-Avon.

The role of More, six times the length of the second-biggest part, is one of the largest in the entire repertoire of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. It calls for an actor of great versatility: we see him commanding both a crowd and a council chamber, meditating in soliloquy and taking rapid action, philosophising and philanthropising. He is a prankster, a Christian and a voice of reason, truly the wisest fool in Christendom (though it is disappointing that his encounter with his great fellow philosopher and wit, Erasmus of Rotterdam, comes to so little). If, as seems likely, the Shakespearean intervention in the script was intended for a production by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, then one can see why they wanted to stage the play: it would have been a magnificent showcase for their lead tragedian and Shakespeare’s intimate friend Richard Burbage.

As a tragedy, Sir Thomas More belongs beside the Chamberlain’s Men’s Thomas Lord Cromwell and Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Henry VIII as the story of the rise and fall of a royal counsellor in the turbulent time of the English Reformation. More ascends from Sheriff of London to Lord Chancellor, but falls from the king’s favour when he refuses to participate in the process of enacting the break from Rome. It’s a satisfying arc: we get a full ascendancy, a brief period of power and favour, and then a slow descent to the execution. The moments of More’s career chosen to illustrate this movement are well chosen, oscillating between his most public appearances (the May Day riots, his execution) and private ones (his conversation with Erasmus, his defence of his position to his family). In balancing character and plot, the dramatists create a coherent portrait that, ultimately, goes to show the fickleness of favour and the cost of piety. In the closing scenes, we see him preparing for death with dignity and grace. Whereas the usual scenario in such dramas places the condemned man alone in his cell, sometimes in conversation with his keeper, here we also witness More’s farewell to his family. He is seen as a husband and parent, not just a holy man and a politician.

As a tragedy, Sir Thomas More belongs beside the Chamberlain’s Men’s Thomas Lord Cromwell and Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Henry VIII as the story of the rise and fall of a royal counsellor in the turbulent time of the English Reformation. More ascends from Sheriff of London to Lord Chancellor, but falls from the king’s favour when he refuses to participate in the process of enacting the break from Rome. It’s a satisfying arc: we get a full ascendancy, a brief period of power and favour, and then a slow descent to the execution. The moments of More’s career chosen to illustrate this movement are well chosen, oscillating between his most public appearances (the May Day riots, his execution) and private ones (his conversation with Erasmus, his defence of his position to his family). In balancing character and plot, the dramatists create a coherent portrait that, ultimately, goes to show the fickleness of favour and the cost of piety. In the closing scenes, we see him preparing for death with dignity and grace. Whereas the usual scenario in such dramas places the condemned man alone in his cell, sometimes in conversation with his keeper, here we also witness More’s farewell to his family. He is seen as a husband and parent, not just a holy man and a politician.

It may partly have been because the role of More is so demanding that the dramatists introduced a play-within-the play halfway through, allowing him to rest a little and become a passive spectator instead of a continually active player. At the same time, The Marriage of Wit and Wisdom serves as an enactment of More’s own virtues: he was revered for precisely this combination of qualities. Every bit as much as “Pyramus and Thisbe” in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “The Mousetrap” in Hamlet and Hieronimo’s production of “Soliman and Perseda” in The Spanish Tragedy, this interlude provides fascinating insights into the stagecraft of early touring players. Luggins has run to get a beard, one boy-actor is down to play three parts, and Wit is required to improvise to match More’s interruptions. In a very Shakespearean way, the inclusion of a play-within-the-play is a reminder that we are all players on this great stage of the world. As More puts it in the very final scene, “my offence to his highness makes me of a state pleader a stage player (though I am old, and have a bad voice) to act this last scene of my tragedy”.

Nigel Cooke as Sir Thomas More in Thomas More, Swan Theatre, 2005. (Photo by Hugo Glendinning © Royal Shakespeare Company)

Nigel Cooke as Sir Thomas More in Thomas More, Swan Theatre, 2005. (Photo by Hugo Glendinning © Royal Shakespeare Company)

As well as creating a genuine tragic hero out of Sir Thomas More, the play presents history from the ground up. The ordinary citizens are more fully realized and individualized than in most Elizabethan dramas of this kind. Doll Williamson is as good a part as Doll Tearsheet in Henry IV Part 2. There are touches of uniquely Shakespearean genius in his contribution: Lincoln manages to turn even vegetables into a form of racial abuse (“They bring in strange roots, which is merely to the undoing of poor prentices, for what’s a sorry parsnip to a good heart?”), while Doll gives an instantaneous back-story to the people’s affection for More by recalling that “a keeps a plentiful shrievalty, and a made my brother Arthur Watchins sergeant Safe’s yeoman”. But in Munday’s original script the bit parts such as Faulkner, Randall and Lifter are also sympathetically drawn. Even the nameless Warders and Woman of the final act are surprisingly fleshed out.

Equally, even before Shakespeare’s intervention, the riot scenes of the first two acts are a source of genuine excitement. Picking up on similar scenes in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 2 (the Jack Cade sequence) and the anonymous play of Jack Straw, they allow rioting citizens to both air their grievances and condemn themselves with their foolishness. Lincoln is a complicated anti-hero, seemingly noble at first, then succumbing to more base demands, before being allowed a fine gallows speech. The bustle of these scenes is expertly drawn and this gives all the more impact to More’s great oration, with its balance between empathy for the outsider and the need to respect the rule of law.

The language of More’s address to the crowd towers over the play. No one but Shakespeare could have invented such images as “in ruff of your opinions clothed”, a metaphor that is utterly characteristic in itself clothing an abstract idea in material dress, or “For other ruffians ... / Would shark on you, and men like ravenous fishes / Would feed on one another”, with its – again, deeply characteristic – device of creating poetic energy by turning a noun into a verb. But there is some beautiful poetry elsewhere in the play, particularly in More’s reflections on his own rise and fall. The soliloquy at the pivotal point in the third act (“It is in heaven that I am thus and thus”), though written in the hand of the playhouse scribe, has all the hallmarks of a further Shakespearean addition, probably written in for the sake of strengthening Burbage’s part still further. “Prerogative and tithe of knees” and “the smooth and dexter way” are fine examples of Shakespeare’s favoured doubling device known in rhetoric as hendiadysis, while a phrase such as “humble bench of birth”, together with images of blood turned to corruption and of “serpents’ natures”, has the feel of mature Shakespeare, as does the climactic image-cluster that winds together several terms out of the language of weaving (“thread ... spun ... / A bottom greatly wound up greatly undone” – a “bottom” is a ball of thread or the clew on which the thread is wound, from which Shakespeare got the name for Bottom the weaver in A Midsummer Night’s Dream).

The exact circumstances in which Shakespeare made his contribution to Sir Thomas More will never be known, though scholars now lean strongly to the view that he did so when at the height of his powers in the early 1600s, not in a prior stage of his career, as was once supposed. But, whatever the date and context, an overwhelming body of internal evidence, in the form of unique marks of orthography, spelling, vocabulary and literary technique, attests that the so-called “Hand D” in the manuscript is truly his. This is Shakespeare in the act of composition, writing rapidly, occasionally changing a word or scratching out a line, mining his capacious imagination and minting his incomparable poetic imagery. But it is also Shakespeare the collaborator, building on the work of other dramatists and contributing to a magnificent team effort.

- William Shakespeare and Others: Collaborative Plays (The RSC Shakespeare) edited by Professor Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen is published by Palgrave Macmillan (£25)

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Beautiful Future is Coming / She's Behind You

A deft, epoch-straddling climate six-hander and a celebration (and take-down) of the pantomime dame at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Beautiful Future is Coming / She's Behind You

A deft, epoch-straddling climate six-hander and a celebration (and take-down) of the pantomime dame at the Traverse Theatre

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Comments

These eminent scholars have

In other words you didn't