A Will of My Own | reviews, news & interviews

A Will of My Own

A Will of My Own

On Shakespeare's 450th birthday, Steven Berkoff recalls his eventful life with the Bard

I hardly knew anything about Shakespeare as a schoolboy and it was only when attending my first acting classes, when we sallow and uncouth students were required to do a speech each week to be tested on, that I had my first awakenings. At the very first I found the dense text too complex and remote for my taste, but persevered, swallowed the language in great chunks and then heaved it out. But from the outset I felt that something had bit.

I became gradually more and more enamoured of the Bard. It seemed as if he was thrusting more meaning and diversity in to nearly every line and the result of this is that the complexity of existence is slowly peeled away like the fine skin of an onion. He stretches the very meaning of communication, unravelling it, examining it from every spectrum, from every angle, and in doing so informs us humble readers that we are so capable of revealing the limitless depths of human feeling. So as an actor, how can you not be stretched to your limits, refined in your thought processes, alerted to greater and more bizarre worlds? What makes Shakespeare also so very seductive is that he bares the human soul, strips it down to its essence, makes us walk naked and exposed. So when Hamlet is questioned by his mother Gertrude and she casually uses the word "seems"… To describe his lot, Hamlet answers as if to paint a picture of not only what "seems" is but what he is, as if speaking for a battalion of young men. "Seems, madam? Nay it is, I know not seems."

Tis not alone my inky cloak good mother,

Nor customary suits of solemn black,

No nor the windy suspiration of forced breathe.

No nor the fruitful river in the eye

That can denote me

For I have within that passes show

These but the trappings and the suits of woe.

Shakespeare paints pictures as no other playwright before or since the Greeks.

We so easily see Hamlet and feel him and know him and almost smell him. Grief has never been so finely balanced. Passion never so intensely expressed as Romeo’s heart-rending descriptions of Juliet. Sarcasm mixed with utter contempt never so brilliantly expressed as by Coriolanus’s invective to the common self-seeking mob. Utter maniacal jealousy never so coruscatingly expressed than in Othello’s bitter rages and frustration. Lyricism and sexual innuendo never so brilliantly described as by Oberon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Low scheming cunning never so boldly and flagrantly expressed as by Iago as he slowly poisons the vulnerable mind of his master the Moor. A plea for simple understanding and moral probing never better said than by Shylock in his speech pleading for the sentence and humanity of the Jew. The all-consuming horror of ambition fuelled by the most dastardly crime as in Macbeth, and then what description can ever match the sorrowful and sickening guilt of his poor wife Lady Macbeth as she desperately tries to wash her hand raw from the spots of blood that never can be erased. And so it goes on in play after play as Shakespeare seems actually to define the very elements of the curious mess that is a human being, as a surgeon probes the internal organs of the body.

His characters explore who we are as players

Actors love nothing better than to express themselves via the characters they play and few characters are as defined as Shakespeare’s. His characters at the same time explore who we are as players. Consequently we are allowed to mine every facet of our most wonderfully complex being. The better the actor the more he will be refined, sculptured and articulated when he is performing Shakespeare. He will be purged, scorched and strengthened by the task. When I was a mere apprentice in the dramatic arts I nevertheless knew that great actors are only truly great when they have played the great tragedies since they shape what kind of actor you are. In playing Shakespeare you become more than a mere travelling player, you might be entering a priesthood. The text is your sermon and few writers have touched upon the principles that keep a nation morally fit and Shakespeare has more examples of ethical behaviour and the honour of self-sacrifice than the Bible, both Old Testament and New.

In my youth I was lucky to have witnessed some of the high priests of Shakespeare. I could never forget the strikingly theatrical performances of Alec McCowen: his Mercutio was everything that acting could ever be in Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet at the Old Vic. McCowen was an illuminator of the Bard as was Olivier whose Othello I had the rare privilege to see at the first night in Chichester. It was a performance beyond anything I had witnessed in my life. So intense and profound was it that at the curtain not one member of the packed house felt even bold enough to clap. I also saw Paul Scofield’s dynamic and heart-rending Lear. These were performances that outlined the parameters of great acting and I was enamoured and so proud that I had chosen this profession that just might, perhaps, with some luck and practice, lead me one day down that same stretch of land.

Alas, it was not to be and although I auditioned for the directors of the day, I seemed never to be what they were looking for. However I was not going to allow them to decide my fate. I had to do it myself. I would play Macbeth with my own actors in my own company. With my stalwart and clever colleague Pip Donaghy we auditioned and slowly selected our young group of wonderfully enthusiastic players. After many months of workshops and rehearsals, at last we were ready to show the fruits of our work. Alas, the critics lambasted us. This did not deter us but only increased our zeal. Years later we did Hamlet with myself as Hamlet and directing and again with such an able bunch of performers. This time after our premiere at the Edinburgh festival we toured Europe, being rewarded with resounding reviews in every town we played. Until we came to London where we again were shot down in flames. This deterred us even less since now we had a European connection, but alas Shakespeare had to take a rest for a while while I concentrated on plays we could afford to rehearse.

Alas, it was not to be and although I auditioned for the directors of the day, I seemed never to be what they were looking for. However I was not going to allow them to decide my fate. I had to do it myself. I would play Macbeth with my own actors in my own company. With my stalwart and clever colleague Pip Donaghy we auditioned and slowly selected our young group of wonderfully enthusiastic players. After many months of workshops and rehearsals, at last we were ready to show the fruits of our work. Alas, the critics lambasted us. This did not deter us but only increased our zeal. Years later we did Hamlet with myself as Hamlet and directing and again with such an able bunch of performers. This time after our premiere at the Edinburgh festival we toured Europe, being rewarded with resounding reviews in every town we played. Until we came to London where we again were shot down in flames. This deterred us even less since now we had a European connection, but alas Shakespeare had to take a rest for a while while I concentrated on plays we could afford to rehearse.

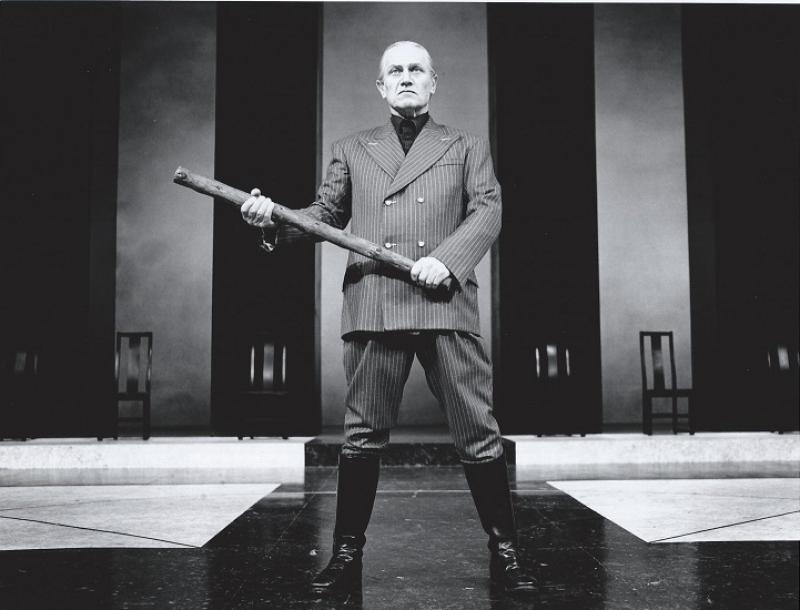

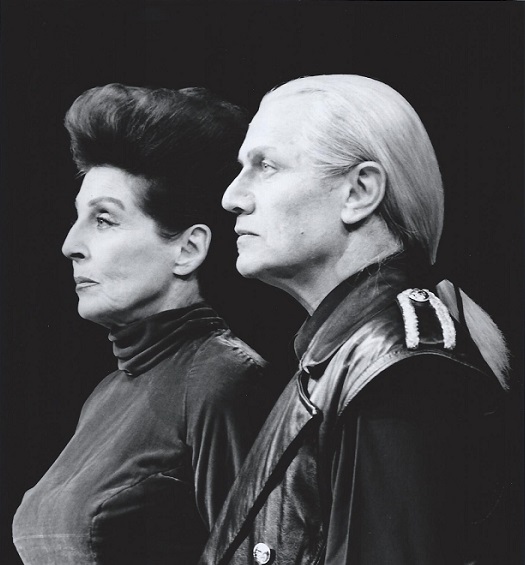

Eventually my first invitation to direct Shakespeare in Britain came from Jude Kelly at West Yorkshire Playhouse where we staged Coriolanus (pictured above, Berkoff with Faith Brook). Again with me playing the title role. This we eventually took to the Mermaid and this time the reviews were highly positive. The critics had changed. This we took to Israel, and Tokyo. Eventually just in a desire to explore Shakespeare in a one-man show I devised Shakespeare’s Villains, playing all my favourite bad guys and a couple of bad girls. This show I have performed in Australia, Los Angeles, New York, Rio, São Paulo, Florence, Rome, Milan, Barcelona, Jerusalem, Oregon, Edinburgh, Oxford, Brighton etc. I was never invited to places like the RSC which at one time in my youth was an all-consuming dream. However I did what I could myself and the Bard has always supported me and I hope will continue to do so.

© Steven Berkoff 2014

- Steven Berkoff's Richard II in New York (Publishnation) is available as a Kindle book on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment